Mariana Maués Barreto, Federal University of Pará, Brazil

Barreto, M. M. (2019). Peer-led activities at a self-access center in Brazil. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 10(2), 41-56. https://doi.org/10.37237/100202

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

A Self-Access Center (SAC) is intended to foster autonomy in the process of learning an additional language. Activities facilitated by students are an excellent alternative for students as they increase their teaching skills and confidence as speakers of their additional language. This qualitative study reports on the experience of two learners who led activities at the Autonomous Learning Support Base (ALSB), a SAC located at the Federal University of Pará in the Brazilian Amazon. The survey application, as well as the interviews conducted with both facilitators, encouraged them to reflect on their roles as SAC facilitators and helped them to overcome inner difficulties and insecurities.

Keywords: Self-Access Center, activities by students, autonomous learning support

In this paper, I focus on activities facilitated by students at a self-access center in Brazil. From previous studies at the Autonomous Learning Support Base (ALSB) I found that facilitators were facing challenges such as lack of self-confidence and time management difficulties (Barreto & Magno e Silva, 2017). An array of strategies can be used to improve a SAC in order to make it an attractive learning and social space. In this sense, students who voluntarily conduct activities are an essential resource to a center even if administrators hesitate to use them as teachers, as there may be no guarantee that this system will work effectively all the time. The use of peers as activity leaders stimulates the creation of a new scenario in which difficulties such as lack of financial recourses or staff restrictions may be solved.

Through this research, sought to assist student facilitators in meeting participants’ needs and reflecting on their roles. of the background where the study took place, it then outlines the methodology, followed by the results and discussion.

Background

The ALSB is a Brazilian self-access center located at the Federal University of Pará. It has been operating since 2004 and “started as a supporting center for students with difficulties in their learning process” (Magno e Silva, 2017, p. 190). Nowadays the center ffers an array of learning materials, computers, activities (e.g., study groups, lectures, presentations, workshops, and conversation groups), access to other learners and authentic language users, as well as an advising program to assist learners with their language abilities, learning methods, and study plans. Thetaffrovide information to users, arrange the layout of the space, assist with activities, and are responsible for making some decisions along with the coordinator of the SAC about different initiatives to encourage students to use the facility.

As Gardner and Miller (1999) state, the surrounding culture influences learners’ beliefs and attitudes and SACs must be sensitive to these specific traits. Magno e Silva (2017) affirms that the ASLB users’ preferences and behaviorseflect the gregarious Brazilian culture. This means that Brazilians seem to prefer to learn by sharing ideas and solving problems in groups. Hence, the most attended events at the center have been the ones that promote social interaction and interdependence (e.g., workshop type activities), which can be proposed by members of the community, teachers or students.“The coordination [of the ALSB] believes that nobody knows better what students like and need than students themselves” (Magno e Silva, 2017, p. 201). Therefore, students often propose a variety of interesting and popular activities such as “Mobile Learning” (language learning through the use of cell phone apps), “Pacataca” (learning English by being part of a theater group), and “Faux Lettering” (learning Spanish through artistic calligraphy). By allowing learners to conduct activities such as the aforementioned ones, the ALSB promotes facilitators’ creativity, supports their trajectory towards autonomy, progressively breaks cultural paradigms of passive learning, and provides a more informal learning atmosphere outside the classroom. Activities held by students at the SACWhen facilitating an activity at the SAC, students are suported by a professor. Any student wishing to be a facilitator must complete an application form indicating the activity title, the responsible professor, location, time, target audience, a summary of the activity’s objectives, the target language, and the number of sessions, which may vary from a single day to an entire semester. This application is submitted to the SAC’s administration and during the weekly staff meetings, the activity proposal is analyzed and one of the staff members is appointed to give support for it. The support given by the staff includes booking the space where the activity will take place, promoting the event on social media and notice boards, providing a sign-up list, giving technical assistance during the activity and, finally, profiding certificates to the activity leaders and participants who attended at least 75% of the activity sessions (e.g., if the activity has seven sessions, the participants must attend a minimum of five sessions).

Theoretical Framework

Group activities

Group activities have been largely implemented in additional language acquisition over the past years. This approach is based on Vygotsky’s social development theory (1991), for which humans are social beings who learn by interacting with other individuals. Following this concept, Boud, Cohen, and Sampson (2001, p. 153) propose that groups are “a convenient way to provide information and education to several people at the same time”. Through groups, students are able to share ideas, solve problems and complete tasks. By being part of these “laboratories of social interaction”, learners may imitate each others’ behavior, observe reactions from their peers and realize that they are not the only ones facing challenges.

