Ann Mayeda, Konan Women’s University, Japan

Dirk MacKenzie, Konan Women’s University, Japan

Brian Nuspliger, Konan Women’s University, Japan

Mayeda, A., MacKenzie, D., & Nusplinger, B. (2016). Integrating self-access centre components into core English classes. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(2), 220-233. https://doi.org/10.37237/070210

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

The Department of English Language and Culture at Konan Women’s University opened a self-access center in 2011. “e-space” was built into the department common room as part of a renovation project. Two full-time lecturers/learning advisors were hired to develop the language learning resources, offer advising services and to develop a more dynamic language learning community. In 2012, the department revamped its curriculum with a focus on improving the core English courses and facilitating the development of learner autonomy. Self-access language learning (SALL) activities were gradually integrated into the core courses as a way to expose students to the resources available in e-space and to provide opportunities to engage in language learning in a more learner-centered way. In 2013, teachers were asked to integrate SALL into first- and second-year core classes, and in 2014, these components became compulsory, graded sections of the courses. A stamp card system was developed to help students and teachers track the activities. At the end of the year, the cards were collected and student feedback was solicited via an online survey. While teacher buy-in has been difficult to achieve across the board, preliminary results show that the SALL components were generally successful in terms of student participation and satisfaction.

Keywords: self-access, learning spaces, curriculum

Context

e-space, the self-access center in the Department of English Language and Culture at Konan Women’s University (KWU) opened in 2011 as a part of the renovation of the department’s common room (CR). All departments in the university have a CR that serves as its administrative center to accommodate student needs within the particular department. Before the renovation, the English department CR housed a small graded reader bookshelf, some self-study resources and held lunchtime English sessions, or English Cafe, facilitated by international students and teachers. The decision was made to revamp this CR into a more fully functioning self-access center in order to better meet the needs of a more diverse student body and to promote autonomy in language learning. The expanded space allowed for a larger graded reader library area, more self-access materials, learning spaces, a dedicated advising room and language advising services. English Cafe sessions were increased and efforts were made to recruit student volunteers and hire student staff to help develop the “social learning spaces” (Murray & Fujishima, 2013). To facilitate this, two full-time lecturers were hired as learning advisors to focus specifically on developing e-space as a language-learning hub.

Integration of e-space use into the core English curriculum has been established in stages. In this paper, we look at this integration from the perspectives of the two learning advisors who also teach in the core English courses and a faculty member who oversees the general management of e-space.

Stages in Integration with the Curriculum

In 2012, the English department launched an initiative focusing on improving the core English curriculum and facilitating the development of learner autonomy. Changes were to affect one of the Production and Fluency (P&F) courses aimed at helping students develop communicative competence. The decision was made to integrate SALL activities into the courses in order to give students an incentive to make use of the available resources in e-space and encourage them to make language learning a part of their lives outside of the classroom.

The curricular changes were explained to all faculty members in 2013 at a special session. Course descriptions and outcomes were standardized, including the requirement to make use of e-space resources with a suggested 20% grade allotment. However, few teachers incorporated use of e-space into their course in the first year. Thus in 2014 the learning advisors created a stamp card system for introducing and tracking e-space activities and the 20% grade allotment became a requirement. While we were aware of the potential to derail intrinsic interest by adding this type of extrinsic reward system, after much discussion the advising team made the decision to move forward with it with the rationale that learners needed to experience the SALL components first, after which they would then be in a position to make an informed choice on whether to continue using them. In particular, we were aware that reluctant learners, even if they knew of the benefits of SALL, would not willingly come on their own.

The e-space Self-Access Components

The ten-space stamp card (Figure 1) was created to familiarize students with e-space and keep track of activities. Other centers have successfully used stamp card schemes for tracking and encouraging usage and attendance (Croker & Ashurova, 2012; Talandis Jr. et al., 2011). In addition, incorporating a percentage of course grades and teacher encouragement seems to have resulted in higher completion rates (Talandis Jr. et al., 2011).

Figure 1. Stamp Card

The P&F teachers were asked to collect the cards at the end of each semester and award two points for each stamp received. This constituted the 20% grade for the self-access component. After grading, teachers were asked to submit their students’ cards for record-keeping purposes.

