Christine Rosalia, Hunter College, City University of New York, USA

Rosalia, C. (2013). So you want to start a peer online writing center? Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(1), 17-42.

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to share lessons learned in setting up three different peer online writing centers in three different contexts (EFL, Generation 1.5, and ESL). In each center the focus was on the language learner as a peer online writing advisor and their needs in maintaining centers “for and by” learners. Technology affordances and constraints for local contexts, which promote learner autonomy, are analyzed. The open-source platforms (Moodle, Drupal, and Google Apps) are compared in terms of usability for peer writing center work, particularly centers where groups co-construct feedback for writers, asynchronously. This paper is useful for readers who would like a head start or deeper understanding of potential logistics and decision-making involved in establishing a peer online writing center within coursework and/or a self-access learning center.

Keywords: peer feedback, open source technologies, online learning, second language writing, online writing center

The benefits of peer learning for student writers has a long and well documented history, with research evidence of success across higher education (Falchikov, 2005; Topping, 2003). In the United States, Whitman (1988) summarized systematic benefits of peers teaching peers for students, teachers, and institutions. They found that students gained “a more active role in the learning process” when engaged in peer teaching because “reviewing and organizing material as a ‘teacher’ was more cognitively rigorous than simply receiving it as a ‘student’ alone—to teach was to learn twice” (p. 5). Other benefits for peer review[1], often cited specifically for language learners, are that the giver of feedback gains self-evaluation skills for assessing their own writing (Chien, 2002) and improves their own writing proficiency (Lundstrom & Baker, 2009), especially their appreciation of audience (Tuzi, 2004). Improvements have been documented even in cases when the peer reviews a paper written above their current writing proficiency (Marcus, 1984).

For classroom language teachers, the facilitation of peer review can be a rich and regenerating resource. With proper student training and structure, adding peer review to a class increases the amount and promptness of individualized instruction to writers. For example, in an efficient thirty minutes with a class of 30 writers a teacher can circulate the classroom making sure 30 writers get and give feedback on the ideas of their essay. In large classrooms, as Laurillard (2008) notes, each student would normally get as little as 5 minutes of individualized teacher attention per week. However, in a “flipped”[2] reading and writing classroom, in which a teacher sets up “reciprocal teaching” activities that include peer review, he or she is circulating around the room refining (and learning from) peer dialogues. The teacher is using peer feedback to notice information about the student reviewer and writer simultaneously (Paulus, 1999). How does the student use metacognitive strategies? How is the student summarizing theirs and others’ texts? How are they questioning, clarifying, and predicting as they read and write? Do they find one role–being a reviewer or the reviewee–easier? Is the dialogue real, encouraging, helpful, and productive?

Peer dialogue and its written artifacts are not only very telling for assessing metacognitive literacy skills. Teachers might also use the artifacts of peer review to understand ways to innovate and reset their own pedagogy. One example of this can be seen in Black’s (2005) study of English language learners who formed a homegrown fan fiction network online, outside of formal school. She observed the “stickiness” of these writers’ online feedback: when an author left feedback on another author’s blog, the two authors were automatically “linked”. Once linked, Black observed her reluctant second language writers thrive in a professionalized community of writers, where writers gave each other moral support and concrete resources, such as story skeletons. She found that writers using socially mediated technology gained voice–became more autonomous multilingual writers–and it inspired her to think of why this productivity so sharply contrasted with these writers’ school experiences. We may take blogging as a writer/audience tool for granted today, but in the early 2000s, the time of Black’s research, paying attention to this peer learning (the stickiness of blogs) meant a teacher gleaning pioneering teaching techniques from the students she might have expected learning from the least. Capturing ideas for professional development from students’ peer learning may be particularly important for teachers of academic writing who may not have taken course work in the teaching of writing during their training. Second language scholars, still today, cite the dearth of professional preparation of writing teachers (Leki, Cumming, & Silva, 2006; Ortmeier-Hooper & Enright, 2011).

