Kerstin Dofs, Christchurch Polytechnic Institute of Technology, Christchurch, New Zealand

Dofs, K. (2013). Giving speaking practice in self-access mode a chance. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(4), 308-322.

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

Finding resources and activities which will interest students and promote speaking in a self-access resource can be challenging. This article describes how the School of English at Christchurch Polytechnic Institute of Technology (CPIT), Christchurch, New Zealand, works to enable speaking practice in their Language Self Access Centre (LSAC). The activities which students are encouraged to do were produced consequent to research and an examination of good practice world-wide within the field of autonomy in language learning. The article will explore some basic design principles and conditions which were followed with the aim of creating maximal “comprehensible outputs” for speaking (Anderson, Maclean & Lynch, 2004), and, at the same time, creating conditions for these speaking tasks which would optimise development of autonomous language use (Thornbury, 2005). This is followed by an analysis of how the resources provided in a designated speaking area in the LSAC fulfil these principles and conditions, and how they may foster autonomous learning.

Keywords: speaking practice, support, autonomous learning activities, autonomous performance, task design

Speaking Practice: The Rationale

Self-access centres (SACs) dedicated to promote language learning typically stock it with resources for all skills, as well as for improving grammar and vocabulary. Providing resources for reading, writing, listening, and even for pronunciation of discrete vowels, consonants, vocabulary and sentences usually poses no particular problems; however, setting up provision for the development of spoken communication skills in a self-study situation is not as easy. First of all, speaking requires a partner and secondly, some ‘noise’ is unavoidable when practising and this may disturb others who prefer a more quiet study area. Authentic speaking practice, in which students become aware of and understand: purpose, level of formality, appropriateness, and strategies for discussions and conversations, may also be difficult to achieve in a SAC. Nevertheless, improving speaking seems often to be one of the most pressing needs for many of the English as an Additional Language (EAL) learners. Despite its challenges, providing speaking opportunities in a SAC can certainly, as this article will show, be addressed in many ways.

This article will analyse Language Self Access Centre (LSAC) speaking support for students in the School of English, at Christchurch Polytechnic Institute of Technology (CPIT) in Christchurch, New Zealand. It will firstly outline some theories and ideas around provision of autonomous learning support, and then compare these with the expected outcome of students doing some of the speaking activities offered in the LSAC.

The School of English caters for around 400 students per year originating from a range of non-English-speaking countries and educational backgrounds, with the most coming from the Middle East, China, Korea, and Japan. Their reasons for studying English in New Zealand varies a lot, from international students who want to improve their general English for further studies or work in their home country, to immigrants and refugees who have started new lives and therefore need to reach a satisfactory English language level for participation in New Zealand society. Most of them have had very limited previous opportunities of authentic speaking practice in English.

Theories and Ideas

With regards to ‘noise’ as a disturbance in a self-access centre, Gardner & Miller (1999) point out that the centres typically accommodate both for individual studies and for small group studies, depending on the learners’ choice, so noise as a result of speaking activities should be tolerated. To reach an acceptable sound level, they suggest the following actions: explain the necessity for noise in speaking to both students and staff members; encourage speaking practice within designated areas; raise awareness amongst the students so they can adjust their sound level if necessary; provide controlled speaking activities (taking turns, etc.); promote reflection on learning, as well as chatting in the target language, and finally, create an environment which discourages students from chatting in their own language.

A range of good practice ideas for speaking emerged from a study conducted by Dofs & Hobbs (2011). These include, for example: conversation clubs or classes run by student peers; focussed speaking practice determined by students’ choice; language exchange schemes; workshops run by staff; language computer software for pronunciation practice, and, most importantly, suitably resourcing a designated speaking area.

Figure 1. Suitably Equipped Language Practice Space at CPIT

Anderson, Maclean, and Lynch (2004) argue the case for pushing learners to produce “comprehensible output” (Swain, 1985). To create the necessary impetus for this ‘push’ they suggest the creation of speaking materials based on research and design principles which pay particular attention to five areas:

- “Comprehensible input” (Krashen, 1981) – learners have to mutually adjust their output to make the interaction and input comprehensible.

