Tim Murphey, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Yoshifumi Fukada, Meisei University, Japan

Joseph Falout, Nihon University, Japan

Murphey, T., Fukada, Y., & Falout, J. (2016). Exapting students’ social networks as affinity spaces for teaching and learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(2), 152-167. https://doi.org/10.37237/070204

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

Students’ social networks can become exapted (Johnson, 2010) for the purpose of increasing language learning, or any other kind of learning, as well as the promotion of well-being, through what Murphey (2014) calls the well becoming through teaching (WBTT) hypothesis. The WBTT paradigm holds that people not only learn better when teaching others, but approach and maintain their well-being in wider social networks outside the classroom. The present study explored the impact of WBTT-based activities conducted within students’ social networks on their language learning and well-being. The data were collected for 6 years (2010-2015) from students’ action logging and case studies. Language students taking Murphey’s English classes were asked to self-report their experiences and to write reflections after their WBTT-based activities. The qualitative data indicated that both the students in the teaching role and the people who received their lessons deepened their understanding of both the content (message) and form (target language), forming affinity spaces in different social contexts both in and out of class. Most importantly, it was recognized that both groups of people were able to experience exciting learning or teaching rushes through the engagement in the activities.

Keywords: exaptation, social networks, affinity spaces, teaching-to-learn

Exaptation, a term coined by evolutionary biologists in an influential paper (Gould & Vrba, 1982), originally described when “an organism develops a trait optimized for a specific use, but then the trait gets hijacked for a completely different function” (Johnson, 2010, p. 153). For example, feathers on birds were originally used for heat regulation before being exapted for flight. The term exaptation itself branched out from its biological origin into other uses. An example of technological exaptation would be Gutenberg’s appropriation of the design of the wine press for his invention of the world’s first printing press (Johnson, 2010). In education it has recently been proposed that students’ social networks outside of class can become exapted for the purpose of increasing language learning, or any other kind of learning and the promotion of well-being, through the well becoming through teaching (WBTT) hypothesis (Murphey, 2014). While the positive impact of students’ peer tutoring on their learning has been pointed out in past studies (e.g., Damon, 1984; Fantuzzo, Riggo, Connelly, & Dimeff, 1989), the WBTT hypothesis holds that people not only learn better when teaching others, but approach and maintain their well-being in wider social networks outside the classroom (e.g., their friends, parents, or their acquaintances in the community). They also can increase both their social capital (the strength of their networks) and their self-awareness of possessing cultural capital (i.e., cultural knowledge of value).

Teachers may often be aware that they are gaining numerous cognitive and affective benefits by teaching, but their students might be surprised to hear this and conclude that if this were indeed the case, then the person who is learning the most in the classroom is the teacher. But what if the students themselves were invited to teach? What, where, and who would they teach? And maybe more intriguingly, would they gain the same benefits as their teachers? The present study attempts to begin answering these questions with an investigation involving the self-reports from language students who taught what they learned in class to those they choose to teach outside of class. The WBTT-based activities could be initiated not only in the classroom but also in other types of educational programs including self-access learning programs (e.g., Hughes, Krug, & Vye, 2012), tutoring programs (e.g., Mynard & Almarzouqui, 2006), and reciprocal teaching (Palincsar & Brown, 1984). That is, learners can teach what they have learned in any particular space to others in other spaces.

Any “place or set of places where people can affiliate with others based primarily on shared activities, interests, and goals, not shared race, class, culture, ethnicity, or gender” (Gee, 2004, p. 73) can become an affinity space. Affinity spaces comprise social locations where groups of people are drawn together because of a shared strong interest and engagement in a common activity. Affinity spaces can foster situated learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991), when skills or knowledge are transferred through mutually shared actions and goals. Gee (2004) states that “humans understand content, whether in a comic book or a physical text, much better when their understanding is embodied: that is, when they can relate that content to possible activities, decisions, talk, and dialogue,” (p. 39), and also that “when people learn as a cultural process, whether this be cooking, hunting, or how to play video games, they learn through action and talk with others, not by memorizing words outside their contexts of application” (p. 39). Thus when students go out of the class to teach in their individual social networks, their activities can enable situated learning. If what they are teaching relates meta-cognitively to the target language, or simply if the medium of exchange is through the language (and allowing for code-switching with their mother tongue), situated language learning is promoted among the students and who they are teaching.

