Ayesha Perveen, Virtual University of Pakistan

Perveen, A. (2018). Role of MOOCs in Pakistani English teachers’ professional development. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(1), 33-54. https://doi.org/10.37237/090104

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

The paper takes up one of the least researched areas in Pakistan i.e. the role of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) for professional development in general and the capacity building of English teachers in particular. Although MOOCs are getting popular in Pakistan, the majority is still unaware of the concept especially those who teach in traditional face-to-face mode. As many second language University teachers have not attended any MOOCs, convenience sampling was used for data collection. Only 32 respondents completed the questionnaire. The reliability of the questionnaire on Cronbach alpha was 0.83. The results show that the number of Pakistani English teachers responding to the survey who attended MOOCs either partially or completely, was very low. Therefore, of course, the number of MOOCs attended by each was also very low. However, whoever attended and whichever MOOCs were attended, the teachers found them quite beneficial for their overall professional development, be it language improvement or teaching skill set development. The researcher recommends the use of MOOCs in classrooms which is only possible if more English Language Teaching MOOCs are available and teachers attend a variety of MOOCs. The researcher also highlights the need to develop Pakistani MOOCs with a national flavour.

Key words: MOOCs, teachers, professional development, capacity building, second language acquisition

A Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) is an online course available for a large number of participants and is open for all without any specific enrolment procedure or fee requirements. However, in order to obtain a verified certificate, participants need to pay in some instances like Coursera MOOCs which was not the case in the past as MOOCs began as an overall free education initiative. However, a parallel free version without a certificate still exists. In spite of some developments that have taken place so far, MOOCs are a relatively new phenomenon in online education with only nine years of history. With the first MOOC initiation in 2008, they became more popular from 2012 onwards. The New York Times declared 2012 as the MOOC year (Pappano, 2012). MOOCs provide the opportunity for free education to anyone anywhere in the world. Beginning with the initial endeavours with Connectivist MOOCs known as CMOOCs, Harvard and MIT X MOOCs have also been established. Whereas CMOOCs are connectivist in nature, providing students with opportunities to connect with each other and construct knowledge themselves, X MOOCs are offered in a traditional way with video lectures, assessment activities and even discussion fora built in one Learning Management System (LMS) type platform. Recently with the expansion in the platforms offering MOOCs, special consideration is being rendered to the development of an improved instructional design for MOOCs. Although MOOCs were originally aimed to support those students who do not afford formal university education, mostly professionals made use of the opportunity. A recent study by Seaton, Coleman, Daries, & Chuang (2014) contends that most of the X MOOCs participants are teachers.

Teachers’ professional development is one of the most important elements for achieving effective teaching-learning processes. It not only helps teachers in their capacity building and improves their teaching practices (Gore & Ladwig, 2006) but also facilitates the learning process of students (Borko, 2004) as teachers should be reflective practitioners (Schön, 1983). The changing dimensions of education have also led researchers talk about the opportunities of online professional development in comparison with face-to-face traditional practices. Killion and Williams (2009) find the opportunities of online professional development as having great potential for improving teaching and learning processes. Brooks and Gibson (2012) consider online teacher professional development (OTPD) as more personally relevant, meaningful and engaging to teachers because of four reasons. First OTPD provides teachers flexibility due to the choice of opting in and opting out of their learning experience; second, it provides the technological facility of being available anywhere, anytime; third, OTPD facilitates connections between teachers, professionals and researchers; and fourth, OTPD provides a reflexive space (Brooks & Gibson, 2012).

