Jessie Choi, Hong Kong Education University

Choi, J. (2017). The metamorphosis of a self-access centre in Hong Kong: From theory to practice (a case study). Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(1), 23-33. https://doi.org/10.37237/080103

[Download paginated PDF version]

Abstract

The purpose of this case study is to illustrate the changes that took place in a self-access centre of a Hong Kong university. The author describes how she adopted several new approaches for the Centre after taking over the post of the Centre Manager. In the face of the changing needs of users and the University and the growth of e-resources, the author tried to convert the Centre into a social gathering place where different kinds of interactions could be promoted. Research was conducted into the theories that had been adopted to make the Centre an attractive place for the students of the university. The re-shaping story of this Centre might offer some ideas or thoughts for educators or language centre managers in their own situations.

Keywords: Self-access centre, integrated or push-pull approach, people-focused approach, layout design

The university to which the Self-access Centre of the current case study belongs is a government-funded institution that offers teacher education in Hong Kong. It provides doctorate, master and undergraduate degrees; postgraduate diploma, certificates; and in-service training programmes. Besides academic and research programmes on teacher education, it also offers complementary courses in the disciplines of social sciences and humanities. Students can receive specialist study and a broad-based training in becoming qualified teachers and professionals in Hong Kong.

The Self-access Centre is under the governance of the Language Centre and is tasked with the responsibility for the planning, design, delivery, support and management of the informal language learning activities in the University. The Centre provides activities to support the learning of Chinese, Cantonese, Putonghua and English.

Up until 2015, the number and variety of workshops was rather limited since the Centre did not have its own teaching staff. It had to rely on the staff of Language Centre to conduct ad-hoc, one-off or irregular workshops or consultations. With the availability of more and more online learning resources and the limited number of activities offered at the Centre, students seemed less interested in visiting the Centre.

Beginning in 2015, the newly appointed Centre Manager (the author) started to look for new ways to tackle the above problems and to achieve the mission of the Self-access Centre, which is “to support both independent learning and proficiency development in English, Putonghua and Chinese”. She was inspired to begin researching self-access centres and self-learning. By reflecting on her own experiences and taking students’ feedback into account, the manager realized that physical learning material was no longer a strong attraction. The creation of a community of students through various kinds of social and academic events/activities in the Centre was crucial. One of the best approaches to attract students was to work closely with the curriculum of the Language Centre. By offering more interesting and fun activities, it was hoped that students could be more willing to come to the Centre to mix with tutors and peers, thus developing a social bond that could motivate them to come more often.

Since September 2015, various kinds of activities for learning Putonghua, English and Chinese have been offered by the international tutors and teaching staff of the Language Centre. The activities include consultations, cultural and academic workshops, English cafe, buddy scheme and large-scale festive events, such as Halloween night. By their involvement in self-access activities, students are expected to construct knowledge by interacting with the people around them. The Centre facilitates learning by providing activities that encourage independent language learning and development of various language skills. The self-access activities provided opportunity for students to engage in different forms of activities to enrich their learning, not only to promote language learning, but more importantly, to support independent learning.

The case study reported on here is an attempt to understand the theories the author adopted in order to transform the self-access centre.

Design Theories

“Integrated” or “push-pull” approach

The first major problem observed was that students had not been interested in doing self-learning activities in the Centre in the past few years. Gardner and Miller (1999) suggested using project-based learning as a means to engage students more in their self-learning by pushing them to work with their peers outside their regular classroom lessons in some project work in which “classroom-based learning can be linked with a self-access centre” (p. 167). It was difficult for students, especially first-year ones, to know how they could use the self-access centre to help with their learning, it was thus important that teachers could help to “push” their students to visit the Centre by giving them tasks that had to be finished there. The Centre could then provide interesting and interactive tasks that “pulled” students to continue their visits. These integrated or push-pull activities could be used to encourage interaction with people in the Centre. This approach might help learners make their first try in the activities of the Centre and became more accustomed to being a “self-learner” beginning by being a “classroom learner”. The approach adopted in this case study followed the “push-pull” approach presented by Croker & Ashurova (2012). The author suggested that a “push-pull strategy served as a bridge between the language classroom and a self-access centre, helping learners make the first steps in their transition from being a “classroom English learner” to becoming a “SALC English user”. One of the possible ways was to integrate activities of the self-access centre with the existing English curriculum in order to encourage the participation of students (Gardner & Miller, 2014). As such, students would be able to make effective use of the Centre and develop their autonomy and independent learning skills (Gardner & Miller, 2014).

