Luke Carson, Hiroshima City University, Japan

Download paginated PDF version

Carson, L. (2015). Human resources as a primary consideration for learning space creation. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6(2), 245-253.

Abstract

This paper discusses language learning space creation within third level institutions in Japan – specifically self-access language centres (SALCs). Human resources are particularly important considering that language learning is, both a difficult task that can be facilitated through expert support, and a necessarily communicative, interactive endeavour.

It suggests that the first issue designers of new learning spaces may wish to consider is educational staffing, and gaining institutional approval for the necessary funding from the outset if possible. As the history of SALCs clearly shows, adequate and appropriate staffing remains key in order for optimal and broad learning gains to occur.

One of the earliest evaluative studies of SALCs was conducted by Gardner and Miller (1997) in Hong Kong. The finding of most salience to this discussion is that “the SAC manager’s post should be full-time as should some of the tutor’s posts” (Gardner & Miller, 1997, p. 118). As a non-traditional learning environment where student and ‘teacher’ roles are repositioned, a SALC does not function within the same parameters as, for example, a language classroom. SALCs tend to employ learning advising rather than teaching. “While both the disciplines of advising in language learning and language teaching attempt to improve students’ language competence and learning ability, and would generally state both as desired learning outcomes, the weighting given to each goal is different” (Carson, 2012, p. 247). Those involved in setting up and running a SALC need to bear in mind different factors, and have a different knowledge base and skills set. Or, at least, they must have the time to develop this new knowledge and skills set, which can be problematic if this role is merely an addition to a wider job role.

Author background

I have worked in different capacities with seven different SALCs, in Japan and elsewhere. I was a full-time learning advisor for seven years, and a full-time SALC coordinator for five years. I have had coordination responsibilities for SALCs as a small part of wider academic roles, and worked in an external consultancy capacity. I have varied experience of what a SALC can be, and how staffing situations in universities arise and impact the services than can be offered.

Although not exhaustive, and definitely a personal list, reflecting on my working experience, staff working full-time in a SALC (coordinators, learning advisors and administrative staff) can do the following:

- Become expert language learning advisors

- Develop positive relationships with a large student population of individual learners and sustain these relationships to allow learning to prosper

- Through understanding individual preference, bring enjoyment and creativity to learning

- Create materials and learning pathways specifically for independent learning

- Create materials and learning opportunities for the myriad of specific language learning related issues students may have

- Stay current with relevant educational developments

- Complement wider university teaching and learning endeavours

- Motivate and assist learners for whom traditional learners pathways are not so effective

- Infuse learners with an interest in learning and a sense of their own agency

- Develop the SALC as a hub of internationalisation within the university

While staff attached to SALCs on a part-time basis can indeed do some of the above, they cannot do all.

The Need for Academic Staffing: Case Studies

As the name suggests, students can use SALCs independently. In the case of Japanese university learners coming from directive learning experiences, this requires a new learning schema, and one that necessitates support as they begin to negotiate this beneficial but unfamiliar learning environment. Most students are not yet expert language learners. Technology programmes (e.g. Kidd & von Boehm, 2012), administrative support and peer systems do help. Yet, in these cases, the technology has to be designed and maintained, and the administrative and peer support staff have to be trained (preferably in an ongoing manner). Most importantly, none of these can provide the individualized expertise that a dedicated learning advisor can.

In order to understand how SALCs can be staffed (or indeed not staffed), three examples are given below of SALCs in Japan with different staffing situations, where I have had different levels of working involvement (the descriptions represent the situations at the time of my involvement and may have since changed).

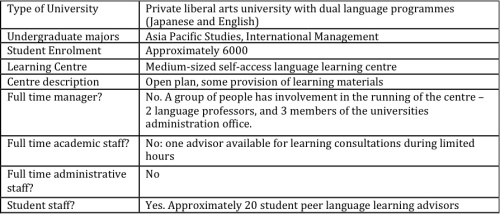

University 1

Table 1. SALC Situation in University 1

Why so well staffed? Although it is problematic to quantify the benefits of self-access learning (Morrison, 2005), and therefore difficult to make a financial case for its provision, this particular university was able to obtain external funding at the outset, as at the time of its inception it was an innovative project. At the same time, although quantifying its role as a revenue driver for the university was not possible, the university was also happy to fund the centre, as it understood it as a ‘loss leader’ (something that while not directly creating profit, drives wider profit to the provider). The centre became a major part of open campus tours for high school students, improving student enrollment. Being highly staffed, it developed excellent services. The centre became a central, supported and valued element of the university.

