Introduction

Katherine Thornton (Column Editor), Otemon Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan

As the social dimensions of learning in general and learner autonomy in particular are being given increasing attention in recent years, Michael Allhouse’s column about the re-invigoration of the self-access centre (SAC) at his institution as a social learning space is an interesting insight into how these theories of learning can be applied to the field of self-access. In this instalment, Michael discusses some research that has been conducted into student reactions to this new approach to self-access provision

Researching the New Room 101: “A Safe Haven for Me to Learn”

Michael Allhouse, University of Bradford Union, UK.

Allhouse, M. (2014). Researching the new Room 101: “A safe haven for me to learn.” Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(4), 466-479.

Download paginated PDF version

The Self-Access Centre (SAC) at the University of Bradford (UoB), in the UK, is called Room 101. Over the past ten years Room 101 has adapted its approach, moving away from providing materials-based resources like books and CDs and becoming a social learning space; a space where students learn from each other in person, through interaction-based activities. These activities are sometimes in structured and sometimes in unstructured environments. Materials-based activities (paper-based, CDs or software) are mostly completed alone. Interaction-based activities (such as discussion clubs and informal social interaction) focus less on formal learning and more on interacting and communicating in English (or another language).

The previous instalment of this column examined how Room 101 had seen usage decline as a result of the closure of foreign language courses and the widespread provision of learning resources on the Internet. It outlined how Room 101 settled on an interaction-based / social learning approach, which has reinvigorated the centre.

Even though Room 101’s social learning approach was developed primarily as a result of engaging with student feedback, it was not until 2013 that any research into student reaction to the approach was conducted. The research aimed to measure which services provided by Room 101 students most valued, and to analyse the extent to which materials-based activities and interaction-based / social learning activities were seen as attractive by students. This instalment of the column focuses on this research.

Room 101 hosts a range of interaction-based / social learning activities. An example of one of our structured sessions is the debating club which meets every Wednesday for two hours and covers a range of topics. The session is run by the writer of this article and is focussed on giving international students (whether on English language courses or mainstream courses) English speaking practice so that they become more confident in their English use (usage of Room 101 includes students on English language courses, but during the time of this research attendance on such courses was low, meaning that most Room 101 users were international students studying mainstream courses). An example of another social learning activity is IELTS speaking practice which follows the format of an IELTS speaking test.

Less structured interactions also take place daily in Room 101 with full-time staff and student volunteer staff being encouraged to engage users in conversation in English. Room 101 also regularly holds cultural parties like Christmas parties, Chinese New Year parties, national day celebrations, and regular afternoon tea sessions. These events are attended by students from many different nationalities, meaning that they promote social interaction amongst peers in English.

Research Methodology

The research discussed in this instalment is mainly centred on a survey of Room 101 users, and a focus group conducted in 2013. The questionnaire was created using a webpage called Surveymonkey which was then distributed electronically.

The survey targeted international students who had used Room 101 to ensure that the sources of information were experienced in the topic (Polkinghorne, 2005). Selecting respondents who are relevant to the research study is known as purposive sampling. Purposive sampling can mean however that respondents might have some bias in favour of the provision (Maxwell, 2005). In order to maintain a purposive approach the survey was distributed via Facebook, requesting that only users of Room 101 fill out the survey. Facebook was a valuable tool as Room 101 already had a very engaged community on this social media platform.

Since the main aim of the questionnaire was to explore students’ reactions to Room 101’s new approach, the questions were focussed on determining the elements of Room 101’s provision which students valued most. The questions assessed what students valued, what else students would like, and how Room 101 could be improved. The questions were piloted in a focus group of regular Room 101 users, to examine whether they were clearly stated. No amendments were made as a result of the focus group.

It was important that the questions were student-friendly and simply stated, with the questionnaire being easy for students to fill out, as this allowed for promotion of the survey over social media as, ‘it will only take a minute to complete’, which ensured a large number of Room 101 users would complete the questionnaire. Over a two week period 75 users attempted the survey, although not all users completed every question.