- Conversation involves both knowledge development and problem solving in the target language.

- Learners need practice in divergent talk, i.e., a common speaking goal is not present (e.g. role plays)

- Assessments should focus on students’ ability to get the message across and not only on accuracy.

- Tasks should be repeated with different partners so learners are given a chance to interact with more than one other learner and thereby improve their speaking performance.

According to Anderson, Maclean & Lynch (2004), the materials writer should, when designing tasks for speaking, include scenarios in which the speakers have different personal goals so that the tasks involve unpredictable interactions and thereby emulate real-life situations. They also state the importance of students’ developing discussion and presentation skills.

Thornbury (2005) believes that when learners gain control over their own learning, they become more confident and develop a capacity to self-regulate their performance, and as a result they may become skilled autonomous performers. He also states that performances under quasi-authentic conditions, for example, with regards to urgency, unpredictability and spontaneity, help boost learners’ confidence and thereby also their development of autonomous language use. He adds that the following conditions for speaking tasks should be met in order to optimise this development:

- Language production needs to be maximised.

- Activities should be purposeful, i.e. with clear outcomes.

- Tasks need to be interactive so learners can notice how their utterances affect others.

- The level of the language and tasks need to provide a challenge to be overcome by learners.

- Learners need to feel safe and secure as and when they do speaking tasks; therefore, a supportive environment is important.

Furthermore, Thornbury (ibid) mentions that feedback on accuracy may be needed, or wanted, by some learners, even if the tasks are mainly for fluency practice. He suggests that error corrections can be done in a non-obtrusive way, either after the task is completed or as “repair” and mainly for clarification when mistakes concerning the meaning of words or concepts occur.

Autonomous Learning and Support for Speaking Practice at CPIT

The steps taken to enable autonomous learning development at CPIT include classes being scheduled for one hour of self-study time each week during which Learning Facilitators (LFs) are available to guide students in the LSAC. One of the most important LF tasks, on these occasions, is to encourage students to actively take control of their own learning. To this end, students can also make use of some in-house Autonomous Language Learning (ALL) Guides and Individual Learning Plans (Dofs, 2011). The LFs assist students with planning, goal-setting, and choosing tasks to focus on. They also help learners find suitable resources, both on-line and from the vast number of ready-made adapted resources that the self-access centre holds (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2. A Student Takes Advantage of One of the Listening Posts Provided

Moreover, teachers help raise students’ self-awareness about their learning by integrating specific learner training tasks into the language lessons, along the same lines as those suggested in the ALL Guides. The aim is to assist students’ understanding of how to become more autonomous. Thus, training includes student participation in developing transferable skills and strategies for learning, so that they can take on more control and responsibility for their studies, particularly in an out-of-class environment.

This is based on Crabbe’s (1999, p. 449) suggestions about giving explicit instructions, when setting tasks in the classroom, to allow for knowledge transfer to self-study situations. In addition, students are also encouraged to share with their peers in class time any examples of good practice which they have found to be effective in their self-directed studies (Brown, 2002 p. viii). In order to bridge the gap between the two study situations, of classroom and self-access centre, this happens just after or before their weekly hour in the self-access centre.

Many students do want to take the opportunity to practise speaking during these self-study sessions and they therefore actively ask for it on their planning sheets. One reason for this preference is that they have not had much speaking practice in their own country, but also they seem to recognise that there is a chance of receiving assistance with this particular skill in a ‘non-threatening’ environment, with their peers.

Figure 3. The LSAC at CPIT – Examples of Both Modern and More Conservative

Study Spaces

Once students have experienced the difference between being more active in the LSAC and being more passive in the classroom, many begin to realise that they learn better when they actively take responsibility for their own learning and language practice (Dofs, 2007).