People-focused approach

Another problem was that students did not seem very interested in visiting the Centre. According to Croker and Ashurova (2012), it was crucial to attract students by establishing a strong social bond between learners so as to make language learning interesting in a relaxing and enjoyable environment where they could use the target languages with the people there. By providing more and different ways, formal or informal, for students to work with and learn from one another, the self-access centre could become a gathering place for social learning. As Allhouse (2014) pointed out, a self-access centre could still be a popular place for students to socialize with one another even though the Internet might have dampened the desire of some students in visiting the centre. If they would like to have some real interactions with people for practising languages, they still needed to find them in the self-access centre. This meant that the Centre had to provide frequent opportunities for students to socialize and practise in person with tutors or other students in either a formal or informal way. This was important as it could create a social bond among students so that coming to the Centre could be a long-term need or motivation for them. For instance, in the English cafe that promoted informal English speaking, students could come alone or with peers to meet the tutors there to talk about the things they were interested in. Each day or week the group could meet, chat casually and have discussions in English. Again, the author tried to promote the self-access centre as being available as a platform for social gathering or/and language learning.

Effective environment layout and design

To deal with the problem of less patronage faced by the self-access centre, attention was also put on creating a welcoming learning environment. As pointed out by Benson (2001), self-access centres are sometimes established “without any strong pedagogical rationale” (p. 9), which indicates that strong pedagogical principles were not adhered to in most of the centres at present. In addition to the easy access of self-learning material that could help students to make the effective use of the Centre (Gardner & Miller, 1999), due care should be paid to the use of space and the establishing of a welcoming and motivating learning environment (Barrs, 2010). According to Riley (1995), “… everything should be done to make a resource centre of any kind welcoming, light, airy, colourful….”. Edlin (2016) suggested the following six design principles to help with language learning in a self-access environment:

Table 1. Self-Access Design Principles (Edlin, 2016)

Initiatives/Actions Taken

Based on the above theories, the following initiatives were taken in order to make the Self-access Centre of this study a new social learning place:

Table 2. A Summary of the Actions Taken

Since research showed that the self-access learning experience of students was linked with their needs from formal curriculum, year one and two students were given the choice of joining the English workshops and the language advising sessions of the centre in order to fulfil part of their English enhancement course requirements, in which students had to complete some out-of-class English activities. Students could complete their tasks by choosing to enrol into the activities of the centre themselves, but at the same time students could be made very aware of the resources and activities available there in the hope that they would use these resources and activities later by themselves. Furthermore, students could know more about the help offered by the international tutors of the centre as they would get acquainted with them after joining their first activities in the centre. The awareness of resources and activities was raised and developed through the curriculum-integrated tasks, so that when students encountered any English learning problems, they would remember that the centre could provide help for them.

Incorporating self-access activities into curriculum

Offering formal and informal language learning

Interesting activities. A wide range of interesting activities was provided for students to acquire languages in a fun, interesting, formal and informal environment. The author understood that the Centre should not be solely a place for housing material or coming for language advice. And, ultimately, the author made it a place for having enjoyable, valuable, and unforgettable learning experiences. The Centre was expected to be a hub for students to gather and work collectively towards a higher level of language competence. The service needed to be more than just good—it needed to be consistently good. Specifically, the activities were expected to meet the needs of users and the tutors were expected to be available and helpful in assisting users in the language learning process. Hence, academic, fun and cultural workshops and language consultation sessions are now offered at the Centre.

English cafe. The English cafe was aimed at providing more informal, social and relaxing environments for students to enhance their language learning competencies. This could allow tutors to develop a closer relationship with users that student learning could be accelerated if students and teachers could feel more connected with one another. It was hoped that the Centre would be a place containing a team of professionals that students could rely on. The author created a student base that was not only growing, but completely loyal. The English café is the newest attempt which the author introduced into the Centre in order to provide a more informal means of enhancing the contact with English among students and the tutors. The English café is open daily for students to engage in social chats and activities with tutors. It is expected that more and more students could come to talk to the international tutors.