The proponents of situated learning, Lave and Wenger (1991) and Gee (2004), state that this learning represents the acquisition of new identities through the engagement in social practices or interactions. For teaching-to-learn outside the classroom, students can acquire identities as valuable knowledge holders, positioning themselves in teaching roles. This identity reconstruction through social practice is expected to promote self-awareness of social capital (Bourdieu, 1986), that is, the capability of having positive impact on one’s own life and on others (Fukada, 2015). Classes can form affinity spaces that spill over into various other spaces beyond the classrooms, into hallways, cafeterias, sports fields, buses or trains, and neighborhoods, as well as in “newsletters and other sorts of texts, websites, computer bulletin boards, email chains, and conferences” (Gee, 2004, p. 87). This can be stimulated even more by giving the task of teaching to others out of class what student are learning in class. When this is given as a standard homework procedure, both students and teachers are more concerned with material that can travel, i.e., be valuable for not only for classroom study but in extended networks. Such practice can facilitate the validation of the teaching subject (and the language in which it gets taught) as cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1986), the benefit of non-material exchange, and also the students’ formation of their own affinity spaces in relation with others within their social networks.

With a little imagination, these social network spaces can also be exapted as extended classrooms with appropriately interesting classroom activities. While such learning and sharing happens naturally in affinity spaces, students find that they need to carefully consider who in their social networks would be interested in what and how they are teaching it—specifically, who might want to learn about English by using it. This is because each person in the students’ social networks has different socio-cultural and socio-historical backgrounds and different Discourses (i.e., different ways of acting, interacting, and also valuing) (Gee, 2004, 2011, capitalized by Gee). While some people in their social networks may perceive the learning material as valuable, others might see them just as chunks of information. That is, any knowledge or skill cannot exist statically as cultural capital, but can be perceived as capital in relation with others situated in the social space. In addition, when teachers give such assignments, they also need to look for material that is valuable to many others in students’ networks as well as to the students themselves (value-added language learning; Murphey, 2013). And when these are realized and teachers get regular teaching reports from students, they often notice that students seem to have a teaching rush, i.e., well becoming through teaching (Murphey 2016, examples further below).

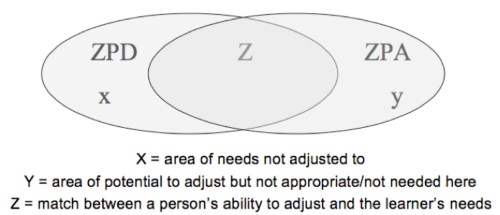

Exapting social networks as affinity learning spaces involves opening learner’s zones of proximal development (ZPDs; Vygotsky, 1978), the ranges of target-abilities that can be developed through receiving relevant-level information and guidance (in the right amounts) from more competent (student) peers, and at the same time engaging their zones of proximal adjusting (ZPAs; Murphey 1996; 2013), the ranges of capacity to adjust. Now let’s unpack the concepts of ZPD and ZPA a bit more. As two people jointly adjust to one another, they co-construct an affinity space. Shulman (2004) cites David Ausubel’s (1968) epigraph in his textbook Educational Psychology: A Cognitive View, “If I had to reduce all of educational psychology to just one principle, I would say this: The most important single factor influencing learning is what the learner already knows. Ascertain this and teach him accordingly” (Shulman, 2004, p. 36). This discovering of what students already know is the foundation of scaffolding procedures and the opening of someone’s ZPD. Opening learners’ ZPDs may be seen as a pre-requisite to design appropriate materials for the peer teaching activity. However, realizing this requires developing a wide ZPA in student-teachers. This is probably best learned in action while teaching, it is not something we can absorb from reading a textbook. Thus, we might as well get student-teachers started early by teaching each other daily, in and out of class. And chances are that they partially already know how to adjust to friends and family in their affinity spaces and that further teaching helps them develop more adjusting abilities (i.e., a broad ZPA, see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Zone of Learning Flow (from Murphey, 2013, p. 175)