A keen eye on peer tutoring and learning is not only helpful to teachers, but also to institutions. When students work as ‘teachers’ they consider teaching as a future profession; thus, peer tutoring serves as a form of informed teacher recruitment (Whitman, 1988), with many writing center peer tutors becoming teachers (Gillespie & Lerner, 2007). However, teacher recruitment is not the limit of peer tutoring’s effect. One research project by Hughes, Gillespie, & Kail (2010) looked at 126 former peer tutors across three universities who had had their peer tutoring experience in the 1980s (24%), 1990s (33.6%), or 2000s (42.4%), and who later had careers in and outside of education. This study found that peer tutoring gave peer tutors “a new relationship with writing; analytical power; a listening presence; skills, values and abilities vital in their professions; skills, values and abilities vital in families and in relationships; earned confidence in themselves; and a deeper understanding of and commitment to collaborative learning” (Hughes et al., 2010, p. 14).

Peer tutoring by multilinguals in centers for English writing

While writing centers have been normalized on many college campuses, it is relatively new that peer tutors be English as a Foreign or Additional Language (EFL or EAL) writers and tutors. Some reasons for a lack of inclusion of EAL peers tutors in writing centers (in English and non-English dominant countries) include: lack of exposure or acceptance of writing center pedagogy; language teachers already successfully grappling with peer review in their action-based research classrooms (Min, 2005; Hu, 2005); insufficient student readiness for learner autonomy (Cotterall, 1995), and lack of financial, institutional, and/or philosophical structure for supporting peer tutors (Mynard & Almarzouqi, 2006). In addition, in some contexts there may still be perceptions by students (and some teachers) that language learners do not want peer review by nonnative speakers because of a privileging of the native speaker (Kramsch, 1997) or because of previous classroom experiences that did not successfully use peer review in tandem with teacher and self-assessment (Nelson & Carson, 2006). Teachers and students might worry that the writing center experience would be a mere replication of classroom peer feedback, a negative experience, or, if outside the classroom, something difficult for self-access learning centers to consistently fund. Indeed, Bedore and O’Sullivan (2011) used multiple research methods (surveys, focus groups, and follow-up interviews with students, novice teachers, teacher educators, and a program director) to document how at one university there was a “complicated” and “deep-rooted ambivalence” toward peer review, despite appreciation of its potential benefits. Confidence and commitment to peer review correlated with one’s teaching experience. As one research participant explained:

I think we all struggle… [H]ow do we teach peer review? How do we model it? Not just, why it’s useful, but how to actually do it. I mean, we’ve had so much trouble finding an effective way to teach it. (Bedore & O’Sullivan, 2011, p. 11)

Benefits of online peer writing centers

Online peer writing centers offer several ways to combat logistical, philosophical and/or training issues related to peer tutoring for and by language learners. Affordances include the possibility for the exchange of papers to occur outside the classroom, the extension of time for response (self-, peer, and teacher response) and the allowance of different kinds of anonymity (i.e., “blinding” of reviewers, authors, and/or the use of aliases), all of which are important if learners and teachers lack confidence in facilitating peer feedback. A common issue undermining confidence includes language learners’ (as tutees and tutors) not having enough metacognitive awareness or prior experience with English metalanguage to discuss writing deeply and at various levels. Tutors worry about how to respond to a writer who may ask a question such as “How is my grammar?” (when the paper they are reading has many categories of grammatical error) or “How are my prepositions?” (when the tutor feels the writer’s paper has more important content-related weaknesses that ought to be addressed first). Because online written feedback given asynchronously is automatically recorded, these records can be used by writing center directors or teachers as learning objects. They can be used for recursive training on the doing and facilitating of peer feedback. Therefore, in situations where teachers and/or learners lack confidence, or simply want to exploit the interaction for more learning, an online record of the process (Hounsell, 2007) is helpful. Unlike in face-to-face centers, if a tutor wants to “observe” another tutor as a way of professionally developing, they do not need to schedule an observation: the “evidence” they want to observe is already available to them. Staff of an online writing center automatically share experiences, and can “data-mine” for feedback they wish to emulate, or further discuss.

