Diego Navarro, Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand

Navarro, D. (2014). Framing the picture: A preliminary investigation into experts’ beliefs about the roles and purposes of self-access centres. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(1), (8-28). https://doi.org/10.37237/050102

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

This paper presents results from phase one of a large-scale, two-phase research project investigating self-access centre (SAC) experts’ (Centre Directors; Centre Managers; Centre Coordinators; Learning Advisors) beliefs about the roles and purposes of SACs. The project adopts both the fundamental assumptions and approaches of learner belief studies in SLA and teacher cognition research in education. However, it examines neither learners nor teachers; instead, all the participants are SAC practitioners. Phase one of the study begins by surveying, through an online questionnaire, the different beliefs these practitioners have about self-access learning and SAC practice. This paper describes how the data was collected and analysed, as well as selecting a few interesting findings to highlight the value of conducting beliefs study on SAC experts. The findings reported in this paper need to be triangulated with follow up interviews (phase two) in order to construct a more accurate understanding of the beliefs held by the participants. Therefore, any conclusions or implications regarding the relationship between practitioners’ beliefs and SAC practice remain incomplete. Nevertheless, the findings from phase one provide an insightful preliminary picture of the diversity of both practice and practitioner from SACs across the world and open up a valuable avenue for further discussion.

Keywords: Beliefs research; self-access centres; professional practice; learner involvement

Background

This research was originally designed to investigate learners’ contributions to self-access centres (SACs). More specifically, it was intended as an exploration into the different ways in which learners were actively contributing to the administrative and pedagogic development of SACs. Working as a learning advisor in a SAC in Japan, I was looking for innovative ways of promoting learner input in our own centre. We had students working with us as ‘SAC staff’, assisting with various administrative duties, such as issuing material, liaising with SAC users, and restocking shelves. Additionally, we had an independent group of students who worked closely with our team of advisors to promote resources, events, and provide direct feedback on the SAC and its various services. I was curious about the nature of learners’ contributions in other centres, hoping to find ideas that could be adopted by our own SAC. The rationale was that while language education has shifted to a more learner-centered approach (reflected in the growing interest in self-access learning and learner autonomy – both of which argue for increased learner involvement and control throughout the language learning process), learner input in the day-to-day and big-picture management of SACs seemed neglected, or at the very least, limited. These limits were also partly reflected in the literature on self-access. While there are numerous studies on self-access learning (e.g. Cooker, 2010; Gardner & Miller, 1999; Gremmo & Riley, 1995; Sheerin, 1991), outside of a few investigations (Aston, 1993; Malcolm, 2004), there is little research examining learner involvement in SACs.

As I began my examination of both national and international centres, surveying scholarly articles, books, websites, reports, and any other sources that I could find, I almost immediately encountered complications, the first of which dealt with defining a SAC. Each institution I investigated had its own unique way of describing itself and some centres did not even refer to themselves as SACs, instead choosing labels such as independent learning centres (ILCs) or language learning resource centres (LLRCs). It became clear that in terms of SACs and SAC practice, there exists an array of mission statements, principles, descriptions of services, and outlines of goals and objectives. I was left with a highly eclectic picture of SACs from around the world. As I searched for common threads that could tie these centres together, I was struck by the variety of beliefs and personal theories that were governing the management of these centres and their approaches to language/ learning development. As a result, I made the decision to reshape and expand the project into an exploration of how experts’ beliefs about SACs affect policy and practice within the centres, including the management of learner involvement. While highly influenced by the work on learner beliefs and teacher cognition, this study is not an examination of either language learners’ or teachers’ thinking, but instead explores the beliefs and ideas of different SAC administration and practitioners. Adopting a beliefs approach helps manage some of the inherent challenges of evaluating behaviour solely from the perspective of an outside observer (Woods, 1996). In addition, foregrounding the participants’ understanding of their own practice in context will allow me to construct a more situation-specific description of the various facets involved in running a SAC.