The concept of life-long learning which is becoming more popular with MOOCs has always existed in the case of teachers as they need to keep improving and gaining more and more know-how or meta learning about ways of Continuing Professional Development (CPD). CPD is an intensive form of PD as it refers to a personal commitment of professionals to continue improving their professional skills over a lifetime. This helps them to improve and broaden their knowledge, polish their skills and enhance their abilities through training. For this personal commitment they have to be on a lookout for training opportunities in the form of workshops, seminars, conferences, short courses, etc. An English language teacher should adapt him/herself to the latest development and challenges in the domain by reading, collaborating, adapting, researching, joining groups, going to seminars and workshops. For this purpose, however, there are not many opportunities for CPD in developing countries. If there are, they involve a lot of competition and travelling. For CPD, almost all institutions around the world take special measures to keep their staff updated with the latest developments in their respective domains. In English language and literature teaching, whereas few institutions may take good care of this aspect, mostly such opportunities are unavailable, expensive or not well publicized. Therefore, teachers have to seek them out and paying a good deal of money for them. Even in case of highly ambitious teachers, within the country, no foreign exposure is available in English teaching scenario in Pakistan. How to provide free and effective CPD opportunities to teachers has remained challenging. Some measures by the Government of Pakistan or foreign agencies have been taken but they remain insufficient. For example, Higher Education Commission (HEC) provides trainings to University and College teachers under the banner of English Language Teaching Reforms (ELTR) and Directorate of Staff Development (DSD) facilitates overall training for all teachers. Foreign aided institutions like British Council and US Embassy also facilitate English Language Teachers with training opportunities but many teachers are not familiar of them and they remain restricted to a few especially in main cities. Although HEC has contributed a lot to the CPD of English Teachers in Pakistan in all provinces, but it is mostly restricted to universities and colleges. Still a lot more is required.

In this state of affairs, information and communication technologies seem to be changing the global scenario of world education by moving beyond traditional face to face classrooms and providing access to online education (Perveen, 2015). Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) and Mobile Assisted Language Learning (MALL) or Technology Mediated Language Learning can be of great help if teachers are aware of the new technologies and after professional development, train their students too. However, educational endeavours like MOOCs seem to offer great opportunities for all teachers, be they in cities or far flung areas. They allow teachers access to CPD at their homes via a computer or mobile and an internet connection.

MOOCs can help with CPD because they are convenient, may give credit to teachers, improve their teaching by giving them exposure to various teaching styles, help them to use technology in their classrooms, and above all keep them aware of the latest trends and developments in their domains (Hicks, 2015). They can be attractive for teachers because they are free, flexible, adaptable, ongoing, can be used as classroom resources, and therefore, motivate teachers (Marquis, 2013). The teachers in need of CPD can be divided into three groups: 1. those who already have teaching qualification but need to keep pace with latest developments, 2. those who do not have a teaching qualification and need to learn it 3. those who need a reorientation due to change of syllabus etc. When MOOCs can be considered as a platform for CPD, these differences should be kept in mind (Fyle, 2013). CPD should be socially and culturally oriented and should inculcate a culture of sharing amongst teachers through a community centred approach, so that teachers can reflect upon their beliefs and practices (Barab, Makinster, Moore, & Cunningham, 2001). Gaible and Burns (2005) divide CPD into three types: 1, standardized, 2. site-based, 3, self-directed. Standardized CPD refers to training based approach by making teachers aware of the instructional design either through a face-to-face or online mode. Site based CPD mostly takes place in schools and colleges or training institutions. The facilitators or trainers train teachers about pedagogy in this case. Technology can be a part of this, however. Self-directed CPD refers to teachers’ personal efforts to satisfy their self-specified professional goals and is based on individual needs (Gaible & Burns, 2005). MOOCs facilitate the first and the third one but the third all the more as they are self-directed. Self-directed education needs awareness on the part of teachers and that is directly related to motivation.

However, implementation is not as simple as it sounds because awareness about MOOCs in all parts of a country like Pakistan and the motivation on the part of the teachers to attend MOOCs till completion needs a good deal of research. Nevertheless, it is a trending concept and is being introduced in Pakistan. For example, The Regional English Language Office (RELO) of the U.S. Embassy, Islamabad arranged a five-day professional development workshop, English for Specific Purposes MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) Camp in Islamabad (Quaid-e-Azam University) on February 20-24, 2017. Ball State University faculty facilitated training for 40 Pakistani educators on facilitating MOOC study groups and integrating MOOC content into traditional classes, as well as on teaching autonomous learning strategies to students to promote success in online learning environments. The following five Coursera MOOCs were highlighted with a specific emphasis on English for Career Development by this training:

- English for Business and Development

- English for Journalism

- English for Career Development

- English for Media Literacy

- English for STEM Fields

This training combined face-to-face training with online engagement i.e., blended learning to support educators for implementing MOOC-related activities in their home institutions and did not focus on online training entirely. However, this is a rare example and awareness about MOOCs leading to availing their full benefit has still to go a long way.