Choosing the Technology, Work Protocols, and Mission for Your Center

The technology necessary for an online peer writing center depends on the needs, resources, and quality of feedback hoped for by its constituent users. In the three peer online writing centers this article describes, peer advisors would write feedback and a teacher would lead a discussion (give feedback-on-feedback) of how well the feedback:

(1) capitalized on the writer’s strength(s),

(2) paid attention to affect,

(3) was organized so that it was noticeable and salient on a computer screen,

(4) fostered more learning,

(5) modeled good language use, and

(6) considered multiple self-assessments (the writer’s and the peer advisors’)

In each project, facilitating peer feedback to reach these six criteria was purposefully designed to improve the peer advisors’ own writing, self-regulation, and ability to give quality feedback to writers (Rosalia & Llosa, 2009). It was important in all projects that feedback was not just a product sent to a writer, like putting a coin into the feedback machine and waiting for feedback to come out. Though providing quality feedback was important, equally important was the process of negotiation, for and with peer advisors. Therefore, in each system there were three readers for every submission: reader 1, reader 2, and a facilitator that helped to check that together reader 1 and reader 2 wrote quality feedback. In other words, a facilitator made sure that the finished feedback satisfied the six criteria, but also that in the process of feedback generation, that the peer advisors wrote notes to each other. Instances of notes were about where one reader had left off and had expected the next reader to continue, or about what one reader assessed the quality of the feedback to, currently, be. A recurring thread was making sure peer feedback (re)triggered and sustained self-assessment (theirs and the writer center client’s) and the use of teachers–as means, and as resources, not as ends (Ciekanski, 2007). A writer’s own self-assessment was considered to be a critical feature of a good online peer writing center because it signaled the extent to which the writer was able to self-monitor and demonstrate metacognitive awareness.

Comparisons of Technologies Used in Support of Centers

Given that sustainability of any online writing center depends on its ability to fund or sustain itself, open-source and free technologies were used in all the settings of the centers discussed. Limited budgets were used to pay for staff, when available. In all of the settings described here, a writing center director was present, but this may not need to be the case in all contexts. Table 1 compares peer tutors, their contexts, technologies chosen, level of administrative control given to the writing center director (e.g., ability to directly make user accounts or customize users’ experiences), and how writers submitted writing for feedback. While one center paid peer tutors, two used a classroom model, at first, in which students did peer tutoring as a course requirement, and later competed for a limited number of “paid” positions. Peer tutoring as an initial course requirement can serve two purposes: it can be used as a “pilot” to document to funders that a center is worth implementing, and, second, as unpaid training. As such, both the peer tutor(s) and the director of a center are able to see if online peer tutoring is a good fit.

The author recognizes, too deeply, the struggle for funding to pay peer tutors (or a director). While a program might not be able to fund peer tutors, some creative solutions used include winning funds to buy peer tutors’ textbooks for courses in their major, asking for semester stipends for tutors (rather than hourly pay), and providing tutors one-on-one tutoring on their own homework, as a form of bartering. One-on-one tutoring, while time-consuming for a director / teacher, is rewarding in that tutors’ homework is often the same kinds of assignments they would later see submitted to a center. Finally, while paying students for the painstaking work of providing quality online feedback to writing center clients is still the best option, when interviewed about pay issues, tutors have often said, after the experience, that money was not the key motivator for them. Indeed, online user logs and records consistently show that tutors work beyond the time they have been paid for–a clear indicator that the work is engaging enough in its own right. However, part of valuing peer feedback is paying tutors and a director for their time and growing expertise. Despite positive research in support of peer tutoring (e.g., Hughes et al., 2010), funding will likely always be an issue. Documenting the positive and lasting benefits of peer tutoring can only help both tutors and administrators find creative solutions for a valuable service. (See Neal Lerner’s work, especially Lerner (2001), for more on writing center assessment issues).

Table 1. Comparison of Peer Online Writing Centers in Three Contexts

Contexts 1, 2, and 3 were, in order: a center for EFL undergraduate writers in Japan, a center for an intact undergraduate class of multilingual computer systems majors in the United States, and a center for ESL pre-college and community college writers, also in the United States. In order to promote writer learner autonomy, feedback began and ended in each of these systems with a writer’s help-request. That is, in order to submit writing for feedback, writers were required to self-assess their own writing and complete a help-request.

Peer tutors were then to address this help-request, even if it did not match what they felt should be a priority in making the writing better. They were also to do this even if the question was vague, such as the always popular: “How is my writing?”.

Context 2 was unlike the other two contexts in that, initially, the peer advisors had a dual role of being both peer advisors and writers who submitted their own writing in the online system. They were required to do this as part of three classroom assignments. Later, students in Context 2 applied and competed for five limited paid positions (one-time semester stipends). These five tutored a composition class on assignments similar to the ones they had just completed in their composition class.

