Ashley R. Moore, Language Learning Center, Osaka Institute of Technology, Japan

Misato Tachibana, Language Learning Center, Osaka Institute of Technology, Japan

Moore, A. R., & Tachibana, M. (2015). Effective training for SALC student staff: Principles from experience. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6(4), 444-460.

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

Student staff can play a vital role in any Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) (Gardner & Miller, 1999; Cooker, 2010) and providing training for them is one of the key skills required of people managing SALCs (Gardner & Miller, 2013). This article charts the evolution over four years of a training program for student staff at the self-access language learning center at Osaka Institute of Technology in Japan. After detailing the institutional context of the center, we (the director and assistant manager of the center) discuss how, through a reflective process, the training program developed over this time period, moving from a group-based approach to a more individually-focused program. In the concluding section we draw on these experiences to put forward five principles that we believe will help others who are seeking to establish effective student staff training programs.

Keywords: self-access management, student staff, training, individualization of training

Context

Osaka Institute of Technology (OIT) is a university located in Osaka, Japan. It consists of three faculties: Engineering, Intellectual Property and Information Technology. The university has about 7000 undergraduate students and 500 graduate students. The Language Learning Center (LLC) was established in 2012 through a bilateral agreement between OIT and Kanda University of International Studies (also located in Japan). The LLC is a Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) but also provides various taught courses. The working mission of the center is to:

“ … create a self-access learning community in which OIT students, faculty members, and administrative staff of all proficiency levels can further their language learning. The LLC team wish to aid users in becoming autonomous, critically reflective, life-long language learners, and hope to support OIT in achieving its vision of developing globally fluent graduates who can thrive in the globalized workplace. Through collaboration with OIT professors and administrative staff, we hope to establish the LLC as a gateway to the international world.”

Institutionally, the LLC falls under the purview of the Academic Affairs office. The center is staffed by four full-time lecturers (one of whom, Ashley R. Moore, is the LLC director and co-author of this paper), one assistant manager (Misato Tachibana, co-author), and 16 student staff (see next section for more details).

The LLC offers many different kinds of services such as Consultation Room (15-minute conversation sessions with one of the lecturers), Free Conversation (a lunchtime English conversation session run by a lecturer and a student English Conversation Assistant), a structured Speaking Program (run through the Consultation Room), an Independent Learning Program (an advising program facilitated by the lecturers who have been trained in language advising), and an advising program for the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC). In addition, the lecturers provide non-credit elective courses such as a study abroad preparation course. Besides these services, students also have access to various English learning materials such as comics, grammar textbooks, etc. (see Language Learning Center, n.d., for further information).

LLC student staff

The student staff each work a two-hour shift once a week. They are currently divided into two roles: English Conversation Assistants (ECAs) and Reception Assistants (RAs). ECAs work with lecturers during Free Conversation to help users to participate in the interaction. The RAs’ (the main focus of this paper) primary duties are to help users in the LLC, staff the counter, and carry out administrative tasks when required. In the next section we chronicle the evolution of the training program for the RAs over the four years since the establishment of the LLC.

Evolution of the Reception Assistant Training Program

Year one

When the LLC first opened, we had a very short window within which to physically set up the center and train students (recommended as students with an interest in English by the English language professors at OIT) as RAs. A training session was somewhat hastily put together by the assistant manager and the director, and consisted of a one-off group meeting (conducted in English) in which we demonstrated their basic duties to the students and covered (through a combination of brainstorming and translation tasks) some potentially useful language that could be used by staff during interactions with users in the LLC. Once it was drafted, we also shared the LLC mission statement (see above) with students. A second group training meeting was also held at the beginning of the second semester in which we reiterated duties that were commonly being missed by the RAs and demonstrated the correct procedures for some administrative tasks, such as processing new materials. During this first year, we also received feedback from the OIT professors that one of the RAs was dissatisfied with the amount of English they could use during their shift as they were often working alone and asked to perform administrative tasks. This highlighted a number of issues; 1) a mismatch between the RAs’ expectations of the job and the occasionally mundane reality of running a SALC, 2) a lack of interaction between the student staff and the rest of the team (exacerbated by the fact that the RAs were mostly covering the reception counter alone), and 3) that we had not given the RAs sufficient ‘sanction’ to express their feelings directly to us if they were unhappy.