Information session and learner profile

During the first two weeks of the spring 2014 semester, a learning advisor conducted a 45-minute e-space information session for each first-year P&F class. Students had an e-space tour and received instructions for using the stamp card (Appendix A). They were also given a learner profile sheet (Appendix B) and shown how to make an advising appointment online. Students were instructed to complete the profile sheet and to book their first advising session.

Advising

Twenty-minute advising sessions are available for students to discuss their language learning plans and goals. These can be short-term or long-term with the advisor helping the learner break them down into more realistic or manageable tasks. While each advisor may conduct their sessions differently, there is general consensus that students should come to advising for a specific purpose related to their language learning. This can be anything from questions related to vocabulary acquisition, improving listening skills, working on specific communicative tasks, or discussing issues related to motivation. The advisor might recommend strategies, resources, or offer different approaches to reaching their goals. Learners are encouraged to schedule follow-up appointments to check back on progress.

Four advisors are available in e-space with sessions offered daily from second to fourth periods including lunchtime with some exceptions due to scheduling. Two advisors conduct sessions in English and two conduct sessions in either English or Japanese.

For the stamp card advising session, students bring in their learner profile sheet and discuss their learner histories and what they hope to achieve by the time they graduate. It is an opportunity for the advisors to get to know the students and to inform them of the various resources available to them.

English Cafe

English Cafe has been running at lunchtime for several years. Since the renovation it has been expanded beyond the lunch hour several days of the week. Part-time teachers and international students from a nearby university are hired as conversation facilitators. In 2014, as part of the ongoing efforts to encourage ownership of the center, students in the department were asked to volunteer and several students were hired as e-space student facilitators.

Participation in three English Cafe sessions was required on the stamp card. While English Cafe has always been popular with a core group of students, it was added on the stamp card as a way to encourage reluctant students to try at least three sessions with the aim of lowering the affective barrier to entrance and encourage future unguided participation.

Activities and events

Participation in activities (Appendix B) and attendance at events in e-space rounded out the last four stamps. Students were free to choose activities and received a stamp after talking briefly with an advisor about what they engaged in. Lunchtime talks and seasonal events were announced periodically over the semester to encourage attendance.

What We Have Learned

Stamp cards

The stamp card system was implemented in 2014 with all first-year students participating in the first semester and second-years in the second semester, in order to stagger the demand on resources. Since 2015 only first-year students have used the cards as second-years had completed them the previous year and would already know what e-space had to offer.

At the end of the spring 2014 semester, 50% of the first year stamp cards were received from teachers (Table 1). The remaining 50% were either not submitted by students for grading, or not passed on by teachers after grading. Of the stamp cards that were returned, 93.3% were complete, indicating that the occasional student had submitted their card without getting all 10 stamps.

Overall, students have been consistent in completing the stamp card (around 93% each semester), and submission has improved steadily since the launch of the program, from 50% in spring 2014 to 87% in spring 2015.

While several classes had students who did not submit cards to teachers and a few where all students submitted, the larger issue was teacher non-compliance. Three teachers failed to turn in any stamp cards and one turned in only six out of twenty. One teacher did not collect nor grade the cards but these were collected later by CR staff. This data is included in the figures above.

Survey

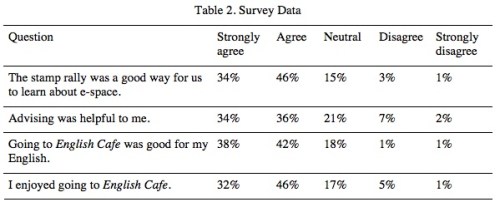

At the end of the 2014 academic year, all teachers were requested to administer a bilingual survey on the stamp card and the self-access component. The response rate for the P&F student survey was 60.7% overall, with 76.4% of first-year students and 44.8% of second-years completing it (Table 2). One first-year and four second-year teachers failed to administer the survey.

Respondents were generally positive about the SALL components of the course. They felt that the stamp card was a good way for them to learn about e-space, with 80% agreeing or strongly agreeing. They found advising helpful, but were not as enthusiastic as they were about the stamp card system itself as only 70% of students agreed or strongly agreed. English Cafe was popular, with 78% of respondents reporting that they enjoyed going and 80% believing that it was good for their English.