Methods

The WBTT hypothesis was developed based on Murphey’s teaching experiences some years ago with mostly 3rd and 4th year university foreign language students at first, and then later with students in all four years. He found students, who were taking his English communication courses at a private Japanese university, seemed to learn so well by teaching each other in class that he gave them the everyday homework of teaching what they were learning in his classes to others outside of class. It made him think twice about the material he was using to teach them. He wanted the material to be interesting to others outside of his classes also. Then he asked the students to write short reports in English of their efforts in their action logs or notebooks (Murphey, 1993; Murphey, Barcelos, & Morales, 2014), both successes and failures, and he later started asking them to use spaced repetition with “their students” and to do follow-up quizzing. Then he asked them to write up case studies, which evolved into many student-centered class publications (Murphey, 2014; 2016) showing how students taught and learned through teaching and enjoyed interacting with others using the learning materials. Murphey repeatedly read and analyzed students’ case studies in the class publications without a preset coding frame, which allowed themes to naturally emerge: Most students reported that their teaching (1) helped them to learn the material better, (2) deepened and broadened their understanding of the material, (3) enhanced their relationships with their “students,” and (4) made them feel good because they were helping others learn valuable information, the WBTT (Murphey, 2016). There were only a few slightly negative experiences where a student tried to force too much information to fast upon his/her students. These were left in the publications as guides to things that could go wrong when “teachers” do not appropriately adjust to “learners’” ZPDs.

Activities given in classes for students to teach in their affinity spaces out of class, at least at first, need to be scaffolded within the learners’ ZPDs. They also need to be seen as valuable for others to learn or to be co-validated as cultural capital in the students’ social networks. These activities may be one-line songlets or popular kotowaza (proverbs), first in Japanese, Warau kado niwa fuku kitaru, then in English, Smiling brings you happiness, let it show the way; or the 8 ways to reduce stress in the acronym COPS BEES (Mayo Clinic, 2003, see Appendix); or the 10 idioms they learn in class with gestures; or the 7 ways of improvisation (Morris, 2012; see Appendix). From these different types of topics, students could choose freely one or more for teaching what they and their “students” felt were valuable and meaningful. Students in later semesters were also allowed to read what their peers in previous classes had done as possible guiding examples. Murphey also gave them quotes from previous students’ work to show them that the sharing actually worked and could be enjoyable.

As of January 2016, there are 17 booklets online of case studies of students teaching and interacting outside of classes (https://sites.google.com/site/folkmusictherapy/home). Sixteen booklets contain case studies by 3rd and 4th year students from Murphey’s content-based classes (usually around 26 students participated in each booklet) on (1) Music and Song (twelve booklets) and (2) Changing the World (four booklets). The other booklet, with about 50 shorter case studies, is from Murphey’s larger-sized class, Ways of Learning, a class that is open to students in all 4 years and all departments. Each class member got a copy of their class’s booklet, and extra copies were made to loop forward into other classes for further student reading, enjoyment, and modeling of previous students in a kind of self-referential feedback and feed-forward for students in general (Falout, Murphey, Fukuda, & Fukada, 2016).

Let us summarize the iterative levels of learning going on here: From teacher-fronted teaching, students are quickly scaffolded into helping each other in pairs answer content questions (or singing a song, or re-telling a story) repeatedly in class,at first. Secondly, they are asked to choose class-based material and to teach people out of class and report on these experiences in their action log notebooks after every class (which Murphey reads each week). Thirdly, near the end of the semester, students individually choose some of the material from the semester to teach to someone outside the class, and then write this experience in a case study that is to be published in a class publication. In sum, the first two levels of experiences are written about in their action logs for Murphey to follow and adjust to (ZPA). Then the students write a longer case study (not part of their action logs) for a class publication in the form of a booklet.