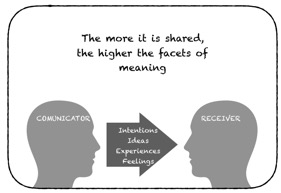

Disadvantages may also be experienced within a group activity. Signs of malfunction are observed when participants are bored, frustrated, non-committed, and demotivated. Boud, et al. (2001) highlight that every group is made of a number of variables that “may vary from healthy to unhealthy, growth enhancing to growth inhibiting” (2001, p. 157). The following figure illustrates the variables that surround the relationship established amongst members of a group:

Figure 1. Successful Communications (Inspired by Boud, Cohen, and Sampson (2001, p. 159)

Figure 1 illustrates that the success of a group may be measured by the members’ ability to transmit and receive ideas, experiences and feelings. As stated by Boud et al. (2001), the level of comprehension among the group members may be superficial or relevant. When the shared information is not meaningful, it may lead to a miscommunication between communicators and receivers.

Group activities from a complexity perspective

In 1997, Diane Larsen-Freeman published her seminal text on language learning and complex adaptive systems. Since then, much has been discussed on the subject. Larsen-Freeman and Cameron (2008) state that the most significant change offered by complexity theory is that the world is not composed by stable objectified entities but rather by constant change and adaptation. In this sense, Magno e Silva (2017) suggests that one of the basic principles of SACs in current times is to constantly adapt to users’ different profiles, providing a structure for activities and diversified learning opportunities.

The language used by a community can be described as a dynamic system, which is also true of interactions amongst learners and teachers, or amongst members of a same group. “Reconceptualizing these and other phenomena in terms of complexity opens up the possibility for new understandings and actions” (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008, p. 5). As a consequence, instead of analyzing group activities through the ‘cause-effect’ lense, one must consider its dynamic relationship amongst its multidimensional elements.

Even though the concept of group activities in figure 1 is clear and understandable, it fails to express its dynamicity, since it presents a pattern of static, dualistic thinking, and predictable consequences. Hence, it does not allow the system to be variable and to follow different trajectories.

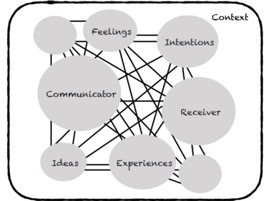

Based on past experiences, one might expect certain predictable results, but predictions cannot be precise because “nonlinear systems are sensitive and can change unexpectedly” (Larsen-Freeman, 2017, p. 17). Bearing this concept in mind, I suggest an illustration for successful communications among members of a group:

Figure 2. Successful Communications from a Complexity Perspective

Figure 2 is a simulation to elucidate the nonlinear association amongst members in a group. Some of the aspects that may influence this relationship are represented in the circles, but since it is virtually impossible to predict every conceivable aspect, the blank circles within the context comprise new potential aspects.

Somehow, amongst all the chaotic and unpredictable interactions, a complex order emerges. “This order‚ which is dynamic rather than static‚ provides affordances for active participants in the setting‚ and learning emerges as part of affordances being picked up and exploited for further action” (Van Lier, 2004, p. 8). In addition, it is important to highlight that as a consequence of the nonlinear relationship, the receiver does not develop the same model of language transmitted by the communicator. The communication process is affected by different external aspects and the message transmitted inside the group is a construction of each person’s particularities as a self-reflective intentional agent.

The use of peers in self-access centers

When addressing the role of peers in college and university campuses, Materniak (1984) affirms that students have been assisting each other since the colonial period of American history. Manning (2014), observes that students usually discuss classes and help each other with homework. In this sense, “every university already has an informal peer-support system” (Manning, 2014, p. 53). In addition, Newton, Ender, and Gardener (2013) highlight recent changes in the use of peers over the last few years. The most important of them is the proliferation in the use of students into a variety of academic and student services. In this sense, SACs are a great example of contexts where learners may be free to play new roles in language learning.

According to Boud et al. (2001, p. 3), “students learn a great deal by explaining their ideas to others and by participating in activities in which they can learn from their peers”. The benefits attributed to facilitators include an increase in self-confidence, the development of new teaching strategies, the improvement of skills on planning activities and in collaborative learning, as well as in providing and receiving feedback.