Advising

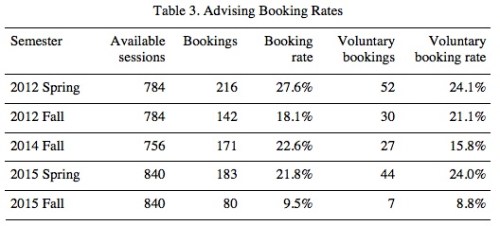

All first-year students since 2012 have been required to attend one advising session in the spring semester. Records show a range from 21.8% to 27.6% of available sessions booked during spring semesters (Table 3). This booking rate, while seemingly low, is not necessarily problematic when considering the total number of slots available to accommodate student schedules. Records show that most of the morning sessions are not booked due to classes in session or an unwillingness to come in early for an advising appointment.

Fall 2012 saw an 18.1% booking rate with no stamp card running. Fall 2014 had a 22.6% booking rate with one advising session required of second-year students as part of the stamp card task. In fall 2015, advising bookings dropped to 9.5%. (Unfortunately, data for 2013 and spring 2014 was not culled from the scheduling software and was lost.) A slight decline in advising appointments in the fall semesters is not unusual as we generally see a wane in overall enthusiasm after the summer break. The precipitous drop to 9.5% in fall 2015 is, however, a concern. This could be attributed to several factors: 1) it was a busy semester with many events running and an extra class shared between the two main advisors, which reduced the number of prime advising slots available; 2) unlike fall 2014 where all second-year students had required sessions via the stamp cards, there were few compulsory sessions; 3) while the advising stamp served to familiarize students with the reservation process and gave them the opportunity to discuss their learning profiles, a single twenty-minute session may not have allowed students to see the value of advising or even how it is meant to help with their language learning; 4) the non-voluntary nature of the first advising experience may have contributed to the decline. That is, “the learner may make a great deal of effort…when a reward is present; however, when it is removed, it is likely that the learner will quickly cease to engage in the learning process,” (Noels, 2013, p. 16). These factors may partially explain the low booking rate but it is an area requiring further attention and these numbers continue to be monitored.

Advising repeaters

Over the five semesters on record, 69.8% of the 792 students who have come to advising returned at least once. Most returnees have come twice (13.3%), three (13.6%), four (11.7%) or five (13.3%) times in total (Table 4).

Although second-year students completed the stamp rally in fall 2014, advising sessions had been required of all first-year students since 2012. This meant that for these students the required advising session via the stamp card task was actually their second. This may have lead to an increased understanding of the purpose of advising and the increase in repeat sessions later in the semester and into spring 2015 giving more weight to the notion that a single, twenty-minute session is not enough to understand the benefits of advising.

English Cafe

The number of students the teacher and student facilitators spoke with during their English Café shifts is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. English Cafe Attendance 2011-2015

Staff reported speaking to 610 students in the spring 2014 semester, 603 in the fall, and 726 in spring 2015. All three semesters had stamp cards running, in which some 150 students were required to attend English Cafe three times each. Interestingly, these semester totals are not much higher than in years previous to the stamp card (570 in fall 2011, 576 in fall 2012, and 575 in spring 2013, for example). Requiring students to attend English Cafe sessions has only resulted in a moderate increase. This could be due to seating limitations, as only so many students can join at any one time. 664 students participated in fall 2015 with no stamp cards running. It seems that the stamp card has had a positive impact on voluntary English Cafe attendance, although this will need to be measured over many semesters. In addition, while it is likely that the inclusion of English Cafe in the stamp card contributed to an increase in numbers of first time attendees, it is difficult to determine whether it contributed to repeat voluntary visits beyond the required three, or if regular participants continued to attend as usual.

Activities and events

As for activities and events, data has not been maintained on the type of activities the students have engaged in for the stamps. Numbers in attendance at events were tracked beginning in 2015. This ranged from 8-30 participants amongst 24 lunchtime talks and special events. However, there is not enough data on how many students required stamps at any one event, nor on the type of events that proved most popular.