The case studies in the class publications are actually conducted very autonomously. The students choose from a lot of teacher-presented material, or they invite their “student” (who they also choose) to help select the material to learn (being student-centered), and they choose the times and places and how they will follow up with spaced repetition.

Results

The WBTT hypothesis describes the positive feelings teachers can have at seeing someone learn. Many students comment about it in their action logs and case studies. Below is one full case study from 2010 when Murphey began this research and started publishing his students’ work in class publications online.

Case Study 11. Minori Wakaume* (Music Therapy Case Studies #1, 2010, pp. 15-16)

I chose my father, Misao, to teach an affirmation song to. He is 57 years old. He is an employee at a town office and he always has to think about residents and his subordinates, so I think he gets tired easily. I wanted him to be relaxed. Therefore, I chose to teach an affirmation song to him. I chose “The five ways to happiness” because I thought it would be the most useful song for him. The five ways “smile from ear to ear, breathe in deep, look up at the sky, sing a melody, dare to show your love” are really practical. When we do the five ways, we can feel happy and be relaxed immediately. Moreover, the melody is also fantastic. The melody is very cheerful and catchy, so I thought it would be his fancy!

At first, I explained about affirmation songs and the lyrics of the song. He knows English a little, so he seemed to understand at once. Then, I taught him the melody, He said, “I love this song.” And he was enjoying singing it, so I was happy, too. I was surprised that he seemed to be a little silly while he was singing! Next day, I asked him “What’s the five ways to happiness?” and he remembered only three ways. It was complicated for him to remember five ways, so I suggested singing when he does his favorite thing (for example, when taking a bath). A few days later, I asked the same question. To my surprise, he could sing the song perfectly. He said, “I like the song, so sometimes I was singing while I was walking” (walking is his routine). And when he sings the song while walking, he walks longer than usual. He seemed to enjoy walking with singing.

After teaching the affirmation song to him, I found that he looks more relaxed and happier than before. He often hummed the song at home. He said, “I want to tell the song to my subordinates. They would have a liking for the song.” My mother also seemed to be happy when she saw my father’s smile. I was also happy because I could have a chance to talk and interact with my father. Thus, the song had a good effect for not only him, but also my family. If I have a chance, I want to tell my friends about affirmation songs, too.

The following quotes are from the 2013 and 2014 songlets data (italics and bold are Murphey’s emphasis), which can also be found on the above website, and which illustrate the teaching rushes, or the WBTT hypothesis [brackets give some details of the people being taught, space, and time]:

- [little brother, at home over 3 days] . . . watching someone’s skill improve was very exciting (Yonaha, 2013, p. 8).

- [mom, at home over 3 days] the most important thing is how much I could enjoy teaching! While I was teaching songs, I could enjoy it and my mother seemed to enjoy singing new songs. Our enjoyment made it a successful project! (Sekine, 2014, p. 17).

- [dorm rooms and school, 2 days] It is an effective way to teach that mixes study with happy things (Sato, 2013, p. 27).

- [co-worker, at part-time job over 2 days] We laughed many times. We almost forgot that this was studying (Omagari, 2013, p. 28).

- [home] It was really nice opportunity for me to communicate with my father. I thought sharing good songs makes us happy. I will keep teaching songs and things that I learned in this class to everyone (Yamamoto, 2014, p. 4).

While the above extracts show directly the changes in emotions that students in the teacher’s role had, many more show the exciting changes in the recipients as the knowledge and skills get passed along, implying a learning rush as well:

- [home & phone] After a week, I decided to call . . . she said suddenly, ‘I can change my own mind by singing a song a little bit. I try to change my mind positively more from now. Thank you for your teaching! Please teach me more . . . ’. In conclusion, when we sing a song that includes happiness and meaningfulness, people tend to create positive thinking as above . . . singing a song is a tool to give good effects for mental and physical health (Koge, 2012, p. 11).