Regarding the benefits attributed to participants, they tend to experience considerably lower levels of anxiety from making mistakes, learn by observing their peers, and feel at ease to express themselves unreservedly. However, Boud et al. (2001) highlight that the informal use of peers may also result in confusing students who might be unaware of the role they are expected to play. To address these issues, the authors state that the activity guidelines must be clear and their purpose must relate to students’ needs. In addition, Manning (2014, p. 53) suggests that “to promote a positive experience for everyone, it is important for peer supporters to have access to help when faced with difficult questions or situations”. For all these reasons, it is important to discuss how centers can adapt to individual characteristics of facilitators and participants. This study describes how two data collection instruments, a survey and follow-up interviews after SAC workshops, served as reflection tools for the two SAC student facilitators. These exchanges of knowledge and experiences are powerful reflective teaching tools that enabled student facilitators to self-analyze various dimensions of their informal teaching events.

Methodology

The purpose of this research was to assist students who facilitated activities at the ASLB in meeting participants’ needs and reflecting on their roles as faciliators. The first step towards accomplishing this goal was to analyze and assist he two eer-led activities that took place at the SAC during the data collection month. As each activity happened once a week, I attended four sessions of each of the student-facilitators. This period allowed me to become familiar with the facilitators and the workshop participants. This period also gave both facilitators and participants enough time to interact with one another. After becoming familiar with the facilitators, I administered a parallel survey after each activity session. I also conducted interviews with both facilitators, who voluntarily agreed to be part of this study. Note that the names reported in this paper are pseudonyms. The first activity was “Watch n’ Learn” and was led by Dave, an undergraduate student of English who is in his early twenties. According to Dave, the activity intended to encourage learners of intermediate or advanced English proficiency level to learn new vocabulary by watching a TV series. He showed one TV series throughout the sessions. While watching the TV series, participants were expected to take notes on new vocabulary they heard. By the end of each episode, they were expected to share the new words they heard and infer the meaning together. By the end of the session, the facilitator would lead a discussion on the main theme or themes presented in the TV series episode.The second activity was named “Super Deutsch” and was led by Marco, an undergraduate student of German who is in his late twenties. According to Marco, the activity aimed to help learners of German as a foreign language to overcome their grammatical and pronunciation difficulties. He intended to achieve his goal by giving conventional expository lectures.Both activities had a total of seven enrolled participants from different backgrounds, gender and age groups. They were all asked to be part of the research and voluntarily agreed to participate. In order to triangulate information from both facilitators and participants about their expectations and challenges regarding the activity, I administered a parallel survey after each session. The survey was designed according to the guidelines proposed by Manning (2014, p. 55). Therefore, the use of corresponding questions allowed a parallel between the information gathered from participants and the information gathered from facilitators. Two surveys were designed and administered: one survey sought to gather suggestions from the students who attended the sessions (Appendix A). The other survey sought to help facilitators reflect and assess their own performance as facilitators (Appendix B). Both surveys included open-ended questions which helped to identify successful moments throughout the sessions, as well as the most challenging activities for participants. The participants’ answers were made available to the facilitators as an attempt to help them reflect on their performance. Finally, I conducted one interview with each of the two facilitators to check the validity of data collected in the parallel survey. These semi-structured, open-ended interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes. Even though I used the same interview guidelines, the conversation was kept flexible in order to allow participants to express themselves naturally. Both interviews were recorded and transcribed with the permission of the facilitators.

Results and Discussion

This section seeks to triangulate all data sources in an effort to assist students who facilitated activities at the ASLB in meeting participants’ needs and reflect on their roles as facilitators. First, I will present the results from Watch n’ Learn. Secondly, I will introduce the answers derived from Super Deutsch. Lastly, I will present results from interviews conducted with both facilitators.

Watch n’ Learn

The answers to the survey show a discrepancy between participants’ and facilitator’s opinions regarding some aspects of the activity. When answering the question “How do you evaluate the facilitator’s performance?”, the majority of participants profiled the facilitator as very supportive, approachable and capable of responding to all their questions. However, the answers given by the facilitator to the question “How do you evaluate your performance as a facilitator?” He felt that he was not, in fact, able to address all questions. As stated by Larsen-Freeman (1997, p. 143), “in complex systems, each component or agent finds itself in an environment produced by its interactions with the other agents in the system”. This fact is perceptible on figure 2; the non-linear communication depends on each person’s particularities and is affected by different aspects.