The survey questions were:

- Of the following services provided by Room 101, please state how often you use each one. (list of choices)

- What else would you like to see in Room 101? (list of choices)

- What do you like most about Room 101? (open question)

- How can we improve Room 101? (open question)

- What course are you studying / did you study at the University of Bradford? (open question)

Question 1 asked how often people used various services and gave a number of options which were derived from a list of possible SAC activities. This list was populated using suggestions for SAC activities from the works of Little (1989), Gardner (2000b), McMurry, Tanner, and Anderson, (2010), Morrison (2005), and Del Rocío Domínguez Gaona (2007), which could be seen as primarily materials-based SAC activities. The list also included activities from the research of Croker and Ashurova (2012) which can be seen as interaction-based. The interaction-based / social learning activities provided by Room 101 were also included in the list. It was possible to conduct all of the activities in the list in Room 101.

The list of activities can be seen in Table 1. The Table is divided into three columns: ‘materials-based activities’, ‘interaction-based activities’, and ‘other activities’ which do not fit these two categories.

Table 1. Materials-based and Interaction-based Activities in a SAC.

In Question 1 respondents were asked how often they use each service from the list and were given several possible answers on a rating scale of 1 to 5, in order to ascertain frequency of use. The students could respond from ‘never using a service’ (1), to using it ‘many times each day’ (5). A table of the results (Table 2) can be seen in the next section.

Question 3; ‘What do you like most about Room 101?’ and 4; ‘How can we improve Room 101?’ resulted in answers which were limited in range and could be grouped according to a number of themes. Using grounded theory analysis (using categories which emerged from the data) (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) the answers were coded into a limited number of categories which could then be analysed.

After the collection of the questionnaire data a focus group of students was formed to address the findings. Fifteen students who had all completed the survey and were regular users of Room 101 took part in a two hour session led by the author of this column. Questions for the Focus Group can be found in the Appendix.

Results and Observations

Survey results

The first question in the survey, ‘Of the following services provided by Room 101, please state how much you use each one’, attempted to get some frequency of usage data. Table 2 shows how often the students state that they access each activity (not all students answered this question).

Table 2 shows that the activities which got the highest number of (code 5) responses were relaxing, socialising, and using computers for pleasure. The least popular activities (highest number of (code 1) responses) were using materials-based resources and equipment (tape recorders, DVD/CD players, materials created by Room 101 staff) for language (and particularly English) learning, attending English classes, and the one-to-one writing sessions with language staff.

A limitation of this research is that the figures need to be contextualised, as some events, for example Debating Club only happen once a week, so for students to rate it higher than (3) is difficult. However, in the ‘use once a week’ (3) section it scored highest. Other activities, like using books / CDs can be done all day, every day. Some activities, like writing help are done one-to-one so very few people can attend this in comparison to something like using the Internet to learn English, which can be done by many people at the same time.

Table 2. Results of the Question ‘Of the following services provided by Room 101, please state how much you use each one’.

As materials-based SAC activities were the activities most likely to be ‘never used’ (using tape recorders to practice language, using foreign language books and CDs, using English language learning books and CDs, using English language material specially created by Room 101 staff), it can be suggested that students no longer value Room 101 for its opportunities to use materials-based resources. The most popular activities (5) were socializing, relaxing and (factoring in the limited availability) facilitated interaction-based activities like the Debating Club. It can be suggested that students most value most highly the ability to practice English by socialising with other students and staff (interaction-based activities).

Observations of Room 101 usage from the 2011 Annual Report show that interaction-based activities were also popular in Room 101 at that time (Figure 1). The data in Figure 2 was based on observations over a week long period in 2011. Over the course of the week all students entering Room 101 were observed and sometimes briefly questioned to discover their reasons for using Room 101. Figure 1 shows that materials-based activities such as ‘using 101 language resources’ (any materials-based language practice including CALL and internet language learning was categorised as ‘using 101 language resources’) were less popular than social learning activities. ‘General working on computers’ in this survey was taken to be working on essays for mainstream courses or browsing for enjoyment.

Figure 1. Findings From Observation Research in 2011 About Room 101 Usage

Question 2 was an attempt to address the gaps in Room 101’s provision and to ascertain if students want more interaction-based activities or more materials-based provision. The question asked was: ‘What else would you like to see in Room 101?’ A list of choices was given. The most popular responses are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The Results of the Question ‘What else would you like to see in Room 101?’

The most popular responses were more social and cultural events, clubs, and more speaking practice. It can be said that it was interaction-based activities that were most requested, as well as more 1-to-1 writing help sessions. There were few requests for materials-based activities such as English resources and language software.