In this paper I present the results of phase one of a two-phase study. Phase one included gathering and analysing responses to an online questionnaire surveying beliefs about a variety of topics directly related to SAC practice. Responses to the questionnaire were useful in illuminating the range of beliefs held by different SAC experts and in suggesting that this variety in perception influences the diversity found within centres around the world. I will use the results of phase one to prepare for a more in-depth investigation into what SAC experts believe about SACs. Phase two will use semi-structured interviews (structured around the results from phase one) to create a richer and more accurate understanding of the interplay between SAC experts’ beliefs and their centres’ practice. Phase two of the study has yet to be completed. Therefore, any conclusion or implications at this stage are tentative at best. A follow-up paper will include a more detailed description of the findings. Results discussed in this paper should be viewed only as a preliminary glance at the variety of beliefs held by SAC experts. Nevertheless, I believe that this glance is a valuable first step in a project that looks to create a clearer picture of SAC practice and examine how different approaches to self-access learning can be successful in meeting learners’ needs.

Survey of Belief Studies in Language Education: Origins, Evolution, and Influence

The sharp rise in interest in belief studies over the last three decades across educational contexts, specifically within language education, is largely the result of two major conceptual shifts: (1) the belief of contemporary psychology that thoughts and actions are intrinsically intertwined (Nespor, 1987; Schommer, 1990), and (2) the recognition of learners and teachers as active, thinking participants playing pivotal roles in the language learning process (Borg, 2006; Kalaja & Barcelos, 2006).

Belief studies focusing on learners have almost exclusively been conducted in the field of second language acquisition (SLA). Research in this area has been working toward an understanding of how beliefs about language learning influence learners’ approaches to, expectations of, and experiences with, language learning, i.e. learner behaviour (Wenden, 1986; Horowitz, 1999; Kalaja, 2006; Wenden, 1986). Although investigations of this nature remain varied, examining such phenomenon as the relationship between beliefs and anxiety (Young, 1991), proficiency (Mantle-Bromley, 1995), strategy use (Yang, 1999), and autonomy (Cotterall, 1999), they nevertheless all carry the underlying assumption that what learners believe about language and language education directly affects how they act.

In foreign and second language teacher cognition research (a subset of mainstream educational research), the emphasis switches from learner beliefs to teacher cognition.Defined as “what teachers know, believe, and think” (Borg, 2003, p.81) teacher cognition research explores the dynamic interplay between teachers’ mental lives (Walberg, 1977) (including their beliefs) and their teaching behaviour. More specifically, work in this area has investigated the relationship between teacher thinking and lesson planning (Woods, 1996), extensive reading (Macalister, 2010), and grammar instruction (Canh, 2012). A significant finding of this type of research, which carries strong implications for the current study, argues that teachers’ beliefs (cognition) and practice are not only mutually informing, but also that contextual factors play a major role in facilitating teachers’ ability to put their thoughts into action (Beach, 1994; Woods, 1996). In other words, the disparity observed between belief and behavior is often largely the result of context. Phase one of this study seems to support this finding, suggesting that the range of beliefs among practitioners is largely due to differences in context (institutional; cultural; situational – including professional responsibility; etc.). However, this suggestion needs to be properly triangulated through the in-depth interviews of phase two.

Belief studies connected to self-access learning have been previously conducted. Research in this particular area has examined learners’ readiness for autonomy (Cotterall, 1995), shifts in learner expectations about self-instructed learning (White, 1999) and the relationship between beliefs and action in a self-directed language learning context (Navarro & Thornton, 2011). However, up to this point there exists almost no work on how the beliefs of experts affect the practice of situation-specific institutions such as SACs. A belief study approach to SAC practice can offer valuable insight into the relationship between certain core factors, such as practitioner thinking and policy construction, or the way in which institutional context might facilitate (or inhibit) the implementation of pedagogical beliefs. However, examining the motivations behind the practices of SACs is an inherently complex project, not only because of the vast diversity of SACs, but more importantly because of the myriad of people involved in these centres – from learners, to teachers, to advisors, to managers, to centre directors, and higher up still – all of whom carry beliefs about learning, teaching, the roles and purposes of SACs and education. To a large extent these perceptions affect how the centres are run and the type of pedagogy that is implemented within them. This project offers but a glance into the world of self-access centres and the unique approaches to language learning they promote. Nevertheless, it is an important starting point.