Although MOOCs can be considered a disruptive trend in higher education, how much they have been beneficial in professional development in particular domains is little researched. In particular, one finds few research studies on professional teacher development in general and ELT professional development in particular. One of the potential benefits can be that teachers do not have to travel which may save time. Other benefits include free access, saving time from lengthy processes and access to latest international developments in teaching and contribution to research and knowledge. MOOCs can introduce teachers to the latest international teaching trends for free and with no entry requirements. However, all these possibilities need to be researched in various countries separately. It is important to explore teachers’ awareness of MOOCs, their attitudes towards them and their opinions about the benefits which MOOCs can render especially with reference to their potential about teacher professional development. It is also important to mention that not many platforms have offered professional development or teacher training courses for ELT teachers. Initially, Coursera offered a few courses on English language and literature followed by Edx and then FutureLearn also took the initiative.

This study is an attempt at exploring the impact of MOOCs on English language and literature teachers in Pakistan both from language improvement point of view and indirectly learning from MOOCs’ instructional design aspect. Although the number of the participants who responded to the survey questionnaire is small, the positivity about MOOCs in ESL domain turns out to be wholesome. Thus the paper aims to explore opinions about strengths and weaknesses of MOOCs on ESL/ELT and evaluate how beneficial they have been for those who attended it. The study blends three aspects, awareness about MOOCs leading to enrolment in them (this helps determine the motivation required for continuing professional development as that is self-effort), narrowing it down to English teachers in Pakistan and their perusal of new technological developments in pedagogy and having a look at the impact of MOOCs on the continuing professional development of teachers teaching English as a second language.

The study looked for responses to the following research questions:

RQ1. What is the level of general awareness of Pakistani English teachers about MOOCs?

RQ2. Do MOOCs help Pakistani English teachers improve their skills for teaching English as a second language?

RQ3. Do MOOCs help Pakistani English teachers improve their instructional design?

Literature Review

Teachers’ professional development is a major concern for educational institutions all over the world. However, getting professional development opportunities on a continuous basis to keep one self up-to-date and motivated is really challenging. MOOCs provide one such opportunity for continuing professional development for teachers on a mass level (Misra, 2018). MOOCs have the potential to not only help for standardized and site based learning but also for self-directed professional development of teachers (Gaible &Burns, 2005). Thus MOOCs can dramatically redirect teachers’ professional development in future through capacity building and skill development (Richards, 2014). Dikke and Faltin in their 2015 study found 130 MOOCs available online about teachers’ professional development. They were mostly is English and Spanish languages encompassing teaching skills including language teaching, science teaching, use of ICT in classrooms and soft skills (Dikke & Faltin, 2015). The growing increase of MOOCs for professional development determines their effectiveness for CPD as they provide a solution to cost and time related problems teachers face for professional development otherwise (Marquis, 2013). MOOCs can help teacher improve their teaching by observing other teachers teach, joining discussion boards, going through a student feel online, learn anew in a structured manner and avail appropriate resources free of cost (Bali, 2013). Therefore a combination of MOOCs and professional development is a win-win situation altogether (Jobe, Ostlund & Svensson, 2014).

Language MOOCs are a recent development with great potential in an international educational scene where EFL/ESL learners generally do not have exposure to native teachers and may not get admission to foreign universities due to high costs based on currency value differences. MOOCs provide an opportunity of direct language exposure as well as communicative learning because students from multiple backgrounds and multiple first languages interact for learning a new language or improve the previous knowledge of the target language. Thus MOOCs facilitate a multicultural experience that supports learners in enhancing their sociolinguist, psycholinguistic and discourse aspects of the target language. Still, it can be contested and challenged whether MOOCs really help in professional development of second/foreign language teachers because of the instructional design, motivation factors, and quality and dropout rates (Bárcena, Read, Martín-Monje, & Castrillo, 2014).