It is important to note that in each center, peer advisors, over time, chose the way to present their online center. In the EFL context, the peer advisors chose a mascot and splash page as their gateway for submissions, whereas when peer advisors were Generation 1.5 (Roberge, Siegal, & Harklau, 2009) computer systems’ majors, they felt their peers would prefer to go directly into a content management interface. In the American ESL project, where Google Docs were being used heavily in higher education, peer advisors focused on integrating their online center into what users were already using. Likewise, this last group, instead of recommending resources to writers via a discussion board (as in Contexts 1 and 2), the ESL group experimented with a Facebook page, again using tools that already had currency in their context.

Figure 1. Center for EFL undergraduates: Splash page >> Submission self-select page

Figure 2. Center for undergraduate generation 1.5 computer systems majors: Drupal login page>> “submission central” dashboard for submitting and reviewing peer writing

Figure 3. Center for ESL pre-college writers: Gmail invitation to share a Google Doc >> writer opens up their Google Drive

The author’s experience in directing these centers (Context 1 for 4 years, Context 2 for 1.5 years, Context 3, the newest, for 1 year), is that it is not so important which technology or bundle of technologies the peer advisors use, but rather, that peer advisors are active participants in the initial and the continued choosing of technological solutions.

Shared decision-making

Shared decision-making is particularly important in deciding how peer advisors and staff work together to co-construct feedback to writers: peer advisors need to feel comfortable in how they work together through technology because the process of giving feedback requires complex layered readings of screen text and dynamic “feedback-on-feedback.” Figure 4, is a sample of complex layered reading and talk about feedback between three peer advisors in Context 3. Reader 1 used blue font to show her voice (and says to the writer: “this is one of the best essays we have worked on in the writing center, so far.”), Reader 2 used orange font, and Reader 3 (the “Facilitator”) used green font. The writing center director used a comment bubble to check in with peer advisors about the overall process.

Figure 4. Sample colored in-text feedback-on-feedback among three peer advisors, plus writing center director comment bubble on overall process

When this process is collaborative, I have seen comments like the following in Figure 5 from peer advisors about their work:

Figure 5. Peer advisor open reflection regarding state of writing center work

Note that Appendix 1 shows the finished feedback that this advisor refers to. While this reflection on how technology trials are going (using two Google App logins and a third Facebook login) is mixed, there is no question that the peer advisor is involved and positive about where she and her colleagues are going in evaluating technologies for their center. The post is open and has a spirit of collaborative experimentation.

An important consideration in setting up an online peer tutoring system is a belief in a few fundamental values: that students’ words are their own and not to be appropriated; that the role of a tutor is to be respectful of a peer’s writing (a fellow tutor’s or the writer’s), no matter what the level of ability; that co-construction of feedback is beneficial because it requires negotiation of the degree and direction of feedback to the writer; and that the end goal of peer tutoring is not to “fix” a peer’s essay (the “put developing essay in, get perfect essay out” model), but to promote learner autonomy with attention to affect and camaraderie.

Because staff of an online center do most of their communication mediated by technology and the written word, sensitivity to writing, response, and protocol are critical. This is precisely what helps improve peer advisors writing skills, but it takes some practice for new peer advisors depending on their readiness for learner autonomy (Cotterall, 1995) and experience collaboratively editing the same text online. For example, in a chain of feedback production, if a second reader does not give a rationale or note changes they made to a first reader’s text, the third reader will likely be confused. Consider, in Figure 6, how a third reader would need to reconstruct what is so far given to a writer, Joyce (pseudonym), to be helpful. For orientation, in Figure 6, we see the work of Taro, a peer advisor still in training, who had confused other writing center staff by logging into the center outside his assigned hours, and then working on a submission as if he were the only constructor of feedback. Unlike the first reader of the submission (her work is in blue font and/or underlined) who addresses other writing center staff with a “Hi everyone”, Taro does not write anything to the group, nor does he respond to the first reader’s request for feedback on her feedback. She had worried if her feedback had been “too self-centered”, helped “too much”, or had addressed the writer’s request for “verb tense” help. As a second reader, Taro (whose work is in italics and/or red font) did not respond to his colleague’s opening dialogical remarks or feedback assessment. Additionally, Taro appropriates the writer’s text (the bold and black text) giving a novice and, perhaps, unhelpful reason for revision: he writes that the writer should use his version, as it is “more smooth”. Here is the post verbatim:

Figure 6. Sample of Taro’s lack of negotiation with other peer tutors during online advice co-construction