The Study

Research questions

This study is interested in constructing a classification of SACs through a description of role, purpose and learner involvement. The following questions were used to guide the research:

- What do SAC experts believe about the roles and purposes of SACs?

- How are learners involved in the running of SACs?

- How is this involvement related to SAC experts’ beliefs?

Research outline

This is a two-phase study, with both a quantitative and qualitative component. Phase one involved constructing, piloting, and administering an online questionnaire. The questionnaire contains both closed and open-ended items. The closed-ended items provide a preliminary survey of experts’ beliefs about the roles and purposes of SACs. The open-ended items survey the nature of learner contributions to each SAC. Phase two involves interviewing the participants to get a more nuanced understanding of their responses to the questionnaire. Essentially, the interview data will help paint a more detailed picture of the relationship between SAC experts’ beliefs about self-access learning/ self-access centres and the actual practice that takes place within the various centres. This paper reports exclusively on the results of phase one of the study. While phase one of the study has produced interesting results (open and closed ended responses from an online questionnaire), the discussion remains limited in that the responses need to be triangulated with follow-up interviews to assess more accurately what the participants are communicating. Phase two of the study is underway but has yet to be completed.

Instrumentation: Questionnaire construction and pilot

In order to elicit (initial) responses about what the participants perceived the roles and purposes of SACs to be, and to gauge the nature of learners’ contributions across the surveyed SACs, I created a questionnaire to be administered online via SurveyMonkey. In addition to the 22 items directly related to the Roles and Purposes of SACs section, the questionnaire also contained:

(a) A Background Information section where participants provide information about themselves and their various SAC-related responsibilities (e.g. number of years working in a SAC; official job title; description of SAC duties; etc.)

(b) A Centre Profile section where participants describe their SAC according to logistical categories (e.g. name and location of centre; number of students visiting the centre; the extent to which students are required to visit the centre; language policy; etc.)

(c) A Learner Involvement section where participants describe the nature of learner contributions to the running of their centre. This section was mainly comprised of open-ended questions (e.g. In what capacity are learners involved in the running of your SAC?; What do you consider to be the benefits of having learners involved in the running of your SAC?; What do you consider to be some of the challenges of having learners involved in the running of your SAC?;Ideally, how would you like learners to be involved in your SAC?)

To construct the questionnaire, I began by examining the existing literature on self-access learning/ self-access centres. I evaluated statements and descriptions in the literature which defined and described what self-access learning was and what self-access centres do/ should do. I compiled a large list of items (over 50 statements) taken directly from the existing literature. I then looked for statements that overlapped (essentially saying the same thing) and collapsed them into single items. Finally, I took this comprehensive list of items and turned them into “SACs should…” statements, asking participants to select from Agree-Disagree responses. Once the initial draft of the questionnaire was created, I solicited feedback from colleagues in Japan and other self-access learning experts around the world. Eight individuals from five different SACs evaluated the initial items. Based on the feedback, I made revisions. Issues with the items and the corresponding revisions are described in the table below:

Table 1. List of Problems with Items and Corresponding Revisions

For the final part of the pilot, I asked three participants to take the online questionnaire. The three participants worked in affiliated SACs in Japan. Feedback was generally positive, as the questionnaire was deemed easy to understand and to complete. It took an average of 20 minutes to complete the online questionnaire. However, as with all closed-item questionnaires, there remained some issues with item ambiguity. This was most evident in section two, the Roles and Purposes ranking activity. In this section, participants were asked to read a total of 22 “SACs should…” statements (divided across four categories) and say whether they considered it an Essential, Preferable, or Not Necessary characteristic of a SAC (see Table 3 below). Because the participants had to choose only one response per item, and because there was no room for elaboration or any means of asking for clarification, this sometimes caused issues with accuracy (of responses) and understanding (of items). Particularly, all three of the pilot participants noted that there were instances where they wanted to add information to clarify or ‘contextualise’ their responses. They explained that some responses were very situation-specific and that this particular section of the questionnaire does not allow for a more detailed level of description. I expected this issue to arise, as it is a common problem with belief questionnaires (e.g. Sakui & Gaies, 1999). Phase two of the study is set up as a response to this problem, as participants will be given the opportunity to elaborate on their responses during the interviews, as well as to clarify any ambiguity with the items.