MOOCs have not been extensively studied with particular reference to second language improvement and need much more research as they can be a potential source of students’ language improvement (Anzai, Ostashewski, , Matoane, & Mashile, 2013). One of the reasons may be the lack of MOOCs on ELT as there is a small number of language learning MOOCs which may be growing in number gradually on various MOOCs offering platforms (Godwin-Jones, 2014). The number is far less in professional development of language teachers. It is not necessary that MOOCs on English language can do the magic as most of the MOOCs even in sciences and humanities are in English language and can help improve English language skills of non-natives by expanding their vocabulary and communication skills (Rybushkina & Chuchalin, 2015). The largest number of MOOCs available currently are in English language (Edlin, 2018). Therefore,, Freihat and al Zamil (2014) consider MOOCs quite effective for improving listening comprehension of EFL students. Wu, Fitzgerald and Witten (2014) consider MOOCs a very useful way of learning domain specific language.

MOOCs are a cost and resource effective means for the professional development of EFL/ESL teachers. They can be very convenient for those who want to improve their language skills (Godwin-Jones, 2014). They can be very useful for lifelong learning; however, the organizations need to consider MOOCs as a valid source of professional development like other degrees so that teachers get more motivated for attending MOOCs (Jobe, Östlund & Svensson, 2014). MOOCs need to be improved on in certain ways for professional development, for example, more opportunities for networking of teachers, accreditation, and the facility of reusing resources for teachers (Seaton et al., 2014). In this regard, professional development variations in face-to face, online and technology-mediated contexts needs to be given consideration as well (Brooks & Gibson, 2012). MOOCs can be beneficial for English literature teachers’ professional development too. For example, Manning, Morrison and McIlroy (2014) attended Coursera MOOC ‘Fantasy and Science Fiction: The Human Mind, our Modern World’ and found it really interesting and useful as the goals of the course were aligned with the researchers’ goals of English literature capacity building. They find MOOCs really useful for teachers as they do not clash with their busy schedule and can be attended after university/college schedule (Manning, Morrison & McIlory, 2014)

Method

The target population of this study was all English language and literature teachers in Pakistan. For this purpose, an online survey questionnaire was administered via various Facebook groups, via email, and also in person. The question items were very carefully designed by the researcher to analyse teachers’ personal improvement of English language and literature knowledge as well as professional development. Apart from getting the demographic details of the participants, the questionnaire is divided into three parts. The first part investigated teachers’ general awareness about MOOCs. The second part inquired about their impact on teachers’ four skills for learning and teaching English as a second language. The third part focused on professional development key aspects like lesson planning, selection of material, assessment methods and test item writing etc. Lastly the questions focused on overall usefulness of MOOCs and their adaptation in Pakistani universities either as they are or by developing new MOOCs. The study was not intended to be a small scale study initially as the researcher intended to get at least 100 respondents’ opinion, but as many Pakistani English teachers are not familiar with the concept of MOOCs, and did not respond positively, finally convenient sampling was used to gather data. The data for this study was gathered from 2016-17. One hundred teachers were asked whether they have successfully gone through at least one MOOC and only 32 responded positively and filled out the questionnaire.

The results have been presented question by question where it was important to display the options given to the respondents. For the 5-point Likert scale items from strongly disagree to strongly agree descriptive statistics have been used to validate data and interpret results. Co-relation has been applied to further validate the results to see the relationship of MOOCs effectiveness on the overall improvement of the various aspects mentioned in the questionnaire.

Results

The first part of the survey collected demographic details of the participants which are given below (Table1).

Table 1. Demographic Details of the Participants

The demographic details show that the majority was that of females, belonging to the province of Punjab, with the qualification of M.Phil which is the second highest degree after Ph.D in Pakistan. Most of them fell between the age group 21-30 and were lecturers i.e., in the early years of their career.

The second part of the survey collected participants’ opinions about MOOCs experience with particular reference to improvement in English as a Second Language (ESL) and their professional development in this regard. The reliability of the questionnaire was 0.830 (Table 2).

Table 2. Reliability Statistics

The first question investigated the number of MOOCs attended. The graph below displays the results (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of MOOCs Attended

The results display that most of the participants attended fewer than 10 MOOCs.

Question 2 probed how the participants got to know about MOOCs. The graph below displays the results (Figure 2).

Figure 2: How Respondents Were Introduced to MOOCs

The results show that most of the participants got to know about the MOOCs either from a friend or through Facebook posts.