Taro was not used to a layered collaborative approach to co-constructing feedback. Still in his first weeks of training, this approach was understandably new to him. One can see the difference between his response to a writer’s work, and the response of the first reader, a peer advisor with more experience. Though still with weaknesses, the first reader’s advice to Joyce considers “audience” and a conflict in tone between the writer saying “great points” about the subject of the essay (a loved former high school teacher) and then “terrible things.” It can be inferred that this is why she worried that she should say more to the writer about “word choice.” There is some indication that Taro internalized some of the first reader’s advice not only because he uses the subject-pronoun “we”, but also, because his revision uses the first reader’s suggestion to adjust “word choice” or to better explain the “terrible things” sentence. However at this stage of his collaborative writing development, Taro is not showing the higher order skill of providing feedback on feedback or eliciting critique of his work. As a second reader, rather than improving Reader 1’s feedback, Taro brings more confusion to the text. Nor is his feedback convincingly promoting Joyce’s learner autonomy. His “please challenge” will likely be ineffective because of its vagueness.

When asked about working outside his assigned time, Taro used metaphors of needing to get a product back out to a customer: “Process talk” among staff meant less to him than finishing many submissions in a short time. Thoughts about whether he had been appropriating a writer’s words instead of addressing their questions about their own writing, or his responsibility to respond to colleagues’ questions about the quality of their feedback, in his mind, slowed production down. Defensive of his more authoritative style for feedback giving, Taro explained, verbatim:

I wonder if my style will not fit to the students [sic] expectation. The posted essay contents are very friendly and they are contents to be written in the e-mail such as on the mobile phone and/or home PC. If the Prof. accept the such [sic] form (style) of essay or letter, I am a not right person to touch to their posted essay.

To the outside reader, it may be hard to understand that Taro is talking about peer advisor work. In contrast to the reflection on advising work of the peer advisor in Figure 5, Taro does not feel shared ownership of the co-construction process, yet. After just initial peer training, he was not ready to give up the traditional hierarchy of schooling roles—and some learners never are. The “students” Taro refers to are his co-workers who got angry with him for working outside of his assigned time (it meant submissions they were to have worked on had already been taken by Taro). The “essay” Taro refers to is the feedback post, and “the Prof” is the writing center director, who attempted to discuss word by word Taro’s advice to the writing center client, Joyce. More training or group discussion was needed to address Taro’s conflicts more directly and clearly. This is why it is recommended to build in regular face-to-face meetings with staff. Initially, writing under the micro lens of shared online forums, even if one uses anonymous aliases, can be uncomfortable. Taro was not expecting so much attention to be drawn to how he was giving feedback or to give so much attention to others’ feedback. Likewise older peer advisors were used to work in a certain way. A risk that peer feedback systems sometimes take is the time that is required for a group to define, understand, and refine their collaboration. A group may need up to one semester to find their working grove–another reason for piloting peer advisor work carefully.

Because all communication occurs through writing, workflow protocols in an online writing center may be more important than that of a face-to-face center. Appendix 2 shows the workflow systems co-designed with peer advisors in the respective centers. As explained earlier, an affordance of an online center is that feedback to writers is co-constructed. In an online center based upon a philosophy of group co-construction, peer tutors are interdependent, unlike in a face-to-face center where a peer tutor works with a writer in a one-to-one exchange. Taro’s not following protocol and not responding to Reader 1’s call for feedback on her feedback (Figure 6), meant the third reader had more work to do because Taro had not drafted feedback with Reader 1. The third reader or facilitator would need to write back to Taro and Reader 1 separately (giving each feedback about the quality of what was written individually) and still make choices about condensing and synthesizing final feedback to the writer. Protocols and communicating through writing are paramount, and are good pressures on peer tutors, if they see them as opportunities for refining both their applied technology and writing skills. The absence of physical context presents an authentic communicative context in which clear communication through writing becomes the need driving peer tutors’ efforts.