English language buddy scheme. The English language buddy scheme was designed for all undergraduates of the University. Students who take part in the buddy scheme are paired up with an international tutor. The aim of the scheme is twofold. On the one hand, it helps international tutors to integrate into the community of the university and to enhance their understanding of Hong Kong culture. On the other hand, it helps students to befriend an ambassador from abroad, and learn about various foreign cultures while developing their English language skills. Under the buddy scheme, students are paired up with current international tutors who provide language help and friendship to students. Students meet their buddy tutors and peers once or twice a week on campus, at a time and venue agreeable for both parties. The groups meet regularly and do fun activities together such as having meals, watching movies, or playing sports. Each international tutor is affiliated with one faculty helps supervise two groups of students from the affiliat faculty. They work together with their student buddies to schedule their activities every month. There are about 100 student buddies from various programmes enrolled in the buddy scheme.

Improving the usability, ease of use, and visual appeal of various online platforms

Online booking system. The goal of effectively designing the online platforms was to make the experience and services of the Centre transparent to students and staff. Rather than hiding resources, the author believes the Centre should bring them to all users, creating a one-stop, easy-to-navigate experience. In addition, students should be able to easily book activities through the system. In this aspect, the author re-designed the online booking system with an outside design company. All the activities of the Centre could be booked by students via the online booking system at anywhere and anytime.

New website. Additionally, the author, with the help of a student helper, worked to revamp the website of the self-access centre to make it more informative, attractive and inviting. The hope of the author was that whether students access our online booking system and website, the Centre should be the place to enable them to advance their learning experiences. The newly-designed website comes with more features which includes details of forthcoming activities, such as workshops and consultations to be held by international tutors, Putonghua and Chinese teams at the centre, online registration for the activities, resources for language learning, and much more. Also, online evaluations of workshops and consultations could be done through the website. The new website was designed with the end user in mind. It was hoped that the website design and new features could help users easily access the information they needed.

Redesigning Centre space and re-organising resources

Physical redesign. The principal challenge for the author as the Centre manager was to redesign the Centre as a learning environment that was transparent and sufficiently flexible to support the various kinds of learning activities. To accomplish this, the author evaluated the effective use of space by talking to staff and students and assessed new placements of services and configurations of learning spaces in response to changes in user demand. Only then could a unique physical response to the needs and aspirations of students be achieved. The author hoped the above actions could enhance the excitement and adventure of students in the Centre. The author redesigned the physical space of the Centre. High bookshelves were taken down to make space for more discussion and work areas. New furniture was installed to attract users. Books and multi-media sources were checked for both usefulness and currency and re-organised in a more useful manner. Clearer signage was made to provide better directional guidance. Rooms were re-structured to provide space for workshops and consultations. Notice boards were re-designed to allow effective dispatch of information.

Reorganization of resources. The author re-organised the Centre resources of all languages and put them in a newly developed database. She also changed the coding for resources and labelled the material to allow better access to the information. In addition, existing and new online resources were organised and placed on the new Centre webpage for easy access. A new resources database was then developed with the new coding system with the printed resources properly labelled. Unused or outdated resources were discarded to allow more space for updated and more useful items.

Providing a supportive environment and professional experience

The Centre offered various activities to develop internationalization in order to stimulate mutual learning and an exchange of experiences. The Centre now uses Facebook and Instagram to connect the students and international tutors. In addition, the publication of the “Newsletter” helps to promote internationalization. Also, assistance offered voluntarily by tutors on skills, such as CV writing and interview practice, has been welcomed by students.

Evaluation

Entry record

In 2015-16 academic year, 13284 students visited the Centre (see Table 3). Majority of the visitors were full-time Year 1 and Year 4 students. This might be due to the language activities they were required to complete by their course teachers and the language tests they had to take to fulfil the language exit requirements. There was a dramatic growth in the number of students visiting the Centre from previous years (see Table 3).