Year two

A small number of RA positions opened up, necessitating the organization of a recruitment drive and interviews (Appendix A). In addition to fairly standard interview questions, we took it as an opportunity to clearly explain certain aspects of the job (such as the fact that the role did not always involve speaking in English for an entire shift) that, as discussed above, had led to occasional dissatisfaction amongst the first cohort of RAs.

Based on our experiences during the first year, it became apparent that a single group training session at the beginning of each semester was insufficient, as Connell and Mileham (2006) and Neuhaus (2001) have also found. In fact, a number of basic duties were being routinely missed by some RAs and so a follow-up group training meeting touching on these issues was held in the middle of each semester. These training sessions were increasingly conducted in Japanese (the first language for most of our student staff) as we found that the RAs tended to understand our expectations and instructions more clearly.

As set out in our mission statement, one of our goals was to build a ‘self-access learning community’ or Community of Practice (CoP) (Wenger, 1998) through the LLC. However, working conditions for the student staff largely prevented them from developing, following the CoP model, any sense of mutual engagement, joint enterprise or shared repertoire amongst themselves. In an attempt to provide a forum through which the students could communicate, we set up a Facebook group and made it part of the RAs’ basic duties to post in the group and read others’ comments. This proved to be ineffectual however, as although some RAs used Facebook, many did not. The fact that the interaction was prescribed also meant that when it did take place, it was often forced. We came to realize that a successful CoP cannot be cultivated by making membership a duty.

Year three

In the third year of the project, there were three major changes in terms of the LLC student staff. Firstly, we expanded our services to include the Free Conversation sessions. This gave us an opportunity to create the ECA positions (see above). This raised the number of student staff to 16, and created two groups with quite separate training needs. Secondly, as we spent more time with the students, we came to see them, not as a homogenous group, but as individuals with their own interests and skill sets. In addition to their basic responsibilities, we created individual roles for each RA to match their particular skills:

- Eco-Supervisor (taking care of the plants in the center)

- Social Networker (promoting the LLC through various social networks)

- Translator (translating various documents between English and Japanese)

- Graphic Designer (creating various graphic products for the LLC, e.g. posters)

- Display Supervisor (creating and maintaining shelf displays)

With this diversification of roles it became clear that there was a need for regular individual training. This resulted in the third major change: OIT agreed to allocate 90 minutes per week in the director’s schedule for individual student staff training meetings. Each student participates in three 30 to 45-minute meetings per semester. These meetings are co-facilitated by the director and the assistant manager.

At first, these individual meetings were loosely structured around the following questions:

- Do you have any questions about your work?

- Do you have any ideas for improvements that could be made to the LLC?

- What are your professional goals?

- What do you want to achieve before our next meeting?

When it was needed, we also used these meetings as a chance to offer supplementary training for those students who were having difficulties. Knowing that our student staff lacked opportunities to interact with each other, the second meeting during the second semester was run as a focus group between three to four students, during which we gave them time alone to introduce themselves, discuss what they enjoyed about their work and, most importantly, how they thought the LLC could be improved. We joined the group towards the end of the meeting and the students (perhaps emboldened by the opportunity to combine their voices) summarized their ideas to us. Many of these ideas (such as changes to the layout of the center) were implemented. These focus groups, along with the fact the student staff had taken it upon themselves to form a group through the LINE social networking app (crucially, this interaction was not ‘enforced’ by us and the platform was one that was already popular among the students), meant that a CoP finally appeared to be forming, driven by the student staff themselves.