- [home & with certain people] I manage my stress by singing this song [‘What do you love?’]. . . . The laughing part was too embarrassing to sing at class. However I didn’t feel embarrassed at home with my mother. Rather I enjoyed singing it with her. . . . That went beyond my imagination . . . I appreciate my mother (Enomoto, 2012, pp. 8-9).

- [work-part time job] from 6pm–midnight . . . I sang it and showed the gestures during a pause in our work. . . . Two hours later when we cleared the tables I started singing the song and she joined me. . . . We worked humming it for the rest of this work time and enjoyed it . . . our hard working time changed to an enjoyable working time. The song made us happy. She told me that she wanted to sing more English songs. . . . I really enjoyed doing this case study because now I have someone to sing with at my part-time job. Now, we are happier (Sato, 2013, p. 12).

- [friend, face to face & phone, invoking Disney space] He wanted to know another song, so I taught “how are you” . . . He loved it more than the first because he already knew the melody as a Disney song . . . I found this teaching interesting and difficult. I was interested in how he changed. I could see the changing of his singing and attitude. At first he was not interested in singing an English song, but after he could sing ‘Why do you smile?’ he wanted to learn another song. This changing was really an interesting point (Kobayashi, 2015, p. 10).

From a pilot study, Murphey (in progress) asked students in three of his classes” to comment anonymously on their teaching in and out of class. One student responded as in 10 below:

- [friends, phone, face to face, inviting more friends] Call report is for that day’s partner but I don’t think that way! I think it doesn’t have to be one-on-one. When I do the call report, most of the time I am with somebody. My partner and my friend can be friends (ex. Doing call report in SALC and talking together).

The above comments signify that both the students in the teaching role and people who received the out-of-class lesson deepened their understanding of both the contents (i.e., message) and form (i.e., target language) of the lessons through social practices. In other words, both knowledge and skills were embodied through their engagement (Gee, 2004; Lave & Wenger, 1991) across various out-of-class social spaces such as homes, dorm rooms, workplaces, and self-access learning centers (SALCs), as presented in the above cases.

Discussion

The WBTT hypothesis posits that if students teach others what they are learning, they can learn more together than by studying alone, with the additional benefits of added or sustained interest, happiness, meaningfulness, and resilience in learning something challenging—or in other words, experiences of well becoming. By the students’ own accounts (above), they are able to help themselves and others learn something while simultaneously experiencing moments of well becoming. They mentioned aspects such as: forgetting that the activity was actually something they would otherwise normally identify as studying; enjoying the activity itself; experiencing elevations in their levels of engagement; experiencing decreases in debilitative language learning anxiety; imparting knowledge, skills, and joy (i.e., cultural capital) to others via situated learning—in other words, experiencing teaching rushes.

Recently in language learning it has become recognized that learning is not tied to an immovable, static, and well-defined space and place, such as within four walls of a classroom (Falout & Stewart, 2014; Murray & Fujishima, 2016). Likewise, the fluidity of space in learning became underlined in this study. Students reported taking the activities from their English classes to home, teaching family members, and to work, teaching colleagues. These interactions brought about increased interest and sustained learning in the content (i.e., message) and form (i.e., target language) of the learning. Such shared engagement in mutual interests and goals suggests the formation of affinity spaces outside of class, which in turn suggests the portability of affinity spaces. Since shared engagement of people is what constructs affinity spaces, then affinity spaces can be just as portable as the people and their interests and identities can be mobile.