Participants

Thirty-nine responses were initially collected. However, one of the respondents failed to complete the questionnaire in its entirety. This data was not included in the final analysis. Therefore, a total of 38 responses (from 28 different institutions) were used in the phase one analysis. Appendix one describes the SACs surveyed according to ‘geographical location’ and ‘number of responses per location’. Appendix two lists all the ‘official job titles’ of the participants. In addition to ‘official job title’, participants were asked to describe their more inclusive ‘professional responsibilities’. While most of the participants were trained educators, there were also responses from ‘Centre Managers’ (Gardner & Miller, 2011, 2013) and ‘Centre Coordinators’, key figures in the day-to-day running of SACs who are not necessarily trained educators but do play pivotal roles in shaping SAC policy.

Table two presents the range of ‘responsibilities’ described by each of the participants.

Table 2. Description of Professional Responsibilities

The questionnaire’s participant/ SAC ‘background’ section also elicited information regarding the ‘age’ and ‘size’ of each institution, as well as the ‘student attendance policy’ at each SAC. Below is a summary of this information:

- Size of institutions surveyed ranged from 400 to over 20,000 students

- Centres were between less than 3 months and over 15 years old

- 61% reported mandatory SAC attendance

- 39% reported voluntary SAC attendance

Data collection

Phase one data was collected over a ten-month period. The first response was submitted in October 2011, the last in July 2012.

I used various methods to solicit responses. I asked colleagues at my own institution, I emailed colleagues from affiliated institutions around Japan, I researched SACs in Japan and contacted the ‘Centre Directors’ as well as ‘Centre Managers’ (typically the other professionals working in SACs who may or may not be trained educators), and I sent e-mail messages out to self-access and learner autonomy special interest groups (SIGs) that I was associated with. Unfortunately, my initial attempts to garner responses proved more difficult than initially anticipated. My goal was to have at least 50 centres from around the world, but four months after my initial requests (January 19, 2012), the response count was at 19. I did not get 20 responses until June 2012. I was a year into the project and was eager to push the number of responses up, so I asked colleagues, friends, and other ‘better-connected’ people for assistance (essentially asking them if they could ask people they knew to complete the questionnaire). I even started directly contacting SACs from around the world that I had previously investigated, sending unsolicited emails, describing the project and including a link to the survey. Over the next two months I was able to collect 19 more responses, bringing the total to 39 (However, as mentioned previously only 38 are included in the analysis).

Data analysis

For phase one of the project, two types of data were analysed. Descriptive statistics (simple percentages) were utilised for the ranking activity where all 38 participants responded to the following question: “From the list below, which do you consider Essential/ Preferable/ Not Necessary?” (Following this are, “SACs should…” prompts). Descriptive statistics were also used to gauge the different roles learners take on across the SACs. Finally, thematic analysis was used for the open-ended responses where participants commented on: the benefits and challenges of having students contributing to SACs, ways of managing these challenges, reasons for limited student involvement in their SAC, ideal ways which students could contribute to their SAC, and restraints on the implementation of these ideas. Thematic analysis offers a flexible yet systematic approach to qualitative data analysis involving the identification of themes or patterns of meaning through coding (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Researchers adopting this approach look for “commonalities, relationships, overarching patterns, theoretical constructs, or explanatory principles” (Lapadat, 2010, p. 926) within a data set.

Results and Discussion

Results

In this section, I first present a summary of the results from phase one. Next, I highlight some of the findings. Finally, I offer a brief discussion on the data and its implications.

As mentioned above, in the Roles and Purposes section of the questionnaire, participants completed a ranking exercise based on “SACs should…” statements. Tables three to six present a summary of these results (percentages/ number of responses).

Table 3. Beliefs about SAC Principles

Table 4. Beliefs about SACs and Access to Learning Resources

Table 5. Beliefs about SAC Support Structures

Table 6: Beliefs about SAC Materials

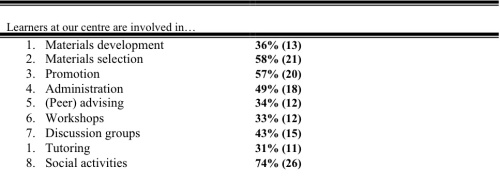

For the Learner Involvement section, participants were first asked to indicate the different ways in which learners are involved in their SAC according to a broad list of criteria. They were asked to answer Yes-No for the following question: Are learners at your institution involved in any of the following roles?