Participants also indicated their motivation and excitement to participate in the following activity sessions. Manning (2014) suggests that providing students with a meaningful role to fill may be a motivational stimulant. When first enrolled in the activity, participants were presented with a survey so they could express their suggestions and opinions. After becoming invested in the activity, participants felt motivated not only to attend the following sessions but also to see if their suggestions and opinions would be addressed.

Participants were asked to report on what could be improved and to give suggestions for the following sessions. The majority of participants recommended the selection of TV series with shorter episodes. hey also indicated that the activity after each episode had been repetitive and therefore not interesting. Hence, they proposed the use of different activities and exercises specifically related to the TV series theme. The facilitator also stated that he was not able to achieve every planned goal and had difficulties with time management. This imbalance can be related to the fact that he was playing the role of a student-facilitator. Consequently he was in the non-linear proccess of learning how to teach and how to deal with uncertanties. As stated by Larsen-Freeman (1997, p. 151) “the learning curve (…) is filled with peaks and valleys, progress and backsliding”.

After becoming aware of participants’ suggestions and commendations, the facilitator addressed the issues and improved the activities and attempted to better manage the sessions time by choosing shorter episodes. Therefore, at the end of each episode, he was able to dedicate more time to activities and discussions about the TV series. The facilitator also embraced the idea of continuously using a single TV series. This type of interaction was named by Larsen-Freeman and Cameron (2008) as co-adaptation, which consists of the “change in connected systems, where change in one system or component of a system produces change in the other” (Larsen-Freeman, 2016, p. 385). Thus, the example given demonstrates how interaction among facilitator and learners led to the emergence of one of the many possible patterns inside the system.

Super Deutsch

The answers to the survey show a correspondence between students’ and facilitator’s opinions regarding mostly aspects of the activity, which demonstrates the facilitator’s great teaching experience and high level of self-confidence. When assessing the facilitator’s capacity of addressing questions, all participants commended the student-facilitator for his excellent teaching skills and ability to answer questions. At the same time, the facilitator’s answers demonstrates his self-confidence and awareness of his own abilities. According to Materniak (1984), the peer leader must be knowledgeable about the language matter, as well as being able to explain specific subjects. The previously mentioned skills are valuable in an experienced student. However, by considering the dynamic quality of workshops as complex systems, we can state that facilitators are simultaneously interacting with a number of elements. Hence, they may improve their abilities, as well as suffer positive or negative influences as a result of the interaction with other components of the system.

When assessing his own performance, the facilitator stated that he felt satisfied with the activity course and throughout the sessions he was able to notice the increase in participants’ interest. Nonetheless, thecognizes that other aspects can still be improved. When assessing the facilitator, participants stated that Marco possesses excellent teaching skills and was fully attentive and approachable during the sessions. Using students as facilitators may be successful because both parties, students leading activities and students participating in those activities, share similar social roles and a similar knowledge base, which allows the facilitator to use familiar vocabulary and to explain concepts at an appropriate level. it is important to highlight that the non-linearity in complex systems suggests that the effect is disproportionate to the cause. For instance, attending a lecture of an important specialist can impact someone’s academic life, but sometimes it simply does not generate such results for a number of reasons: it may feel rather impersonal, or the explanations provided may seem overly intricate. Regardless the case, a casual meeting with colleagues at a self-access center may in fact be able to impact one’s learning learning curve.

Interviews

I interviewed both facilitators in order to further discuss the answers from the survey and to get gain an in-depth insight into their experience. Dave, the facilitator of “Whatch’n Learn” had previous experience as a teacher. He has been working in private language schools for three years. However, when asked about the difference between his previous practices and the experience as a facilitator at a SAC, he stated: “In the places where I worked before, I had to be attached to a specific methodology … but here at the ASLB I have more freedom”.

Magno e Silva (2017) states that the coordination of the ALSB has a dynamic perception and bases its administration on the theoretical view of language learning as a complex system. Thus, what the facilitator perceives as freedom is one of the main characteristics of dynamic systems; they are “continuously changing and adapting, sometimes shifting dramatically from one mode of behaviour to another, sometimes hovering flexibly “on the edge of chaos” (Cameron & Larsen-Freeman, 2007, p. 12).