On-going Challenges

Teacher buy-in

As most of the core English classes in the first and second year are taught by part-time faculty, the challenge has been to clearly communicate to the teachers the need for integrating SALL content into the bigger curriculum picture. Toogood and Pemberton, in reference to a talk given by Charubusp and Sombat (2006) state that, “One of the main hurdles [in integrating SALL into courses] was dealing with teachers who are unsupportive or ignorant of the concept of SALL” (2007, p. 185). This is compounded by the fact that most of the teachers have taught at this university for a number of years and are accustomed to a relatively high level of autonomy over course content. While communicating the need for more learner-centered components in their courses has been fairly straightforward, putting it into practice has been challenging, particularly since teachers were asked to adhere to a common syllabus. To illustrate, the P&F course has eight sections all taught by different teachers. Previously, there was a common course guideline but individual teachers decided on content, syllabi and textbooks. With the revision, textbooks were disallowed and teachers were required to have the same course description and outcomes to include the self-access components, and to then reserve a percentage of final grades to these components. This meant that in order to allow for more autonomy for the learners, teachers were being asked to give up some autonomy over their courses. Most teachers have been open to the changes while a few passively resist through non-compliance as is evident in the failure to submit the stamp cards and the low response rate to the survey.

Advice and Suggestions

While we are still in the process of working out the SALL components of the curriculum, the following are suggestions for those undertaking a similar endeavor.

- Support the teachers in facilitating the self-access components in the form of offering professional development opportunities or access to relevant professional journals. If the teachers do not understand the pedagogy behind autonomy, how can we expect our students to?

- Maintain contact. Since much of the responsibility falls on teachers to make sure students are on target; it is important that they understand the specific requirements and deadlines throughout the year

- Get feedback from the teachers. What support might the teachers need in order to integrate self-access and independent learning more successfully with the course content?

- Be patient.The process of information filtering down from the department to teachers to students requires several semesters to work out.

- Transition takes time for both learners and teachers. Asking students to engage in different ways of learning, just as asking teachers to make changes in their teaching, will not happen overnight.

Conclusion

While much of this paper has focused on the framework for integrating SALL activities into the curriculum, it is important not to lose sight of why we do this. Just as students should not be focused on collecting stamps but rather engaging in and understanding the intrinsic value of an activity, our focus should not be on how many stamp cards were turned in or how many advising sessions were booked as a measure of success but rather how all of this contributes to language learning in more deliberate learner-directed ways and ultimately for students to become more autonomous learners.

Notes on the Contributors

Ann Mayeda is a lecturer and teacher educator in the Department of English Language and Culture at Konan Women’s University. Her research interest focuses on learner development and issues surrounding autonomy as it applies to young learners and young adult learners. In addition to her teaching duties, she is on the learning advising team and oversees the management of e-space.

Dirk MacKenzie is a former lecturer and learning advisor in the Department of English Language and Culture at Konan Women’s University and served as vice-president of the Japan Association for Self-Access Learning from 2011 to 2016. His research focused on student usage of e-space and writing fluency. He has recently returned to Canada to continue his academic career.

Brian Nuspliger is a lecturer and learning advisor at Konan Women’s University. Since 2014 he has co-administered the activities of e-space. His research interests include motivation and the self-efficacy of teachers. He is also on the board of directors of the educational NPO e-dream-s.

References

Croker, R., & Ashurova, U. (2012). Scaffolding students’ initial self-access language centre experiences. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(3), 237-253. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep12/croker_ashurova/

Charubusp, S., & Sombat, T. (2006, March). Self-access learning as a support for English medium instruction. Paper presented at the Hong Kong Association for self-access learning and development, City University of Hong Kong.

Murray, G., & Fujishima, N. (2013). Social language learning spaces: Affordances in a community of learners. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 36(1), 141-157. doi:10.1515/cjal-2013-0009

Noels, K. (2013). Learning Japanese; learning English; promoting motivation through autonomy, competence and relatedness. In M. T. Apple, D. Da Silva and T, Fellner (Eds.), Language learning motivation in Japan (pp. 15-34). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Talandis Jr., G., Taylor, C., Beck, D., Hardy, D., Murray, C., Omura, K., & Stout, M. (2011). The stamp of approval: Motivating students towards independent learning. The Toyo Gakuen Daigaku Kiyo [Bulletin of Toyo Gakuen University] 19, 165-182.

Toogood, S., & Pemberton, R. (2007). Support Structures for Self-Access Learning. In A. Barfield and S. H. Brown (Eds.), Reconstructing autonomy in language education (pp. 180-195). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Appendices