Question 3 investigated the participants’ knowledge about the difference between c and x MOOCs. The graph below displays the results (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Familiarity with the Difference Between C and X MOOCs

The results show that most respondents were not aware of the difference.

Question 4 asked respondents to state the difference between C and X MOOCs. The graph below displays the results (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Exact Difference Between C and X MOOCs

Only one respondent knew the difference as shown in the graph.

Question 5 asked about respondents’ areas of interest for attending MOOCs. The graph below displays the results (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Areas of MOOCs

The results show mixed opinions with most of the participants of linguistics area (34 %) closely followed by ELT (33%). Nineteen percent (19%) chose writing and 12 % literature MOOCs to be attended.

Question 6 probed about skill improvement by MOOCs. The graph below displays the results (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Reported Improvement of Skills

The results show improvement in all areas with writing at top with 24% of teachers mentioning that skill.

Question 7 asked about the improvement of teaching skills in particular. The graph below displays the results (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Reported Teaching Skills Improvement

The results show improvement in all areas with minor differences. Twenty nine (29 %) mentioned lesson planning, 25 percent test item writing, 23 % curriculum development and 22% class management.

Question 8 asked about the most useful aspect of MOOCs. The graph below displays the results (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Most Useful Aspects of MOOCs as Reported by Respondents

The results show that the participants found all areas useful but videos were found to be particularly useful as 20% of participants mentioned them. Sixteen percent (16%) mentioned audio lectures, 15% assignments, 15% quizzes, 1 % PPTs, 11% handouts, and 10% the teacher as the most helpful component.

Question 9 asked about the best MOOCs platform. The graph below displays the results (Figure 9).

Figure 9. The Reported Best MOOCs Platform

Coursera was the most familiar site with 44% choices. Nineteen percent (19%) chose Futurelearn, 15% Edx, 15% Linguistic Campus, and 7% Alison courses.

The next round of questions was purely quantitative and a 5-point Likert scale was used. The descriptive statistics have been given below (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics of Questionnaire Items

The descriptive statistics show that MOOCs helped teachers in improving their language as well as teaching skills.

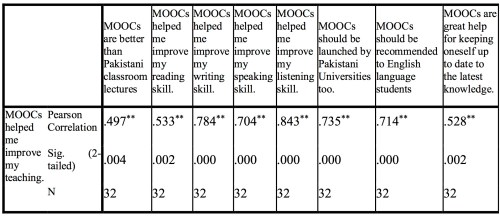

To further validate the results co relation was determined through the use of SPSS. Below is the description.

Table 4. Pearson Correlation

H0: Moocs do not help improve teaching English as a second language

H1: Moocs help improve teaching English as a second language

As the Sig values are less than level of significance 0.05 so we can say that the null hypothesis is rejected and alternative hypothesis is accepted.

Discussion

The professional status of the respondents reveals that most of them were highly qualified disseminating education at a higher level. The age group of the majority reflects the early career aspiring time period wherein one is in dire need of professional capacity building as well as has the motivation and energy for that too. Therefore MOOCs as a disruptive educational training platform can be extremely helpful as well as attractive for them. The majority of the respondents had attended less than 10 MOOCs, only three had attended more than 10 and one more than 20. Majority of them were introduced by a friend/colleague/ teacher and only two came across while surfing net and one got to know via the social medium of Facebook. This reflects that MOOCs were found quite helpful therefore recommended to others. Except one of the participants, none of them was aware of the different types of MOOCs, which shows that MOOCs as innovative disruptive educational practice were not the interest but learning through them got positive response. The participants don’t seem to be much interested in what MOOCs are, how they started, what was the rationale behind them etc. They got introduced to them as free courses and found them good. Therefore, it can be concluded that they are the popular discourse so far disseminated through in person communication and it’s only after attending them completely that teachers can formulate some opinion about them. The meta-learning about MOOCs was quite unsatisfactory. One of the reasons for this could be that MOOCs are more researched by e-learning domains.