The Speaking Corner at CPIT

When the LSAC was refurbished, in 2008, a conscious choice was made to divide the room up into skills-based learning areas, i.e., for reading, writing, listening and speaking skills, and then with the language systems, i.e., grammar and vocabulary, in the middle, feeding into the skills. This new layout was specifically designed to provide for variations in individuals’ preferred learning styles; for example, offering alternatives between private or group studies, between relaxed or more conventional seating, and between modern or more conservative study areas.

At the outset, the aim was to create a soundproof speaking corner; however, that was not possible within the budget, so the decision was made to make the most of what had been allocated. Today, two screens provided by sets of shelves, define the speaking area in the far corner of the LSAC, so albeit not sound proof it allows for a reasonably discrete, private, and designated space for making speaking ‘noises’. It is furnished in such a way as to suit individuals, pairs, or small groups of up to four students at a time. There is a small table with a CD player on it and a recording device, a couple of upright chairs, and a couple of comfortable ones (see Figure 3).

In order to make the speaking corner work for authentic speaking practice, the space was also equipped adequately with supportive resources, on the shelves, walls, and divider screens, that students can easily access and make use of without any help. The resources include books, recordings, activities with clear instructions, pronunciation charts, an overview of useful speaking strategies, a self-assessment chart from the European Language Portfolio, and card games as prompts for pair or group practice; however, students often need an introduction, as well as some encouragement, to make good use of these resources. Such needs are dealt with by the Learning Facilitators (LFs), according to students’ learning intentions for any of the skills, by looking at the tick box section, included for this purpose, on the learners’ planning sheets. If more students than one have indicated a need for speaking practice, then the LFs group them together and they show them how certain resources can be utilised (see Figure 5).

This development of speaking support is very much a work-in-progress being modified and adapted as new ideas and experiences unfold. The LFs participate in formalised observations of each other over the year and they keep a reflection diary which then forms the basis of regular development discussions between LSAC staff members around how to give the best possible assistance to students.

Analysis of Activities and Resources

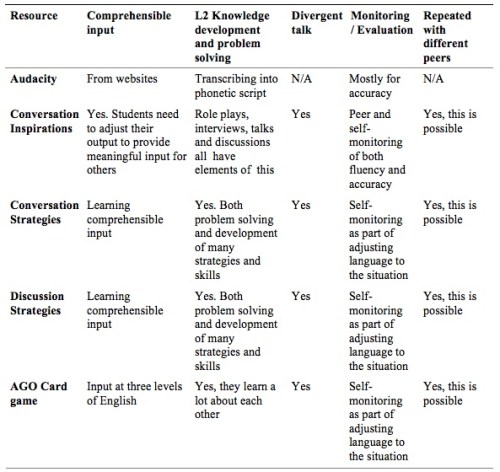

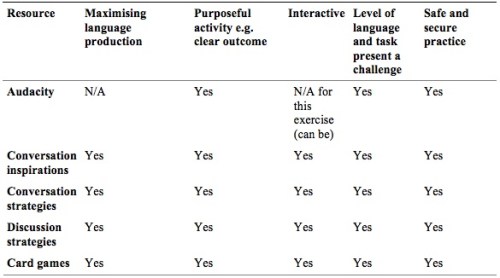

To understand more about the usefulness of the activities and resources provided in the LSAC today, a selection of resources are analysed (in Tables 1 and 2) for their contribution to enabling comprehensible output and helping develop the capacity to self-regulate and improve autonomous language use (Anderson, Maclean & Lynch, 2004; Thornbury, 2005). These resources include Audacity – a sound recording application, Conversation Inspirations by Zelman (2009), Conversation Strategies by Kehe and Kehe (2008), Discussion Strategies by Kehe and Kehe (2007), and a question and action card game named AGO by Butchers (2011). Reflections on the perceived usefulness of these materials in the LSAC are included in the overall analysis.

Table 1. Overview of Resources and the Task Design Principles

Table 2. Overview of Resources for Optimising Autonomous Performance Development

The resources and activities are described in more detail below, along with reflection on their ability to enable comprehensible output and the capacity to self-regulate.