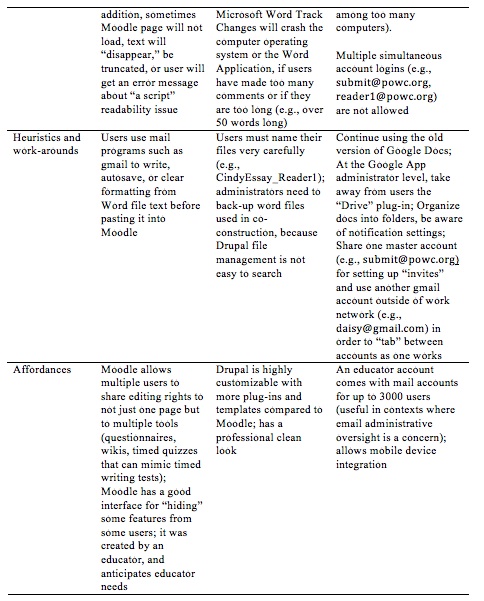

Recommendations. Having peer advisors develop their center’s work manuals and protocols, themselves, is one way to make sure that a peer online writing center is by and for peer tutors. Because it is common and practical for writing centers to have peer tutors with varying amounts of expertise, older tutors can initially lead newer tutors in this work. When writing protocols (and revisiting them over time), peer tutors internalize and personalize a complex process. Innovation is spurred because in their explaining and negotiating protocols with other members, better ways of working are often realized. Table 2 shows how peer advisors in each center were first shown a method, which after one semester they could elect to change. First using one system helped them to later be in a position of comparing and appreciating other technologies. Thus, for example, in Center 1 peer advisors experimented with online chat before deciding to use asynchronous discussion boards. In Center 2, peer advisors first used the Drupal system as a requirement for their freshmen composition class, but later altered the system to include Skype chat for managing who was reading which submission. In Center 3, peer advisors had first used Moodle and then chose Google Apps. In each case, it was not the technology chosen that was important, but that choices were informed by experience and feelings of ownership. In all three of these centers, weekly face-to-face meetings were led or co-organized by peer advisors to discuss work that the staff had done the previous week together online.

Table 2. Technology-based Comparison of Peer Advisor Management Across Centers

As Table 2 demonstrates, especially for “heuristics and work-arounds”, using open source or free technologies necessitates regular communication among staff. Choice, flexibility, and problem solving are indigenous to peer writing center practice.

Conclusions

At question in this paper was not whether online peer tutoring works or not. In the author’s experience, if peer tutors decide how, are actively involved, listened to, and supported by teachers and writing center directors, the benefits are rich and can be shared by many constituents. Instead, at question is what an online peer writing center might look like for learners in your setting. This paper has reviewed different tools used in different contexts (to give you a head start) and encourage you to focus on (1) how learners will manage technology choices, and (2) become resilient to the “messiness” inherent in choosing tools and protocols to take charge of their own learning. The need for regular revisits by the staff of work protocols is emphasized because the main affordance of an online writing center is also its challenge: peer tutors use technology and writing to communicate and to be interdependent. This approach argues for the co-construction of peer feedback facilitated by a teacher and later, as the center grows, with senior peer advisors. Co-constructing online feedback requires layered readings of feedback-on-feedback. Groups learn how to do this together, over time, and with much collaboration. Regular face-to-face meetings with staff make possible a cohesive online life. So you want to start an online writing center? Make sure it is built upon interdependence, a commitment to social autonomy, and collaboration over time.

Notes on the contributor

Christine Rosalia is an Assistant Professor of TESOL for medical assistant classes online. Her research interests include second language writing, educational technology, and the fostering of self-regulated learning among language learners. She is currently applying her experience directing online writing centers to her work with NYC language teachers.

Appendices

Please refer to the PDF version

References

Bedore, P., & O’Sullivan, B. (2011). Addressing instructor ambivalence about peer review and self-assessment. WPA Journal, 34(2), 11-36.

Black, R. W. (2005). Access and affiliation: The literacy and composition practices of English language learners in an online fanfiction community. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 49(2), 118-128. doi:10.1598/JAAL.49.2.4

Chien, C. L. (2002). Strategy and self-regulation instruction as contributors to improving students’ cognitive model in an ESL program. English for Specific Purposes, 21(3), 261-289. doi:10.1016/S0889-4906(01)00008-4

Ciekanski, M. (2007). Fostering learner autonomy: Power and reciprocity in the relationship between language learner and language learning adviser. Cambridge Journal of Education, 37(2), 111-127. doi:10.1080/03057640601179442

Cotterall, S. (1995). Readiness for autonomy: Investigating learner beliefs. System, 23(2), 195-205. doi:10.1016/0346-251X(95)00008-8

Falchikov, N. (2005). Improving assessment through student involvement: Practical solutions for aiding learning in higher and further education. New York, NY: Routledge Falmer.