The fluidity or portability of affinity spaces has a relationship with the identities of the individuals involved, their interpersonal relationships, and their ZPAs and ZPDs. Case Study 11 offers examples of these. Minori realizes her father knows English, and by agreeing to take an English lesson from her, the father validates not only English activities but also Minori’s cultural capital. As her father struggles to learn the song she teaches him, Minori works within his ZPD and uses her ZPA to adjust, and suggests that her father practice the song while doing other favorite activities. The father practices the song while having baths, moving about the house, and taking walks. Thus his singing and humming becomes embodied alongside daily routines, and even changes his behavior and emotions, putting a smile on his face, and extending the length of his walks and increasing the enjoyment of them. The father’s mobility increases the spaces in which he practices his daughter’s lessons, and with their shared interest and engagement, daughter and father turn their home into an affinity space where songs are sung. The portability of affinity spaces can also be implied as the father considers taking this song and teaching it to his subordinates at his place of employment. The most important outcome for Minori, however, was the happiness that spread among the family through emotional contagion, the social attraction of emotions (Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 1994), which provides supporting evidence for the WBTT hypothesis.

While we can learn a lot from reading others’ experiences, such as Minori’s, it is more convincing when we actually experience something ourselves (Dewey, 1910; 1963) or engage ourselves in the social practices or interactions (Lave & Wenger, 1991) that can lead to teaching rushes. (Teachers reading this article can better understand its main points when they actually experience for themselves how these concepts help learners learn through teaching.) Comments 6 and 10 reveal one way to encourage students to teach each other outside of class: calling each other on their phones. This is another standard, everyday homework in Murphey’s classes; to call that day’s partner and review what they learned in class. The student in Comment 10 is apparently very social and likes to include other people as well, expanding the situated practice across the social network, and sometimes doing the review face to face rather than on the phone. So the spaces and places for learning can be determined mostly by students themselves, and the activities they generate in these networks and spaces are also directed by them. Comments 6 and 10 also reveal that the students recognize the power of cultural and social capital in relation to their language learning and even health. Assigning students to teach outside of the classroom or SALC is one way to jump-start the exaptation of their social networks as learning spaces. If the students take up an interest in these practices beyond the purposes of doing the homework, then they have taken up the interest as their own, something that becomes identified between themselves and others, and then the learning spaces within social networks become exapted as affinity spaces.

Perhaps the next step in the WBTT approach is to consider further ways in which the spaces can travel, with or without assigning homework. We know a classroom is interactively stimulating, and the lessons have become embodied, when students start comparing it to places outside of class where they have had good experiences practicing, learning, and engaging with others in something they mutually value. Perhaps that is the test of a great space or activity; can it travel? Do students enjoy learning so much in class, or within school-instituted programs, including self-access learning programs, that they can carry their cultural capital and positive feelings into other places, sharing interests and activities with others, and making these places affinity spaces?

Conclusion

For exaptation of social networks as out-of-class affinity spaces, congeniality is crucial. People usually need to like each other and trust each other and be unafraid of making mistakes in front of each other before they can learn from one another. Participants need to be accepted for who they are, and how they identify themselves, and new participants need to be welcomed. Gee (2004) proposes eleven features for affinity spaces, some of which promote situated connecting and socializing as well as welcoming, accepting, and respecting others, both socially and psychologically. We mention only three here: (1) “common endeavor, not race, class, gender, or disability, is primary” (p. 85); (2) individuals are encouraged to utilize distributed knowledge “in such a way that their partial knowledge and skills become part of a bigger and smarter network of people, information, and mediating devices” (p. 86) (cf. expansive learning); (3) “Leaders are porous” (cf. ZPA) and they (including students in the role of teaching in this case) do not “order people around or create rigid, unchanging, and impregnable hierarchies” (p. 87). Thus, students’ social networks can be exapted as language learning or teaching affinity spaces, and furthermore, the affinity spaces can be exapted for the environmental strengthening of students’ social capital and agency, and also for the self-awareness of their empowerment, i.e., increased competence, agency, and autonomy. All of these affordances come together in the teaching-to-learn paradigm and the well becoming through teaching hypothesis.

Notes on the Contributors

Tim Murphey (PhD, Université de Neuchâtel, Switzerland) is a professor at Kanda University of International Studies. He is the editor of TESOL’s Professional Development in Language Education series and researches evolutionary Vygoskian sociocultural theory, positive psychology in education and music in multi-disciplinary ways.