As far as the domains of linguistics, English language teaching and English literature are concerned, most of the participants found linguistics and ELT MOOCs helpful. There can be three reasons for less participation by literature teachers, one the interest level of the participants for updating knowledge, second the lack of availability of good MOOCs in English literature and third less technology use by literature teachers in the classrooms. Moreover, the frequency of general English language improvement MOOCs is a major reason to interest teacher from the domains of linguistics and ELT. The digital humanities are still to be popularized in Pakistan and most of the literature teachers are not technology savvy or at least not following MOOCs.

As far as the response to skill improvement is concerned, the respondents felt that writing skill was all the more improved followed by speaking, reading and listening and teaching respectively. It is pertinent to mention here that English is a second language even for teachers in Pakistan. The most popular variety of English being used in the classrooms is Pakistani English. In many instances even bilingualism is also very common as teachers code mix and code switch from English to Urdu and vice versa. As teachers are a product of the same system, their professional development does not mean the improvement of teaching skill set, it also refers to further improvement in four strands of English language. The MOOCs gave exposure to their ears for native spoken English as well to authentic reading material and cross check of written English by multiple nationals. The results explicitly convey that the four basic language skills of the second language teachers required serious improvement which automatically led to the general improvement of teaching skills.

The opinions about teaching skill set improvement reflect that MOOCs improved their lesson planning and assessment question writing skills followed by class management skills and curriculum development. As most of the university teachers in Pakistan begin teaching without a professional training, MOOCs turn out to be free teacher training sources. The presentation of lesson plans and test items developed metacognition in teachers about how to devise instructional design for their classroom. The respondents found all aspects of MOOCs helpful with videos and quizzes on top followed by audio, assignments, PPTs and handouts. The teachers learnt about planning lessons, designing assessment, selecting and managing resources. Coursera was the most used platform by this small sample size followed by Linguistic Campus, Future Learn and Edx. This also reflects the presence of reasonable number of subject specific courses on at least some platforms. Course presentation could be another reason for liking Coursera all the more.

Overall, there was a strong agreement that MOOCs’ instructional design was far better than Pakistani classroom teaching in the domains of ELT/Linguistics/Literature as they were interactive. Although assessment was mostly quiz based, the immediate feedback was appreciated. The teachers could also download videos and lecture notes for future use. Above all the respondents found much higher concept clarity than in Pakistani classrooms as they found MOOCs more organized because of carefully and appropriately selected presentation and reading materials. They also got an exposure to native teacher/teaching which was found helpful. Most of them strongly agreed about the improvement of language and teaching skills as they kept them updated about latest development in their domain knowledge. They also recommended the introduction of MOOCs to all students, its integration in the classrooms as well as attempts by Pakistani universities to launch Pakistani MOOCs as well.

The most interesting aspect of the research was that the respondents highlighted some weaknesses of the MOOCs. Assessment methods based on quizzes and peer assessment were criticized. The due dates or hard deadlines were not liked. The variation in time zone created problems along with the bandwidth issue of their internet connections. They also found no direct interaction with teacher as a major weakness of MOOCs. These points reflect the need to improve the instructional design of MOOCs from teachers’ professional development perspective.

The best part was the respondents’ inspiration to introduce their students to MOOCs and use the MOOCs in the classroom. This may eventually lead to blended or flipped classroom of which teachers are not still aware. The respondents were imaginative enough to respond positively to the question that Pakistani universities should also jump into developing MOOCs.

Conclusion

The study is significant enough as it traces the level of awareness about MOOCs and thereby the frequency of attending them by English language/literature university teachers of Pakistan. Although it is a small scale study limited to one domain, the results can be generalized to many other subjects as the general awareness level of MOOCs is more or less the same and from a professional development point of view more motivation to attend MOOCs is required. For English language/literature university teachers of Pakistan, it is important to have a native exposure for improving integrated skills as well as teaching skills. This would help them impart better knowledge in their classroom through a better set of instructional design. They can also introduce their students to MOOCs as well as make them a part of their face to face classrooms for blended learning. Students can use MOOCs when they are inside or away from their campus as in flipped classrooms, and discuss the learning from MOOCs with their peers and teachers in the classroom (Manning et al., 2014). Teachers can also incorporate a MOOC or use material from various MOOCs in their classes (Bruff, Fisher, McEwen, & Smith, 2013). MOOCs can turn out to be free teacher training programs of high quality as the current options for ELT trainings are either by Higher Education Commission (HEC) or British Council and Directorate of Staff Development (DSD) which are either paid or based on nominations’ tedious procedure. Teachers’ must have intrinsic motivation to make use of MOOCs whether they are popularized by any such funding agencies or not.