Larsen-Freeman (1997) states that in dynamic, complex systems the effects are disproportionate to the cause. As an example, we can see that Dave’s initial expectations were very different from what actually happened during the sessions:

“When I started the project I had in mind that they [the workshop participants] would watch the same TV series throughout the sessions, but it was totally different from what I thought because they wanted to watch particular TV series per week… imagined that, for example, we would talk about our expectations for the following episodes and it would be an informal conversation, you know? But we were constantly watching the pilots from different TV series [Daredevil, Friends, and Everybody Hates Chris] and we did not discuss, we just shared the vocabulary we learnt from each episode… and they had a lot of new words, so we had no time for any discussion”.

The uncertainty faced by the facilitator is part of the complexity of the educational system “in which a multitude of forces interact in complex, self-organizing ways, and create changes and patterns that are part predictable, part unpredictable” (Van Lier, 1996, p. 148). Expert teachers tend to face these unpredictable events more easily, due to their vast background, while novice teachers usually struggle with unplanned situations. Consequently, due to the lack of experience, Dave had difficulties when he faced unforeseen situations. Davethe survey as an opportunity to get to know the participants’ needs, as expressed in his following comment:

“It was nice because I could understand what they expected from the activity… because even though I proposed the activity, it is not only mine, it is also theirs… so I want to know what they want to do”.

The fact that Dave ants to consider and take into account the participants’ opinions supports the complexity systems position that input is not enough for students to learn. As stated by Cameron and Larsen-Freeman (2007, p. 13), they need to “experience the second language as a dynamic system, shaping their complex dynamic systems of the new language through working with it, soft-assembling what they can from their resources for different tasks and purposes”.

The facilitator Super Deutsch, Marco, also had previous experience as a teacher. He has been working in private language schools for two years. When asked about his perception of his own skills and how he dealt with time management, Marco stated:

“With no modesty? I know that I can teach well … I only wish I had more time, but I didn’t… but I always finished what I planned… When I could not finish everything I had planned for that day, I continued on the next session”.

As Newton and Ender (2010) point out, there are limitations on what can be expected from peer-teachers. Some may have previous experience and be more self-confident, while others may need some form of assistance, as we saw in Dave’s answers. Marco exhibits another sign of self-awareness when asked about time management as the quote above shows. The activity is a complex system composed by elements such as students, emotions, experiences and intentions. These elements interact in multiple directions (see Figure 2) and over time these patterns change. As a consequence, the system self-organizes and adapts in response to these modifications. As an example, even though the facilitator considered the time allocated for the activity to be short, he was able to readjust to the unpredictable change.

Essentially, it appears that implementing a parallel survey influences mutual expectations. The sharing of participants’ comments encourages the facilitator to continue to improve and strive. This premise seems to be confirmed on Dave’s report “this way we can have some idea of what participants want… so we can adapt the activities or even propose other activities” and on the report of a participant of Watch n’ Learn: “It is nice because I keep thinking if he will accept my suggestions”.

Manning (2014) emphasizes that a SAC must adapt to students’ responses, motivating learners to interact and collaborate with each other. In addition, Magno e Silva (2017) highlights that “the strength of the systemic perspective is that it recognizes all agents, groups and institutions directly or indirectly involved in facilitating and engendering autonomy” (p. 185). Hence, through the administration of a parallel survey, the SAC adapted to changes and requests while it also effected participants’ engagement.

Implications and Further Research

The lack of experience perceived by the facilitators who participated in this study appears as a predictable scenario, and it can be remedied by indicating to them what particular areas need attention or improvement. The survey fulfilled its initial purpose of aiding facilitators to improve the quality of sessions by considering the feedback from participants and consequently reflecting on their roles inside the SAC.

Based on the research at hand, it is my understanding that there is a need for further research on the emotional dimensions and the inner struggles and challenges that facilitators may deal while leading an activity inside a SAC. Issues such as facilitators’ level of motivation, self-confidence, expectations for the activities, and level of anxiety in making mistakes would be pertinent areas of study and would contribute to greater peer-led activities inside SACs.

Conclusion

This research aimed to assist students who facilitate activities at the ASLB in meeting participants’ needs and encourage them to reflect on their performance as facilitators. To understand SACs as complex environments, based on Larsen-Freeman (2016) statements, it is vital to consider that the components of the system are not only the agents, that is, the facilitator and the participants, but also their accompanying thoughts, embodied actions, emotions, behaviors, dispositions, identities, as well as properties of the physical and temporal environment in which they are situated. Therefore, the analysis of the results revealed aspects related to time management, resourses, facilitator and participants’ interaction, teaching abilities, and self-confidence.