Audacity

This free downloadable recording device from the internet, http://audacity.sourceforge.net/ has been very useful for students who wish to check their pronunciation and to practise speaking accuracy. One activity suitable for Audacity suggested in the LSAC is that students:

- Open up a web site with an audio source, for example, http://www.elllo.org/

- Listen to the text as many times as they need to in order to understand the gist

- Click on the transcript and listen and read at the same time

- Work with unknown vocabulary

- Copy the text into this vocabulary highlighter, http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/alzsh3/acvocab/awlhighlighter.htm in order to see which of the words in the text are in the Academic Word List (AWL) produced by Coxhead (2000)

- Listen and repeat after … which is shadow listening/speaking

- Record themselves when reading the same text aloud

- Compare with the original sound file

In this way Audacity is mainly being used for individual pronunciation practice and accuracy performance. Students are also encouraged to self-assess their accuracy by transcribing one part of their own recording into phonemic script, exactly the way they hear the sound, and then checking this with a dictionary. This activity offers a useful challenge as well as knowledge development. The whole activity is purposeful, with the clear outcome of improving pronunciation. Moreover, following the suggested order and techniques above gives students more confidence as they work through the activity, e.g. listening many times and learning unknown vocabulary before making an attempt to speak results in more certainty. Audacity can, of course, also be utilised for pair and small group recordings and then be used with different students each time: however, that is not covered in this analysis.

Conversation Strategies and Discussion Strategies

Targeted learning of strategies and skills for holding conversations and discussions is encouraged by providing activities for practice of these life-like speaking situations. As many EAL students have limited speaking experience, particularly in using these techniques, the speaking corner is equipped with some self-study exercises on this topic from the books, Conversation Strategies and Discussion Strategies by Kehe & Kehe (2007; 2008). These resources take learners through a whole set of useful activities which develop strategic conversation and discussion skills. They contain examples and activities on how to: begin a conversation, clarify something, interrupt someone, elicit information, repair conversations, end conversations, gossip, explain something, etc. Students typically work in pairs or small groups. Through their interactions, students get comprehensible input and they also have to adjust their output in order to provide meaningful input for other students. Moreover, these activities are meaningful in that they provide students both with knowledge and with accuracy practice which are useful for later interactions with more authentic exercises for fluency. Some of the exercises are information-gap type activities so they require divergent talk and skills to deal with unpredictability, thereby offering development of problem-solving skills and L2 knowledge while presenting a suitable challenge at an appropriate level of English. An immediate, but perhaps unconscious, self-monitoring (Dickinson, 1987) would occur as and when they work through these activities, because they need to make themselves understood and therefore they adjust their language accordingly. These cards also help maximise language production, as knowledge will ultimately be transferred to other practice, or real-life, situations.

Conversation Inspirations

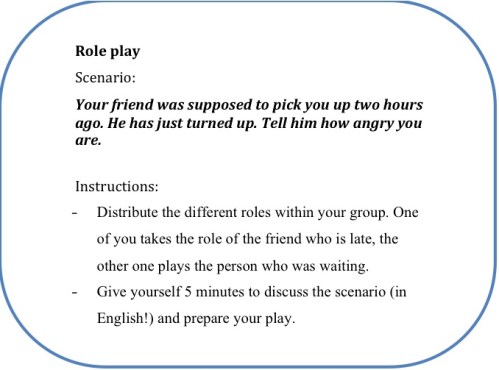

The Conversation Inspirations resource by Zelman (2009) provides opportunities to simulate authentic interactions and is mainly for fluency practice. The activities have been grouped into five different themes: Role Plays, Interviews, Talks, Stories, and Discussions. Students do the activities in groups of two or three choosing a card and following the instructions (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. An Example of a Role Play Card

In doing the activities, students gain a whole range of useful near-life speaking experiences; they practice divergent talk, solve language problems, and adjust their output to suit the unpredictability, urgency and spontaneity of the interactions. Furthermore, the Role Plays especially have provided an inspiring and non-threatening activity for many students, as they tend to be less embarrassed by making mistakes when they take on a role than when they have to produce authentic language. Student outcome from this activity relate mostly to fluency; however, students are encouraged to reflect and make notes of any questions and language problems, and to discuss these with LFs or the teacher after the activity. This facilitates development of accuracy and at the same time encourages students to take responsibility for their own progress.