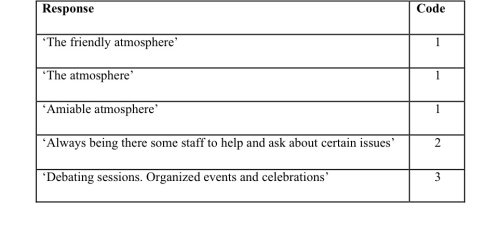

Question 3 was an open-ended question; ‘What do you like most about Room 101?’ The responses were coded according to the following three categories used a grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1998):

- CODE 1. Friendly and relaxing place – 33 responses

- CODE 2. Helpful staff – 26 responses

- CODE 3. Social learning activities – 10 responses

Table 3 gives a few examples of the responses.

Table 3. Examples of Coded Responses to Question ‘What do you like most about Room 101?’

Table 3. Examples of Coded Responses to Question ‘What do you like most about Room 101?’

The particularly high response rates for ‘Friendly and relaxing place’ and ‘Helpful staff’ demonstrate that students value the friendly atmosphere most, i.e. the informal use of Room 101 for speaking and socialising. There was no mention from any of the respondents of any materials-based activities.

In the answers to this question students repeatedly referred to the value of being able to practice their English in an informal setting:

“The friendliness of the place where you can find someone to have conversation with for English practice.”

“I found Room 101 was a place which encouraged me to talk more English and which really helped me to improve my confidence. It is friendly there so I feel encouraged and don’t mind making mistakes.”

Some responses were particularly interesting, such as the following:

“During my three years in Bradford, I have made Room 101 as a safe haven for me to learn about the local culture and exchanging knowledge of other culture from other foreign peers. Room 101 made me more curious about my surroundings and I guess, made me into a very open-minded individual. It is also due to the staff who would listen to us even though our grip of the English language was poor.”

Whilst friendliness, helpfulness and encouragement may seem only weakly related to language learning in SACs, there are some connections: Schumann’s acculturation theory (1978) states that engaging with a culture and feeling at home is strongly related to language acquisition. In Room 101 students are socialising with home students and staff (as well as people of other nationalities) in English, and are engaging in activities around British culture (such as informal workshops on British culture and culture shock, as part of our workshop programme). All of this helps acculturate students to their environment and encourages engagement with the language.

The friendly atmosphere of Room 101 can also be said to relate to Krashen’s (1987) theory of the lowering of the affective filter, in that students feel confident to enter the room, engage with activities and engage with English because of the friendly, supportive atmosphere.

The next question in the survey was; ‘How can we improve Room 101?’ The responses could again be grouped according to grounded theory coding into categories, as follows:

- CODE 1. More social learning and cultural events – 15 responses

- CODE 2. Increase awareness of Room 101’s provision – 9 responses

- CODE 3. Operational improvements – 3 responses

- CODE 4. More 1-to-1 writing help sessions – 2 responses

Table 4 gives examples of the responses.

Table 4. Examples of Coded Responses to Question ‘How can we improve Room 101?’

The answers to this question strongly suggest that the social and cultural elements of the room are what the students really value. Users did not demand more materials-based, language learning resources. Indeed, no respondent mentioned materials-based activities, but many mentioned having more social learning activities. This, in combination with the results of Question 2; ‘What else would you like to see in Room 101?’ show that more social learning clubs and cultural events are the most requested elements of Room 101.

The answers to this question strongly suggest that the social and cultural elements of the room are what the students really value. Users did not demand more materials-based, language learning resources. Indeed, no respondent mentioned materials-based activities, but many mentioned having more social learning activities. This, in combination with the results of Question 2; ‘What else would you like to see in Room 101?’ show that more social learning clubs and cultural events are the most requested elements of Room 101.

Focus group findings

A month after the completion of the survey, in order to further explore its findings and look at whether students prefer materials-based or interaction-based activities, the writer of this column conducted a focus group. A number of questions about what users like to do in Room 101 and about language learning were asked. There was discussion around the issues which arose.

There was a set list of questions for the focus group (see Appendix), which focussed on the same issues as the questionnaire, but went in to more detail. The focus group mostly confirmed the conclusions of the survey, in that the group spoke passionately about the social learning activities and the use of Room 101 as a friendly space for international students. The group did not mention the material-based resources as an attraction for them, or as something they had used.