Table seven describes the various roles and responsibilities for learners in the different SACs.

Table 7. Description of Learners’ Roles and Responsibilities in SACs

After identifying the nature of student involvement in their SACs, participants then answered the following open-ended questions:

- What do you consider to be the benefits of having learners involved in the running of your SAC?

- What do you consider to be the challenges of having learners involved in the running of your SAC?

- How has your SAC dealt with/ does your SAC deal with these challenges?

- If learners are not involved, why do you think this is?

- Ideally, how would your SAC like learners to be involved?

- What constraints limit this involvement?

Due partly to space constraints, in this paper I will present a limited summary of the open-ended responses, focusing on two questions which explore practitioners’ beliefs about the benefits and challenges of having learners involved in the running of SACs. Another reason why the discussion of the findings is limited is because responses still need to be properly triangulated with follow up interviews. However, the responses from the questionnaire are able to show, quite clearly, some of the most important SAC issues amongst experts. In other words, the questionnaire data has made certain SAC-related issues salient, and as a result has opened up the opportunity for a larger, yet more focused discussion. Phase two (follow-up, semi-structured interviews) will include a detailed discussion of the items, including:

- The ways which different SACs manage the benefits and challenges of learner involvement

- The different factors limiting learner involvement

- How practitioners would ideally like learners to be involved in their centres

Summary of question one: Benefits of learner involvement in SACs

- ‘Serve as role models/ near peers’

- ‘Provide direct insight into learner perspectives’

- ‘Can accommodate learner needs more accurately’

- ‘Offer a sense of ownership’

- ‘Closer to the ideal of a SAC’

- ‘Cheaper than teachers’

- ‘More approachable than teachers’

- ‘Breaks boundaries between instructors & learners’

Summary of question two: Challenges of learner involvement in SACs

- ‘Getting institutional support’ (‘overcoming bureaucracy’)

- ‘Training learners’ (‘obvious limits to what learners can do – they are not trained educators’)

- ‘Motivating students to care enough to get involved’ (‘The concept of students taking control may be alien to the institution & the students.’)

- ‘Getting other staff (esp. native speakers) to tolerate inappropriate/ inaccurate language use’

- ‘Turnover’

- ‘Reliability and consistency of service’

- ‘Time consuming and costly’

- ‘Developing confidence and skills in the learners’

Discussion

Highlights of results

Below I have selected a few points to illustrate the value of conducting a beliefs investigation into SAC practice. As this paper deals exclusively with phase one of a larger project and only introduces some of the different beliefs held by practitioners across SACs, I felt I could be selective in the points I choose to highlight. Phase two of the project will analyse the responses in more depth. A follow-up paper will provide more rigorous description not only of the responses, but also of what the practitioners believed about the items they were responding to.

I selected item one because I found it interesting that of all the experts surveyed, only 32% believe it is essential for a SAC to adopt a principled approach to language learning. This number strikes me as extremely low (refer to Tables 3-6 for the full list of items). However, it is unclear if this means that SAC experts believe that a variety of pedagogical approaches may be more appropriate for SACs, or if there is yet to be a definitive approach that can encompass the complexity of self-access learning. Another possibility is that the item is itself ambiguous and participants were unsure of what exactly was being asked. This final possibility represents a major limitation of the responses and unfortunately, until follow up interviews are completed, it remains difficult to comment with more certainty. I selected item five because it deals directly with the initial, primary objective of the study. Item nine highlights an ongoing debate that has been taking place between SAC practitioners and classroom teachers. It is an issue that seems to have no definitive answer. However, I believe that the different opinions held on this topic offer all stakeholders involved valuable insights into how language learning generally, and self-access language learning specifically, is conceptualised and practiced. In addition, by raising awareness of the different beliefs regarding the relationship between self-access learning and classroom learning, we can come to a better understanding of our own beliefs, and realise that it is not necessarily a question of right and wrong, but more a question of what can work best for a particular context. I selected item 21 to discuss for similar reasons to item one. Again, I found it interesting that only 45% of SAC experts believed that it was essential to have materials specifically focused on developing learning skills as much as language skills. Section A below summarises responses to the Roles and Purposes portion of the questionnaire. Section B presents a brief commentary on the Learner Involvement section.