Yoshifumi Fukada is a professor in the Department of International Studies at Meisei University, Tokyo. His research interests include L2 learners’ and users’ dynamic identities, their agency in their Englishlearning and social interactions (in and out of class) and L2 learners’ situated target-language learning in their affinity spaces.

Joseph Falout, an associate professor at Nihon University, has authored or co-authored over 40 papers and book chapters about affect, motivation, and group dynamics. His collaborations include creating ideal classmates, present communities of imagining, and critical participatory looping. He is an editor for JALT’s OnCUE Journal and the Asian EFL Journal.

References

Ausubel, D. (1968). Educational psychology: A cognitive view. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. E. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory of research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-258). New York, NY: Greenword Press.

Damon, W. (1984). Peer education: The untapped potential. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 5(4), 331-343. doi:10.1016/0193-3973(84)90006-6

Dewey, J. (1910). How we think. Boston, MA: D. C. Heath.

Dewey, J. (1963). Experience and education. New York, NY: Collier.

Falout, J., Murphey, T., Fukuda, T., & Fukada, Y. (2016). Whole-class self-referential feedback from university EFL contexts to the world: Extending the social life of information by looping it forward. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25(1), 1-10. doi:10.1007/s40299-015-0227-4

Falout, J., & Stewart, A. (2014). Space, place and autonomy in language learning: Joe Falout and Alison Stewart discuss the symposium at AILA 2014. Learning Learning, 21(2), 24-30.

Fantuzzo, J. W., Riggio, R. E., Connelly, S., & Dimeff, L. A. (1989). Effects of reciprocal peer tutoring on academic achievement and psychological adjustment: A component analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology. 81(2), 173-177. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.81.2.173

Fukada, Y. (2015). Trans-bordering cultural capital: A case study of one Japanese international student’s acquisition of TL-mediated socializing opportunities. JACET Journal, 59, 169-186.

Gee, J. P. (2004). Situated language and learning: A critique of traditional schooling. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (2011). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gould, S. J., & Vrba, E. S. (1982). Exaptation: A missing term in the science of form. Paleobiology, 8(1), 4-15. doi:10.1017/s0094837300004310

Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J., & Rapson, R. (1994). Emotional contagion. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Hughes, L. S., Krug, N. P., & Vye, S. L. (2012). Advising practices: A survey of self-access learner motivations and preferences. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(2), 163-181.Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun12/hughes_krug_vye/

Johnson, S. (2010). Where good ideas come from: The natural history of innovation. New York, NY: Penguin.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Mayo Foundation (2003). 8 ways to help reduce stress. Retrieved from http://life.gaiam.com/article/8-proven-ways-manage-stress-tips-mayo-clinic

Morris, D. (2012). The way of improvisation. Uploaded by TEDx Talks on Jan 7, 2012.

Murphey, T. (1993). Why don’t teachers learn what learners learn? Taking the guesswork out with action logging. English Teaching Forum, 31(1), 6-10.

Murphey, T. (1996). Proactive adjusting to the zone of proximal development: Learner and teacher strategies. Paper presented at the 2nd Conference for Socio-Cultural Research Vygotsky and Piaget; Geneva, Switzerland: September 1996, Psychological Sciences Research Institute: Geneva, Switzerland.

Murphey, T. (2013). Adapting ways for meaningful action: ZPDs and ZPAs. In J. Arnold & T. Murphey (Eds.), Meaningful action: Earl Stevick’s influence on language teaching (pp. 172-189). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Murphey, T. (2014). Singing well-becoming: Student musical therapy case studies. In Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 205-235 doi:10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.4

Murphey, T. (2016). Teaching to learn and well-become: Many mini-renaissances. In T. Gregerson, P. McIntyre, & S. Mercer (Eds.), Positive psychology in SLA (pp. 324-343). Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK.