When asked about how they like to learn English the group unanimously said practicing speaking and listening through conversation and social interaction. When asked why they don’t use the book / CD resources in Room 101 they said it was because there was sufficient practice material on the internet and because they did not have the time – having too much other work to do. When they were asked about practicing their reading and writing skills they said they knew there were classes for this at the university and workbooks available in Room 101, but again they didn’t have the time to use these or to attend the classes. This finding is similar to the finding by Klassen Detaramani, Lui, Patri, and Wu, (1998) that students acknowledge the value of extra study workshops but rarely actively chose to attend them, citing lack of time as the main reason.

Conclusion

The research discussed in this instalment has looked at whether the new, social learning approach of Room 101 is attractive to students. By asking students what services they value and what services they would like, the research attempted to assess if students want materials-based or interaction-based activities. The survey and focus group both showed that interaction-based / social learning activities are more attractive and more used than materials-based activities in Room 101. Students clearly value the room as a space to socialise and relax, as well as engaging in structured social learning activities such as debating group and specific cultural events. Students do not seem to want to use materials-based resources in Room 101, nor seem particularly interested in this as a way of improving their English.

There are several limitations to this research which should be acknowledged. The study is relatively small, and it is necessary to be aware of the researcher effect in the focus group which may have biased the group to be more positive about Room 101’s social learning focus. The research also only addressed frequency of usage and what students wanted more of; it did not look at effectiveness in terms of language acquisition of either materials-based or interaction-based activities. This could be an area of future research.

Room 101’s social learning success raises questions about the ability of materials-based resources to attract students to SACs. The next instalment of this column will describe the administration of a survey of SAC managers in the UK in 2013 which assessed how their provision had changed in recent years and what elements of their provision were most popular with students. The instalment will attempt to examine the extent to which the experiences of Room 101 are typical of the sector.

Notes on the contributor

Michael Allhouse has worked in Room 101 for almost 18 years, longer than Winston Smith, Paul Merton, Frank Skinner and O’Brien put together. He was awarded International Student Advisor of the Year 2014 by UKCISA / NUS. He works for the Student’s Union at the University of Bradford and is designing other social learning spaces for specific groups of students.

References

Croker, R., & Ashurova, U. (2012). Scaffolding students’ initial self-access language centre experiences. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(3), 237-253. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep12/croker_ashurova/

Del Rocío Domínguez Gaona, M. (2007). A tutoring system implemented in the Self-Access Centre in the Language School at UABC, Tijuana, Mexico. Humanising Language Teaching. 9(6). Retrieved from www.hltmag.co.uk/nov07/mart01.htm

Gardner, D. (2000). Making self-access centres more effective. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong. Retrieved from http://celt.ust.hk/files/public/3b161-174cases.pdf

Klassen, J., Detaramani, C., Lui, E., Patri, M., & Wu, J. (1998). Does self-access language learning at the tertiary level really work? Asian Journal of English Language Teaching. (8). 55-80. Retrieved from http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/ajelt/vol8/art4.htm

Krashen, S. (1987). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. London, UK: Prentice-Hall.

Little, D. (1989). Self-access systems for language learning. London, UK: Centre for Information on Language Teaching & Research.

Maxwell, J. (2005). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. London, UK: Sage.

McMurry, B, L., Tanner, M. W., & Anderson, N. J. (2010). Self-access centers: Maximizing learners’ access to center resources. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(2), 100-114. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep10/mcmurry_tanner_anderson/

Morrison, B. (2005). Evaluating learning gain in a self-access language learning centre. Language Teaching Research, 9(3), 267-293.

Polkinghorne, D. (2005). Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 52(2), 137-145.

Schumann, J. (1978). The pidginization process: A model for second language acquisition. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, second edition, London, UK: Sage Publications.

Appendix

Focus Group Questions

- What’s the best thing about Room 101?

- What do you do in Room 101?

- What other things could we do in Room 101?

- How do you like to learn English?

- How do you like to practice your English?

- Do you use the materials-based resources in Room 101?

- Why don’t you use the book / CD resources in Room 101?

- Do you attend Language Centre reading and writing skills classes? (if not, why not?)

- What more could the University do to help you improve your English?

- Do you think the interaction-based activities in Room 101 help you with your English learning / English confidence?