Table 3. Number of Students Visiting the Centre

| Year | Visitor Numbers |

| 2015-16 | 13284 |

| 2014-15 | 4727 |

| 2013-14 | 4850 |

Attendance Data

The number of of participants in the activities in the 2015-16 academic year increased to over 2498 and 4669 in the first and second semester respectively (see Table 4). Tnumber of participants was significantly higher than in previous years

Table 4. Activity Attendance Data

| Year | Attendees |

| 2015-16 | 7167 |

| 2014-15 | 677 |

| 2013-14 | 2016 |

Activity Data

The Centre developed a range of learner support initiatives designed to draw more students into the learning centre resulting in more than 13284 students visiting the Centre in 2015-16. A total of 555 academic, cultural and fun workshops on specific language learning needs, 1424 one-to-one consultations (including the sessions for helping students’ learning tasks for courses), and 723 language support activities for the English programme were introduced according to student demand. In addition, there were also the opportunites offered by the English Cafe and the buddy scheme. Also, as an attempt to help students to learn from one another, the Centre provided student-led Putonghua consultation sessions. These are proving to be very popular and valuable to our students.

Activity effectiveness

Student’ satisfaction levels with workshops and consultations are assessed immediately after the activity via an online bi-lingual survey designed to capture feedback on the activity, tutor, development of English proficiency and independent learning capability and “customer service”. Students also have the option to leave open comments, anonymously if they wish. Some details on the responses are shared below.

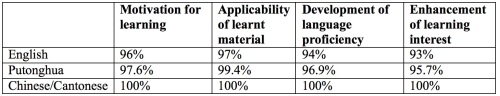

Workshops and consultations. The results of a survey presented in Table 5 were based on a total of 2121 completed surveys. The survey represented the perceptions of the workshop participants of the English, Putonghua, and Chinese/Cantonese workshops. The value of the workshop to the participants received very favorable scores on a scale from Strongly disagree to Strongly agree. The value was calculated as the sum of the responses for “Agree” and “Strongly agree” on the survey items in the following areas: motivation for learning. applicability of learnt material, development of language proficiency, enhancement of learning interest.

Table 5. Value of Workshops

The majority of the survey takers felt that the language workshops conducted by the Centre were very useful to them as the ratings for the identified items for the value of workshops were very high (> 90%). Many also commended the useful feedback from tutors in the workshops. The overwhelming majority of the participants highly rated the general effectiveness of the workshops. Comments received from participants were generally favorable and constructive.

As for consultations, the participants were asked to rate the usefulness of the advice they received. A total of 683 responses were received. Overall, the majority of respondents found the sessions useful in terms of resources that were recommended and the feedback that was given. Also, they felt that the sessions helped them to know more about the language they sought help in. Table 6 illustrates detailed responses of participants for their evaluations on consultations.

Table 6. Value of Consultations

English cafe. There was no formal procedure for the collection of students’ comments in the English cafe as it was designed to be an informal place for linguistic and cultural exchange. No prior booking was required and students could come at our opening time to chat or play games with the tutors on duty. Students were only invited to sign the “Guest book” at the end of the visit, which was totally voluntary.

Conclusion

This paper summarised the changes introduced to the self-access centre during the past two years. Links with the formal curriculum and the other approaches could attract students to participate in informal social learning activities. The results suggest that the approaches adopted were effective and the author would like to continue introducing new activities and activity formats using similar approaches to support independent learning in the coming years. Further in-depth research may be required to look into new approaches and changes that can be brought to the Centre.

Notes on the contributor

Jessie Choi holds a doctoral degree in Education (Applied Linguistics and TESOL). She has been involved in English teaching in the tertiary level for more than ten years. She has taught undergraduate programmes for second language learners in General English, Academic English and Business English. The author has research interests in peer writing, online learning and the use of the computer in language education. She has conducted studies in online writing collaboration, peer discourse and the use of e-portfolios.

References

Allhouse, M. (2014). Room 101: The social SAC. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(3), 265-276. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep14/allhouse/

Barrs, K. (2010). What factors encourage high levels of student participation in a self-access centre? Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(1), 10-16. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun10/barrs/

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

Croker, R., & Ashurova, U. (2012). Scaffolding students’ initial self-access language centre experiences. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(3), 237-253. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep12/croker_ashurova/

Edlin, C. (2016). Informed eclecticism in the design of self-access language learning environments. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(2), 115-135. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun16/edlin/

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (2014). Managing self-access language learning. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press.

Riley, P (1995). Notes on the design of self-access systems. Mélanges n° 22 (1995 – Spécial Centre de Ressources). Retrieved from http://www.atilf.fr/spip.php?rubrique557