I was initially employed here as a full-time learning advisor, and later took on a managerial role. As a result of the large full-time staff, this centre provided a huge range of services – orientations to the SALC for all students in the university, semester-long independent learning modules all students could take with their own personal learning advisor (tailored to their stage of learning development or language need), drop-in advisory services all day, a reservation advising system, events, and a huge range of both purchased and in-house created language learning materials. The full-time staff were able to provide excellent services because the dedicated role allowed them time to do so, and time for ongoing training and development specific to this role.

University 2

Table 2. SALC Situation In University 2

Why this staffing arrangement? When this SALC was created, the management team did not include any members with specialist knowledge of independent learning or SALC management. The university administration office controlled funding for the SALC, and the employment of full-time staff was not considered. Student staff were employed as this was common across the university (through a teaching assistant system).

My involvement with this centre was short (providing cover for a professor who was on a leave of absence). After gaining consensus from colleagues involved, I attempted to make a case for full-time staff, even for one full-time advisor. I prepared a report outlining the needs of the students in the context, and how these needs are being effectively addressed in other SALCs that have full-time employees. This report was then sent to the main financial decision-maker, but unfortunately, the request was not approved. In fact, no reply was received.

Reflecting on this, my approach was somewhat naïve and shortsighted in its orientation. In this instance I did not have the social capital necessary to effect such a change, nor enough knowledge of the wider planning and activities of the university. At the time, the university was developing other aspects to promote active learning and the development of ‘global human resources’ (MEXT, 2012). Taking a longer, more contextually situated view – placing the SALC within these activities – may have proven successful.

University 3

Table 3. SALC Situation In University 3

Why no educational staff? In this university, the centre functioned with only an administrative staff member whose role was limited to lending materials for use in the centre, and managing the computing facilities. There had been no discussion of staffing the centre with learning advisors. The centre was created to provide a space for students to work on required language practice delivered through a CALL programme, and the chance to use extra language learning materials. As such, at the time of its creation, wider learning goals may not have been considered. With frequent changes of directorship, a clear plan did not develop.

Having a distant working association with this centre, when asked for some input – for example, suggestions for language materials to purchase – I found it difficult to answer with confidence. My main priorities were elsewhere and my knowledge of how students were using the centre was minimal. This made suggesting materials most appropriate to the specific context problematic – what language difficulties were these students having, what materials were they interested in using, what materials might encourage other students to use the centre? When I asked these questions, the information was not available. While I could use my past experience to inform my suggestions, doing so without context-specific knowledge or adequate time devoted to the process was not ideal.

Three different staffing arrangements are described above. Each centre provides valuable services to students, but the depth and breadth of services offered differ greatly – a direct result of the number of educational staff available, their understanding of self-access language learning, and whether or not this role is their main priority.

The Japanese university context: Academic Roles and Finance

Although it is globally common for faculty to be involved in various university activities, the degree and importance of this in the Japanese context is important to clarify. Tenured faculty members are expected to be teachers, researchers and ‘administrators’, unlike in many other international situations, where academics tend to move into one of these directions more singularly.

In his ethnography of a Japanese university faculty, Poole (2010) shows the perception of ‘good professor’ to be based on devotion to the place of work, exhibited through engagement in activities that have high ‘visibility’, such as university committee and ‘extra duty’ work. This creates a situation where faculty members expect and are expected to take on ‘extra duties’. Therefore, were a faculty member to suggest creating a new learning space, one could reasonably expect that the direction of this new space would fall under their remit, on top of their existing duties.