Students who take the initiative to propose and lead activities are an essential resource to any SAC. The results of this study reinforce the theory that a regular support to activities held by undergraduate students, gives them opportunities to overcome difficulties such as fear of the unpredictable and time management constraints. In addition, it helps undergraduate students acting as facilitators to expand their teaching skills and to increase their self-confidence.

Peer-teaching is used in a number of contexts, however, it is still in need of further research and development inside SACs. The centers tend to fossilize if they are not constantly improving and reinventing themselves to attract learners to engage in independent informal learning. Hence, the use of students in peer-teaching can be a way of disturbing the traditional system and cause the necessary turbulence to keep self-access centers in constant movement and evolution.

References

Barreto, M., & Magno e Silva, W. (2016). Atividades ministradas por alunos em centros de autoacesso.[Activities by students in self-access centers]. Belém: Programa Institucional de Bolsas de Iniciação Científica, 20.

Boud, D., Cohen, R., & Sampson, J. (2001). Peer learning in higher education. London, UK: Kogan Page.

Cameron, L., & Larsen-Freeman, D. (2007). Complex systems and applied linguistics. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 17(2), 226–240. doi:10.1111/j.1473-4192.2007.00148.x

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (1997). Chaos/complexity science and second language acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 18(2), 141-165. doi:10.1093/applin/18.2.141

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2016) Classroom-oriented research from a complex systems perspective. SSLLT, 6(3), 377-393. doi:10.14746/ssllt.2016.6.3.2

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2017) Complexity theory the lessons continue. In L. Ortega, & H. Zhaohong (Eds.), Complexity theory and language development: In celebration of Diane Larsen-Freeman (pp. 11-50). Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Larsen-freeman, D., & Cameron, L. (2008). Complex systems and applied linguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Magno e Silva, W. (2017) The role of self-access centers in foreign language learning autonomization. In: C. Nicolaides & W. Magno e Silva (Eds.), Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics and learner autonomy (pp. 183-207). Campinas, Brazil: Pontes Editores.

Manning, C. (2014) Considering peer support for self-access learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(1), 50-57. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/mar14/manning/

Materniak, G. (1984) Student paraprofessionals in the learning skills center. In S. Ender & R. Winston (Eds.), Students as paraprofessional staff (pp. 23-35). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Newton, F., Ender, S., & Gardner, J. (2013). Students helping students. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Van Lier, L. (1996). Interaction in the language curriculum: awareness, autonomy, and authenticity. London, UK: Longman.

Van Lier, L (2004). The ecology and semiotics of language learning: A Sociocultural perspective. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1991) A formação social da mente. São Paulo, Brazil: Martins Fontes.

Appendices

Appendix A

Participants’ Survey

FICHA DE AVALIAÇÃO DA ATIVIDADE

Hoje o(a) ministrante conseguiu responder as perguntas que nós (os participantes) fizemos.

SIM ( ) NÃO ( )

Hoje eu tentei responder as minhas próprias perguntas/dúvidas.

SIM ( ) NÃO ( )

Hoje eu fui participativo(a) na oficina.

SIM ( ) NÃO ( )

Hoje a oficina fluiu naturalmente e as atividades foram interessantes.

SIM ( ) NÃO ( )

Hoje eu me senti satisfeito(a) com a atividade da qual participei e estou motivado(a) a continuar.

SIM ( ) NÃO ( )

Como você avalia a atuação do ministrante da oficina hoje?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

O que você mais gostou na oficina hoje?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

O que você acha que poderia ter sido melhor?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Quais são as suas sugestões para a próxima sessão da oficina?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Appendix B

Facilitator’s Survey

FICHA DE AVALIAÇÃO DA ATIVIDADE

Hoje eu consegui responder as perguntas feitas pelos(as) participantes.

SIM ( ) NÃO ( )

Hoje eu ajudei os(as) participantes a responder suas próprias perguntas.

SIM ( ) NÃO ( )

Hoje eu consegui interagir com todos(as) os(as) participantes.

SIM ( ) NÃO ( )

Hoje eu consegui colocar em prática todas as atividades que planejei.

SIM ( ) NÃO ( )

Hoje os(as) participantes pareceram gostar das atividades que eu propus.

SIM ( ) NÃO ( )

Como você avalia a sua atuação como ministrante da oficina hoje?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Como você avalia a participação dos alunos na sua oficina hoje?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Na sua opinião, qual foi a melhor parte da oficina hoje?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Qual parte da oficina você melhoraria?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________