Over the first 12 months, these meetings proved to be successful. However, there were a number of issues with the new training system. The open yet repetitive structure of the individual meetings meant that they began to lose some of their initial effectiveness. Related to this, we identified a need for a wider variety of more focused ‘User Support’ training sessions, crucial given that the RAs usually work alone and thus, as Beile (1997) has noted, ‘their performance can have an inordinate impact upon the center’s reputation’. Lastly, the hurried notes made during each training meeting were often hard to make sense of several weeks later. Like Connell and Mileham (2006), we found that a more robust system for tracking the individual progress of sixteen student staff was needed.

Year four

In our current year of operation the increased individualization of the RA role has begun to reap rewards, and we have watched with pleasure as the students have taken larger ownership over their roles within the center. For example, Shunsuke (pseudonym), one of the Eco-Supervisors, brought in a project that he had been working on at home: a 10-page guide on how to care for the various plants within the LLC, written completely in English. He explained how he had wanted to make sure the knowledge he had built up was passed on to future Eco-Supervisors once he had graduated. It has become clear that many of our student staff are now ready to take on a mentoring role for others. As trainers, we also need to recognize that student staff need support as they transition into a mentoring role. During Shunsuke’s training meetings, we are providing feedback on his English and encouraging him to think critically about how to improve the text as a training tool for others.

This year we have tried to introduce a phase of more focused ‘User Support’ individual training sessions, and have created sessions in which we discuss the key features of excellent user support and then perform a role-play with the student staff member ‘acting’ as themselves, one of us acting as a user and the other taking observations on the student staff’s performance (Appendices B & C). After the role-play, we discuss our observations, praising the student as much as possible, while also identifying areas where they could improve for next time.

Through the course of these training sessions, we were surprised to find that many students did not recommend services or materials that obviously suited the ‘user’s’ needs. We discovered a common reason behind the omissions: the student staff lacked key knowledge about some LLC services and materials because they had never personally used all of them. Thus, we have realized that a major phase of training has been missing from our training program: an early focus on ‘Knowledge Building’. To this end, during a student’s first semester of work, we are now asking them to work through a checklist of the most popular LLC materials and services (Appendix D) to ensure they have experienced them.

At the end of the third year we had noted the need for a more robust information management system for the training meetings. This year we have started using a simple database through Google Forms. Data is entered after each training session. As a result, the notes are more detailed and coherent (as they are written after, rather than during, the meeting) and we are better prepared for subsequent meetings. The database notes (see Appendix E) from previous meetings are shared with each student (and are written in a tone that bears this in mind), and we feel that the amount of detail included and ‘permanency’ of them being recorded in the database, send a strong message to the students that the training is important and we are invested in their development.

Five Principles for Effective SALC Student Staff Training

Having detailed the development of the RA training program in response to various challenges, in this concluding section we consider future directions for the RA training program, before putting forward overarching principles for effective SALC student staff training.

It is important to note that the RA training program is still very much a work in progress. From April 2016, our main objective is to provide more opportunities for experienced RAs to act as peer mentors in the training of new RAs. For example, we have asked the student featured in Appendix E to provide an example tour to new RAs during the initial group training session. In terms of support, we have been providing extra feedback and practicing the tour with the student in order to build his confidence as a mentor. A further objective is to consolidate the training program into a series of distinct phases (see Principle 2 below) and produce a training manual that each student will gradually work through, with acknowledgement of their achievements as they progress. We offer the following five principles that, based on our experiences, can guide those wishing to implement or refine similar programs.

- Recognize each student as an individual and tailor their roles and the form and content of their training accordingly

Over the years, we have moved towards an increasingly individualized style of training for our student staff, and have seen a host of benefits. Observing each student staff’s learning style and adapting one’s approach accordingly can aid understanding. For example, some students only need a simple description of their duties and an explanation of the purpose, while others may have a more visual or kinesthetic learning style. In terms of language we have found that using Japanese in some cases can be more effective and lead to fewer misunderstandings. Managers should also acknowledge that each student will bring a different skill set to the center, and create space within the student’s role in which they can show initiative and utilize these skills. Though we have been extremely fortunate to have been given officially designated time in our schedules to provide individual meetings, those without such affordances should note that we also provide training during the RAs’ shifts. Ensuring that there is sufficient time in each student’s shift when they are working alongside others should provide ample opportunity for individualized training.