Faculty who become involved in SALCs on top of their base duties (or on a part-time basis with a reduction of other duties), can and do create excellent learning programmes and systems. Many universities have vibrant conversation lounges and student driven initiatives. Many organize peer-to-peer learning and peer tutoring programmes (as in the case of University 2) that have many benefits for students, though come with limitations (Boud, Cohen, & Sampson, 2014), and require coordination. If a centre is deemed ‘functioning’ under such a framework (as in the example of University 2 above), making the case for full-time staff is more complex. Making a strong case for this staffing at the outset, as part of a ‘SALC package’, may prove easier than asking for it later, when a SALC is already up and running under the ‘extra duty’ system.

Alongside the roles of academics, it is of value to know the financial workings of an institution. As learning centre creation requires funding, it is important to understand

- Budget categories (human resources, technology) and timeframes (e.g. an institution may function on a 6 year budget cycle)

- who the decision-makers are

- what the priorities of the decision-makers are

Take the case of University 3 given above. In this university, the number of faculty was being reduced. If my goal was to staff the centre with learning support, I would need to take a longer view – using the timeframe of the current budget cycle to garner university support, gain access to the most relevant decision-makers, and consider other options (i.e. if new tenured faculty appointments for the centre will not become possible, what about full-time term limited appointments?).

Conclusion

Although this paper makes the case for the full-time academic staffing of SALCs, that does not mean that such a space cannot be created without it. There are learning spaces developed and managed by very dedicated teachers with pre-existing full workloads that afford some excellent learning opportunities for students that would be unavailable otherwise. It is of course also possible (though perhaps more difficult, as the case of University 2 above shows) to begin such a centre without full-time staffing and seek the staffing at a later stage.

As exemplified in this paper, SALCs without full-time staffing arrangements provide fewer learning opportunities. This can leave the dedicated ‘part-timers’ facing an uphill battle in terms of their own learning curves, other work demands, and attempts to increase the staffing complement after a centre is up and running.

Following the four steps below from the outset may increase the likelihood of support for full time academic staff in a SALC:

- Clarify what services a fully staffed centre could provide, and why these roles are necessary (perhaps through a comparison of a well-staffed centre and a non-staffed centre)

- Find out who the academic members involved in the financial decision-making and educational planning of your university are, and which of these members are most likely to support your plan. Convince them of point one!

- Understand the budget cycles and limitations of your institution, and find out about university wide initiatives.

- Consider all the benefits a SALC can provide (beyond improved language competency), and which of these will appeal to the decision-makers. For example, in Japan, universities have been tasked with but are struggling to develop kokusaika (internationalization) (Breaden, 2013), kosei (individuality), ikiru chikara (‘zest for living’) and sozosei (creativity) (MEXT, 2013) – all of which a supported SALC may be positioned to facilitate.

Notes on the contributor

Luke Carson is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of International Studies at Hiroshima City University, where he teaches cross-cultural psychology, intercultural communication and education courses in English. His research interests are interdisciplinary approaches to understanding and improving learning, curriculum and learning environment design, and cross-cultural studies.

References

Boud, D., Cohen, R., & Sampson, J. (2014). Peer learning in higher education: Learning from and with each other. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Breaden, J. (2013). The organisational dynamics of university reform in Japan: International inside out. Abingdon, UK, Routledge.

Carson, L. (2012). Why Classroom based advising? In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.). Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 247-262). Harlow, UK: Pearson,

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1997). A study of tertiary level self-access facilities in Hong Kong. The Evaluation of the Student Experience Project. Hong Kong: Hong Kong City University. Retrieved from http://www2.caes.hku.hk/dgardner/files/2013/12/Gardner-Miller_1997.pdf

Kidd, K., & Von Boehm, S. (2012). Kaleidoscope, an online tool for reflection on language learning. In Mynard & Carson, (Eds.). Advising in Language Learning: Dialogue, Tools and Context (pp. 129-150). Harlow, UK, Pearson,

MEXT [Ministry of Education Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan] (2012). Project for Promotion of Global Human Resource Development. Retrieved from http://www.mext.go.jp/english/highered/1326675.htm

MEXT [Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan] (2013). Kyoiku shinko kihon keikaku [Basic Plan for the advancement of education]. Retrieved from: http://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/keikaku/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2013/05/16/1335023_002.pdf

Morrison, B. (2005). Evaluating learning gain in a self-access language learning centre. Language Teaching Research, 9(3), 267-293.

Poole, G. S. (2010). The Japanese professor: An ethnography of a university faculty. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.