Section A: Roles and purposes

Item 1: SACs should adhere to a principled pedagogical approach. This item explored the idea of a supporting SAC practice with pedagogical principles. Only 32% of respondents said that a principled approach to language learning was essential. While much of the literature believes that SACs should aim to encourage and promote learner autonomy/ self-access learning (Benson & Voller, 1997; Gardner & Miller; 1999) this idea does not seem to be reflected in the responses. This might be due to the difficulties in defining autonomy or self-access learning (Gardner & Miller, 1999; Pemberton, Toogood, & Barfield, 2009), or it could be related to the lack of real theory in language education. It has been argued that there still exists no single theory of second language teaching (Woods, 1996) or of second language acquisition (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008). Nevertheless, having principles supporting the practices of SACs would offer both practitioners and learners some parameters with which to at least measure the effectiveness of what is taking place within the centre. This idea of a SAC’s pedagogical approach (and the principles that would assumedly underpin this approach) is an avenue worthy of further exploration. I intend to use phase two of this project to concentrate on this issue.

Item 5: SACs should involve learners in the running of the centre. This item is directly related to learners’ contributions to SACs. Only 34% of SAC experts said it is essential to involve learners. This is a surprising number again. Particularly since the field of language education has shifted toward more learner-centred pedagogy within language learning classrooms, even teachers’ and learners’ understanding of effective language learning practice now includes the practice of having learning activities ‘centred’ around the learner (Allwright, 1981). There may be various reasons to support these responses (without the interview data this remains highly speculative), but it is clear that from the participants sampled, SAC practice has not prioritised learner involvement. SACs still seem very much top-down institutions where teachers and educators control and direct how things are structured. This supports previous criticism which maintains that SACs continue to promote a system limiting user activity to the role of consumers of products selected and presented by others (Benson, as cited in Malcolm, 2004). Undoubtedly such a system, rather than fostering pro-active learner behaviour, perpetuates passivity from learners throughout the language learning process.

Item 9: SACs should provide access to learning opportunities independent of classroom work. This item examines the relationship between classroom learning and SAC activity. Eighty-two percent of respondents felt it was essential that the learning that takes place in a SAC not be (necessarily) connected with classroom language learning. This presents an interesting philosophical question that each SAC will presumably answer in its own way. It has been previously argued that to develop effective autonomy within learners, the classroom needs to play a central role (at least initially), bridging the gap between “public classroom activities and private learning activity” (Crabbe, 1993, p. 445). On the other hand, there is also a strong belief which supports the separation of self-access and classroom learning (Cooker, 2010; Dickinson, 1987). This view holds that the learning that takes place in self-access centres should be completely learner-led, whether this connects with what goes on in the classroom or not. Cases have been made for either argument, but what the responses show is that at some point, an ontological discussion about the nature of self-access learning would benefit all those involved in the running of the centre – including the learners.

Item 21: SACs should provide materials specifically designed for learner training (distinct from language skill materials). This item relates to beliefs about the types of SAC resources and material that need to be (or do not need to be) promoted in SACs. Forty-five percent of respondents believe it is essential that materials be offered to learners that help them develop skills necessary to become independent learners, materials that they can use to help them develop their own language learning skills. This seems basically to be saying that SACs need to offer learners self-access resources that learners can navigate with little to no expert assistance that will introduce them to principles and activities which help foster independent learning (Gardner & Miller, 1999; Jones, 1999). While the use of authentic texts is also seen as important in facilitating independent learning behaviour, both from an affective and practical perspective (Oxford & Nyikos, 1999), it would seem that one of the most significant challenges faced by SAC educators is finding (or creating) material that motivates learners to take more control over the actual learning process.