- Identify and prioritize different training phases

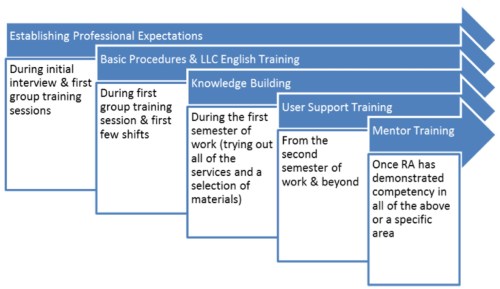

SALC managers should identify the micro skills and knowledge required of student staff and group them into prioritized phases. The creation of such a system ensures that the training provided is timely and that every student eventually completes all of the training phases. This is especially important if, as we would recommend, the training is individualized as much as possible. Other contexts may find different phases more appropriate, but the current LLC training program has coalesced into the phases shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Phases of the RA Training Program

- Create effective data management systems

Any ongoing training program, and in particular those which are individualized, will require a reliable and intuitive data management system. Systems such as Google Forms help trainers to ensure that the support they provide is efficient and effective, while the fact that the data is electronically stored enables trainers to quickly check a particular student’s progress over several years and maintain institutional memory.

- Facilitate (but not enforce) the development of a Community of Practice amongst student staff

A great deal of the training and learning that takes place in any group happens informally between peers. The formation of a successful CoP among student staff will enable this kind of training and resultant relationships are often instrumental factors in terms of keeping team members happy and fulfilled at work. However, trainers should critically assess whether the ways in which students work are conducive to the development of a CoP. Where they are not, efforts should be made to encourage student staff to find a forum for communication that works for them. Furthermore, we have found that these forums tend to work best when managers maintain a mostly ‘hands-off’ approach.

- Be conscious of power dynamics and whether student staff are afforded the ‘right to speak’

In our experience, many of the best results emerging from the student staff training program have stemmed directly from instances when students have been given the space to give feedback about their roles and the ways in which the center is run. Moreover they must also feel empowered enough to do so. It perhaps goes without saying that these affordances cannot be assumed. Rather, trainers and managers must create them. We suggest finding ways for students to take more individual responsibility and facilitating focus groups and individual training sessions as possible steps towards such empowerment.

While we hope that these principles will be useful to others, we intend to continue developing the LLC student staff training programs and adding to this list in the future.

Notes on the contributors

Ashley R. Moore is the director of the Language Learning Center at Osaka Institute of Technology. His research interests are in identity and language learning, self-access management, and English for specific purposes. His work has been published in TESOL Quarterly and as a chapter in The applied linguistic individual: Sociocultural approaches to identity, agency and autonomy (Equinox, 2013).

Misato Tachibana is the assistant manager of the Language Learning Center at Osaka Institute of Technology. Her research interests include self-access management, staff training and using qualitative data from SALC users to inform development of the center.

References

Beile, P. M. (1997). Great expectations: Competency-based training for student media center assistants. MC Journal: The Journal of Academic Media Librarianship, 5(2). Retrieved from http://wings.buffalo.edu/publications/mcjrnl/v5n2/beile.html

Connell, R. S., & Mileham, P. J. (2006). Student assistant training in a small academic library. Public Services Quarterly, 2(2/3), 69-84. doi:10.1300/J295v02n02_06

Cooker, L. (2010). Some self-access principles. Studies in Self-Access Learning, 1(1), 5-9. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun10/cooker/

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (2013). The management skills of SALL managers. Studies in Self-Access Learning, 4(4), 236-252. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec13/gardner_miller/

Language Learning Center. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.oit.ac.jp/japanese/gakusei/llc.html

Neuhaus, C. (2001). Flexibility and feedback: A new approach to ongoing training for reference student assistants. Reference Services Review, 29(1), 53-64. doi:10.1108/00907320110366813

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511803932

Appendices: See PDF version