Murphey, T. (in progress). Asking students to teach: Creating a looping task-based expansive learning community for teachers and learners. Innovations in Language Teacher Education.

Murphey, T., Barcelos, A., & de Moraes, R. (2014). Narrativizing our learning lives through action logs and newsletters. Revista Contexturas, 23, 99-111.

Murray, G., & Fujishima, N. (Eds.) (2016). Social spaces for language learning: Stories from the L-café. Basingstroke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mynard,. J., & Almarzouqi, I. (2006). Investigating peer tutoring. ELT Journal, 60(1), 13-22. doi:10.1093/elt/cci077

Palincsar, A. & Brown, A. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehension fostering and monitoring activities. Cognition and Instruction, 1(2), 117-175. doi:10.1207/s1532690xci0102_1

Shulman, L. (2004). Teaching as community property. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Students’ Song Booklet Citations (Class Publications https://sites.google.com/site/folkmusictherapy/home)

Ito, M. (2013) The joy of laughing and singing. In T. Murphey (Ed.), Music Therapy Case Studies, 4, 13.

Kobayashi, F. (2014). In T. Murphey (Ed.) Music Therapy Case Studies, 7, 10.

Koge, Y. (2012). In T. Murphey (Ed.) Music Therapy Case Studies, 3, 11.

Omagari, Y. (2013). Five ways friend. In T. Murphey (Ed.) Music Therapy Case Studies, 5, 28.

Sato, A. (2013). Singing while we work. In T. Murphey (Ed.) Music Therapy Case Studies, 4, 12.

Sato, T. (2013). How do you write? In T. Murphey (Ed.) Music Therapy Case Studies, 5, 27.

Sekine, M. (2014). Teaching songs project. In T. Murphey (Ed.) Music Therapy Case Studies, 6, 17.

Yamamoto, A. (2014). In T. Murphey (Ed.) Music Therapy Case Studies, 8, 4

Yonaha, M. (2013). Doi Ta Ga. In. In T. Murphey (Ed.) Music Therapy Case Studies, 4, 8.

Wakaume, M. (2010). Music Therapy Case Studies 1, 15-16.

17 booklets are available at https://sites.google.com/site/folkmusictherapy/home

(12 from the Song and Music class, 4 from the Change the World class, 1 from the Ways of Learning class)

Appendix: Optional Materials Taught by Students

Eight Ways to Reduce Stress

Teacher-made handout originally from a Minute Made orange juice container, but information attributed to http://www.MayoClinic.com

Class-facilitated with the acronym COPS BEES for easier memorization:

Connect Stay connected to family and friends.

Organize Organize yourself so that you know where things are.

Positive Talk to yourself positively. Spend time with positive people.

Simplify Prioritize and pace yourself.

Breaks Take time to relax, stretch, or take a walk during the day.

Eat well When you eat well and you’re healthy you are better able to handle stress.

Exercise well Some people find exercise not only healthy, but a good outlet for stress.

Sleep well Make time to sleep enough. Take power naps if they help.

Seven Ways of Improvisation (facilitated by the acronym PLLYARF, and the Tedx talk by Dave Morris): Play, Let yourself fail, Listen, say Yes, say And, follow the Rules (play the game), relax and have Fun

Five Ways to Happiness! English Song: (Tim Murphey) (facilitated with gestures and the well known Christmas tune ‘12 Days of Christmas’)

When you want to be happy, there’s (#) thing(s) you can do…

(#: one, two, three, four, five) (Tune: ‘12 Days of Christmas’)

- Smile from ear to ear.

- Breathe in deep.

- Look up at the sky.

- Sing a melody.

- Dare to show your love.

Students also had about 20 other short songs (songlets) like the one above to choose from for their teaching.

Ten Idioms (facilitated with gestures)

- my lips are sealed

- sweet talker

- bad mouth

- sharp mind

- take my hat off to …

- lend an ear

- lend (give) a hand

- show your face

- hard headed

- apple polishing