Section B: Learner involvement

The top three ways in which learners are involved in SACs are…

- social activities

- promotion of SAC services

- material selection

A cursory glance at these top three examples of learner involvement might suggest, as has been indicated above, that while there has been an obvious shift in language education to have learners more involved in classroom activities, SACs are still looking for ways of incorporating learners into more integral aspects of their management. While social activities, promotion, and material selection are important areas of SAC practice, it could be argued that learners in SACs have yet to transcend some of the more traditional barriers extended by language education. No doubt, with the learners’ best interests at heart, ownership of SACs – the kind of ownership that controls the ‘big-picture’ decisions – remains in the hands of the experts. Obviously, there are numerous challenges involved with having learners make moreimportant contributions to the running of SACs. Issues such as learner training, learner motivation/ investment, quality-control, as well as affecting ingrained attitudes, beliefs and expectations about education and the roles of teachers and learners would require significant amount of time and effort to accomplish. What has to be discussed, then, is whether or not it is worth it in the end – for all those involved – to have learners contributing in more influential ways.

Final Discussion and Conclusion

It is important to repeat that commenting explicitly on the results at this phase of the research remains speculative. Further exploration of the responses (in a more valid/ reliable manner) is needed to find out more clearly what the respondents were trying to communicate. Phase two of the research will follow up phase one with semi-structured interviews (the structure being provided by the questionnaire responses). This will add the rigor and description that the project needs to add significant value to the discussion on self-access learning and SAC practice. As Sakui and Gaies (1999) explain, there are limits to what can be learned about beliefs from questionnaire items, and interviews are a useful way of managing these limits as they help to “reveal beliefs which are not addressed in the questionnaire and to describe the reasons, sources, behavioural outcomes, and other dimensions of their beliefs” (Sakui & Gaies, 1999, p. 486)

What is clear however is that there is a range of ideas and beliefs about the particular categories and the items within the categories reflect an inherent diversity across SACs and the people who work in them – and this diversity is what I think, at this stage of discussion, is worth addressing. It is possible to use the responses from this project as a kind of sounding board for discussion within and amongst SAC practitioners. Exploring what the practitioners in our own centres believe and why, and moving onto an exploration of what other educators working in other SACs believe, will not only help SAC stakeholders gain new insights into particular areas of interest, but these discussions can help solidify practice in light of beliefs. Finally, when a better idea of some of these beliefs is established, SAC experts might then consider delving deeper to see how the effects of their beliefs and practices contribute to learner development. This is one area I believe all experts can agree on – that what we all should be focusing on is how what we believe and what we do impacts the learning outcomes that take place in our centres.

Notes on the contributor

Diego Navarro has been involved with language education for over 15 years. He holds an MA in applied linguistics from the University of Birmingham. Currently, he is working on a PhD at Victoria University of Wellington on the self-directed language learning endeavours of adult immigrants. His interests include language learning beyond the classroom, learner cognition, and language advising.

References

Allwright, R. L. (1981). What do we want teaching materials for? ELT journal, 36(1), 5-18. doi:10.1093/elt/36.1.5

Aston, G. (1993). The learner’s contribution to the self-access centre. ELT Journal, 47(3), 219-227. doi:10.1093/elt/47.3.219

Beach, S. A. (1994). Teacher’s theories and classroom practice: Beliefs, knowledge, or context? Reading Psychology, 15(3), 189−96.

Benson, P., & Voller, P. (Eds.). (1997). Autonomy and independence in language learning. Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Borg, S. (2003). Teacher cognition in language teaching: A review of research on what language teachers think, know, believe, and do. Language Teaching, 36(2), 81-109. doi:10.1017/S0261444803001903

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition and language education: Research and practice. London, UK: Continuum.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Canh, L. V. (2012). Interviews. In R. Barnard & A. Burns (Eds.), Researching language teacher cognition and practice: International case studies (pp. 90-108). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Cooker, L. (2010). Some self-access principles. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(1), 5-9.