The study calls for future research, for example, seeking students and teachers’ perceptions about MOOCS in other disciplines, the suitability and need of developing Pakistani MOOCs with national flavour, the cultural sensitivity of available MOOCs for all countries and in particular Pakistan. Experimental studies about the effectiveness of blended learning or a flipped classroom by using MOOCs inside or outside the classroom should also take place to measure the improvement in English language right away. The design aspect of professional development MOOCs is not a much researched area (Vivian, Falkner & Falkner, 2014), so more research needs to be conducted in this area too.

Limitations of the Study

The study includes few participants and although the data collection was aimed to be simple random sampling, when people were asked about their awareness about MOOCs, the response rate was very low. Initially the sample size was to be selected from the universities but due to the low response all English teachers i.e., universities and colleges were selected for convenience sampling. Moreover, literature courses were also made a part of the study. With an increase in the number of TEFL/ TESOL MOOCs paid specializations by Coursera and increase in English language courses by Futurelearn in 2016, another study with large data set should be conducted. However, the researcher believes that results for English language teachers can be generalized as MOOCs have been viewed very positively. Also with the introduction of a paid feature, motivation for attending MOOCs would remain low. However, more awareness about MOOCs and measures to enhance motivation for constant capacity building through MOOCs is required.

Notes on the contributor

Ayesha Perveen is an Assistant Professor of English Language and Literature and Head of the Department of English at Virtual University of Pakistan. She has more than 15 years of experience of teaching English language and literature in face-to-face and online modes. Her educational interests include adapting established educational theories for open and distance learning or creating new ones in view of the existing challenges. She is an interdisciplinary researcher and her research interests include open and distance learning, blended learning, learning analytics, critical theory, critical discourse analysis, critical pedagogy, English language teaching and literatures written in English. She is also the co-editor of Virtual University hosted Journal of Distance Education and Research (JDER).

References

Anzai, Y., Ostashewski, N., Matoane, M., & Mashile, E. O. (2013). What about MOOCs for language learning?. In Proceedings of World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education (pp. 557-561). Las Vegas, NV, USA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Retrieved March 25, 2018 from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/114923/.

Bali, M. (2013, July 12). 5 reasons teachers should dip into MOOCs for professional development. MOOC news & reviews. Retrieved from http://moocnewsandreviews.com/5-reasons-teachers-should-dip-into-moocs-for-professional-development-2/

Barab, S. A., Makinster, J. G., Moore, J. A., & Cunningham, D. J. (2001). Designing and building an on-line community: The struggle to support sociability in the inquiry learning forum. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(4), 71-96. doi10.1007/BF02504948.

Bárcena, E., Read, T., Martín-Monje, E., & Castrillo, M. D. (2014). Analysing student participation in Foreign Language MOOCs: A case study. EMOOCs 2014: European MOOCs Stakeholders Summit, 11-17.

Borko, H. (2004). Professional development and teacher learning: Mapping the terrain. Educational Researcher, 33(8), 3-15. doi:10.3102/0013189×033008003

Brooks, C., & Gibson, S. (2012). Professional learning in a digital age. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 38(2), 1-17. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ981798.pdf

Bruff, D. O., Fisher, D. H., McEwen, K. E., & Smith, B. E. (2013). Wrapping a MOOC: Student perceptions of an experiment in blended learning. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(2). Retrieved from http://jolt.merlot.org/vol9no2/bruff_0613.htm

Dikke, D., & Faltin, N. (2015). Go-Lab MOOC – An online course for teacher professional development in the field of Inquiry-based science education. 7th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Jul 2015, Barcelona, Spain. Retrieved from https://telearn.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01206503/file/EDULEARN_MOOC_final.pdf

Edlin, C. (2018). MOOC Course Prospectus: Adding Value as a Physical Institution in an Age of Ubiquitous Digital Access and Massive Open Online Courses. Relay Journal. Retrieved from https://kuis.kandagaigo.ac.jp/relayjournal/issues