Hounsell, D. (2007). Towards more sustainable feedback to students. In D. Boud & N. Falchikov (Eds.), Rethinking assessment in higher education: Learning for the longer term (pp. 101-113). New York, NY: Routledge.

Hu, G. (2005). Using peer review with Chinese ESL student writers. Language Teaching Research, 9(3), 321-342. doi:10.1191/1362168805lr169oa

Hughes, B., Gillespie, P., & Kail, H. (2010). What they take with them: Findings from the peer writing tutor alumni research project. Writing Center Journal, 30(2), 12-46.

Gillespie, P. & Lerner, N. (2007). Longman guide to peer tutoring (second edition). New York, NY: Longman.

Kramsch, C. (1997). The privilege of the nonnative speaker. PMLA, 112(3), 359-369.

Laurillard, D. (2008, April). Digital technologies and their role in achieving our ambitions for education. Professorial lecture conducted at the Institute of Education, University of London, UK. Retrieved from http://eprints.ioe.ac.uk/628/1/Laurillard2008Digital_technologies.pdf

Leki, I., Cumming, A., & Silva, T. (2006). Second-language composition teaching and learning. In P. Smagorinksy (Ed.), Research on composition: Multiple perspectives on two decades of change. (pp. 141-170). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Lerner, N. (2001). Choosing beans wisely. The Writing Center Newsletter, 26(1), 1-5.

Lundstrom, K., & Baker, W. (2009). To give is better than to receive: The benefits of peer review to the reviewer’s own writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(1), 30-43. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2008.06.002

Marcus, H. (1984). The writing center: Peer tutoring in a supportive setting. English Journal, 73(5), 66-67. doi:10.2307/816981

Min, H-T. (2005). Training students to become successful peer reviewers. System, 33(2), 293-308. doi:10.1016/j.system.2004.11.003

Mynard, J., & Almarzouqi, I. (2006). Investigating peer tutoring. ELT Journal, 60(1), 13-22. doi:10.1093/elt/cci077

Nelson, G., & Carson, J. (2006). Cultural issues in peer response: Revisiting “culture”. In K. Hyland & F. Hyland (Eds.), Feedback in second language writing: Context and issues (pp. 42-59). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ortmeier-Hooper, C., & Enright, K. A. (2011). Mapping new territory: Toward an understanding of adolescent L2 writers and writing in US contexts. Journal of Second Language Writing, 20(3), 167-181. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2011.05.002

Paulus, T. M. (1999). The effect of peer and teacher feedback on student writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 8(3), 265-289. doi:10.1016/S1060-3743(99)80117-9

Roberge, M, Siegal, M., & Harklau, L. (Eds.). (2009). Generation 1.5 in college composition: Teaching academic writing to U.S.-educated learners of ESL. New York, NY: Routledge.

Rosalia, C., & Llosa, L. (2009). Assessing the quality of online peer feedback in L2 writing. In R. de Cássia Veiga Marriott & P. Lupion Torres (Eds.), Handbook of research on e-learning methodologies for language acquisition (pp. 322-338). Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference.

Topping, K. (2003). Self and peer assessment in school and university: Reliability, validity and utility. Innovation and Change in Professional Education, 1, 55-87. doi:10.1007/0-306-48125-1_4

Tuzi, F. (2004). The impact of e-feedback on the revisions of L2 writers in an academic writing course. Computers and Composition, 21(2), 217-235. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2004.02.003

Whitman, N. A. (1988). Peer teaching: To teach is to learn twice (Report No. 4). Washington, DC: ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports. Retrieved from Education Resources Information Center website: http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED305016.pdf

[1] In this paper peer review, peer feedback, peer tutoring, and peer teaching are used synonymously. Although I recognize the political implications of each term and the time period or group that tends to use each term, I use them synonymously because of the practical similarities I want to highlight.

[2] The “flipped classroom” is a term used by educational technologists to refer to an approach whereby the traditional PPP approach (teacher Presents, students Practice, students Produce as the teacher assesses) is reversed: the teacher gets students to produce (take a quiz or problem solve first), to help each other (practice), and then, students to present to each other. The initial lesson (teacher presentation) is replaced by asking students to do homework such as watching a youtube video lecture the night before classroom time.