Cotterall, S. (1995) Readiness for autonomy: Investigating learner beliefs. System, 23(2), 195-205. doi:10.1016/0346-251X(95)00008-8

Cotterall, S. (1999). Key variables in language learning: What do learners believe about them? System, 27(4), 493-513. doi:10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00047-0

Crabbe, D. (1993). Fostering autonomy from within the classroom: The teacher’s responsibility. System, 21(4), 443-452. doi:10.1016/0346-251X(93)90056-M

Dickinson, L. (1987). Self-instruction in language learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (2011). Managing self-access language learning: Principles and practice. System, 39(1), 78-89. doi:10.1016/j.system.2011.01.010

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (2013). Self-access managers: An emerging community of practice. System, 41(3), 817-828. doi:10.1016/j.system.2013.08.003

Gremmo, M.-J., & Riley, P. (1995). Autonomy, self-direction and self-access in language teaching and learning: The history of an idea. System, 23(2), 151-164. doi:10.1016/0346-251X(95)00002-2

Horowitz, E. K. (1999). Cultural and situational influences on foreign language learners’ beliefs about language learning: A review of BALLI studies. System, 27(4), 557–576. doi:10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00050-0.

Jones, F. R. (1993). Beyond the fringe: A framework for assessing teach-yourself materials for ab initio English-speaking learners. System, 21(4), 453-469. doi:10.1016/0346-251X(93)90057-N

Kalaja, P. (2006). Research on students’ beliefs about SLA within a discursive approach. In P. Kalaja & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches (pp. 87-108). New York, NY: Springer.

Kalaja, P., & Barcelos, A. M. F. (2006). Introduction. In P. Kalaja & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches (pp. 1-4). New York, NY: Springer.

Lapadat, J. C. (2010). Thematic analysis. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of case study research (pp. 926-928). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Larsen-Freeman, D., & Cameron, L. (2008). Complex systems and applied linguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Macalister, J. (2010). Investigating teacher attitudes to extensive reading practices in higher education: Why isn’t everyone doing it? RELC Journal, 41(1), 59-75. doi:10.1177/0033688210362609

Malcolm, D. (2004). Why should learners contribute to the self-access centre? ELT Journal, 58(4), 346-354. doi:10.1093/elt/58.4.346

Mantle-Bromley, C. (1995). Positive attitudes and realistic beliefs: Links to proficiency. The Modern Language Journal, 79(3), 372-386. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1995.tb01114.x

Navarro, D., & Thornton, K. (2011). Investigating the relationship between belief and action in self-directed language learning. System, 39(3), 290-301. doi:10.1016/j.system.2011.07.002.

Nespor, J. (1987). The role of beliefs in the practice of teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19(4), 317-328. doi:10.1080/0022027870190403

Oxford, R., & Nyikos, M. (1989). Variables affecting choice of language learning strategies by university students. The Modern Language Journal, 73(3), 291-300. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1989.tb06367.x

Pemberton, R., Toogood, S., & Barfield, A. (Eds.). (2009). Maintaining control: Autonomy and language. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Sakui, K., & Gaies, S. J. (1999). Investigating Japanese learners’ beliefs about language learning. System, 27(4), 473-492. doi:10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00046-9

Schommer, M. (1990). Effects of beliefs about the nature of knowledge on comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(3), 498-504. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.82.3.498

Sheerin, S. (1991). Self-access. Language Teaching, 24(3), 143-157. doi:10.1017/S0261444800006315

Walberg, H. J. (1977). Decision and perception: New constructs for research on teaching effects. Cambridge Journal of Education, 7(1), 33-39. doi:10.1080/0305764770070105

Wenden, A (1986). What do second-language learners know about their language learning? A second look at retrospective accounts. Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 186-205. doi:10.1093/applin/7.2.186

White, C. (1999). Expectations and emergent beliefs of self-instructed language learners. System, 27(4), 443-457. doi:10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00044-5

Woods, D. (1996). Teacher cognition in language teaching: Beliefs, decision-making and classroom practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Yang, N.-D. (1999). The relationship between EFL learners’ beliefs and learning strategy use. System, 27(4), 515-535. doi:10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00048-2

Young, D. J. (1991). Creating a low anxiety environment: What does the language research suggest? Modern Language Journal, 75(4), 426-436. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1991.tb05378.x

Appendices

Appendix A

Name and Location of SAC

*21 responses from SACs in Japan; 5 responses from SACs in Hong Kong; 3 responses from SACs in New Zealand; 6 Responses from SACs in Europe; 3 Responses from SACs in Mexico. Cities listed multiple times mean indicate a different institution.

Appendix B

Job Description