Freihat, N., & Al Zamil, A. J. (2014). The effect of integrating MOOCs on Saudi female students’ listening achievement. European Scientific Journal, 10(34), . Retrieved from http://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/viewFile/4828/4537

Fyle. C. O. (2013). Teacher education MOOCs for developing world context: Issues and design considerations. In the proceedings of linc. Mit.edu June 16-21, 302-313. Retrieved from http://linc.mit.edu/linc2013/proceedings/Session3/Session3Fyle.pdf

Gaible, E., & Burns, M. (2005). Using technology to train teachers: Appropriate uses of ICT for teacher professional development in developing countries. Washington, DC: infoDev / World Bank..Retrieved from http://www.infodev.org/en/Publication.13.html

Godwin-Jones, R. (2014). Emerging technologies global reach and local practice: The promise of MOOCs. Language Learning & Technology, 18(3), 5–15. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/issues/october2014/emerging.pdf

Gore, J., & Ladwig, J. (Nov. 2006). Professional development for pedagogical impact. Paper presented at the Australian Association for Research in Education Annual Conference, Adelaide, AU. Retrieved from http://www.aare.edu.au/06pap/gor06389.pdf

Hicks, C. (2015, March 3). Why MOOCs are great for teacher development. Retrieved from http://www.edudemic.com/5-moocs-educators-should-take-as-students/

Jobe, W., Östlund, C., & Svensson, L. (2014). In M. Searson & M. Ochoa (Eds.), Proceedings of SITE 2014–Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 1580–1586). Jacksonville, Florida, United States: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Retrieved from https://oerknowledgecloud.org/sites/oerknowledgecloud.org/files/proceeding_130997%20(3).pdf

Killion, J., & Williams, C. (2009). Online professional development 2009. MultiMedia & Internet@Schools, 16(4), 8-10.

Marquis, J. (2013, May 21). Why MOOCs are good for teacher professional development. Retrieved from http://www.onlineuniversities.com/blog/2013/05/why-moocs-are-good-for-teacher-professional-development

Pappano, L. (2012). The year of the MOOC. The New York Times, November 4, ED26. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-aremultiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html?_r=0

Perveen, A. (2015). Critical Discourse Analysis of Moderated Discussion Board of Virtual University of Pakistan. Open Praxis, 7(3), 243-262. Retrieved from http://openpraxis.org/index.php/OpenPraxis/article/view/152Manning, C., Morrison, B. R., & McIlroy, T. (2014). MOOCs in language education and professional teacher development: Possibilities and potential. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(3), 294-308. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep14/manning_morrison_mcilroy/

Misra, P. K. (2018). MOOCs for Teacher Professional Development: Reflections and Suggested Actions. Open Praxis, 10(1), 67-77. Retrieved from https://openpraxis.org/index.php/OpenPraxis/article/view/780/425

Richard, A. (2014). How do MOOCs fit into professional training? Retrieved from http://www.colloquium-group.com/how-do-moocs-fit-into-professional-training/?lang=en

Rybushkina, S. V., & Chuchalin, A. I. (2015). Integrated approach to teaching ESP based on MOOCs. In Proceedings of the 43rd SEFI Annual Conference 2015 – Diversity in Engineering Education: An Opportunity to Face the New Trends of Engineering, SEFI 2015 European Society for Engineering Education (SEFI).

Seaton, D. T., Coleman, C. A., Daries, J. P., & Chuang, I. (2015). Teacher enrollment in MITx MOOCs: Are we educating educators? Educause Review, 2. Retrieved from http://er.educause.edu/articles/2015/2/enrollment-in-mitx-moocs-are-we-educating-educators

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic books.

Vivian, R., Falkner, K., & Falkner, N. (2014). Addressing the challenges of a new digital technologies curriculum: MOOCs as a scalable solution for teacher professional development. Research in Learning Technology, 22. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v22.24691

Wu, S., Fitzgerald, A., & Witten, I. H. (2014). Second language learning in the context of MOOCs. In S. Zvacek, M. T. Restivo, J. Uhomoibhi, & M. Helfert (Eds.), Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education, Volume 1 (pp. 354–359). Barcelona, Spain: SCITEPRESS. http://doi.org/10.5220/0004924703540359