Card games

Card games are used as prompts for some speaking activities. The LSAC has recently invested in all three levels of the question and action card games AGO by Butchers (2011). The questions on these cards range between easier ones, with one- or three-word questions for beginners, to longer ones with more difficult language up to an intermediate level of English. There are pictures to help with answers for the easier cards and both pictures and texts for the higher levels. The questions generate a lot of talking and students develop confidence in their speaking skills as they take part in the interactions, based on their own experiences. The cards also give students the opportunity to get to know each other therefore this creates a less threatening environment for speaking and sharing ideas. The main aim is to practise fluency in speaking and evaluation is not encouraged, however, LFs are always available should students want some clarification or feedback on their performance.

Figure 5. An LF with a Student in the Speaking Corner, Demonstrating a Card Game

The cards can be used over and over again with different speaking partners and as students become more confident they can use the more difficult question cards. While some students appreciate using these cards and use them repeatedly, others need more encouragement and reminders to make the best use of them.

Conclusions

The analysis described above, i.e. comparing other authors’ theories and ideas concerning learning outcomes with the activities and resources provided in our LSAC, generated very useful information and knowledge about the efficacy of current support, as well as highlighted areas where more or better support is needed. The analysis of this small selection of speaking activities shows that they meet almost all of the conditions for optimising autonomous performance development as outlined by Thornbury (2005), as well as the task design principles needed to push for comprehensible outputs, as suggested by Anderson, Maclean & Lynch (2004). The learners in the School of English at CPIT are most likely to improve their autonomous speaking skills, and they also learn more about how to self-monitor when they engage in these activities.

There are, of course, many other theories and criteria that could be utilised for a similar type of analysis; nevertheless, it is hoped that others working in the field of learner autonomy and language learning will find the process undertaken in this study of use and worthy of replication in their own teaching/learning contexts. This method can thus be recommended to anyone who would like to give speaking practice in a self-study situation a better chance.

Notes on the contributor

Kerstin Dofs came from Sweden to New Zealand 13 years ago. Her qualifications include a BA in Education, a Certificate in English Language Teaching to Adults (CELTA) and an MA in Language Learning and Technology, through the University of Hull in the UK. She has worked at CPIT in Christchurch for 11 years, as a lecturer in the School of English and for several years as a Senior Academic Staff member and the Manager of the Language Self-Access Centre for the Department of Humanities.

References

Anderson, K., Maclean J., & Lynch T. (2004). Study speaking. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, H. D. (2002). Strategies for success: A practical guide to learning English. New York, NY: Pearson Education.

Butchers, L. (2011). AGO card game. Kobe, Japan: AGO.

Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word list. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2), 213-238. doi:10.2307/3587951

Crabbe, D. (1993). Fostering autonomy from within the classroom: The teacher’s responsibility. System 21(4), 443-452. doi:10.1016/0346-251X(93)90056-M

Dickinson, L. (1992). Learner autonomy, 2: Learner training for language learning. Dublin, Ireland: Authentik.

Dofs, K. (2007, October). Helping language learners to greater independence – What works? In Carroll, M., Castillo, D., Cooker, L., & Irie, K. (Eds.). Proceedings of the Independent Learning Association 2007 Japan Conference: Exploring theory, enhancing practice: Autonomy across the disciplines. Kanda University of International Studies, Chiba, Japan. Retrieved from http://www.independentlearning.org/uploads/100836/ILA2007_008.pdf

Dofs, K. (2011). Encouraging autonomous language learning through classroom and language self-access centre initiatives (Unpublished master’s thesis). The University of Hull, UK.

Dofs, K., & Hobbs, M. (2011). Guidelines for maximising student use of independent learning centres: Support for ESOL learners. Christchurch, New Zealand: Ako Aotearoa. Retrieved from http://akoaotearoa.ac.nz/download/ng/file/group-7/guidelines-for-maximising-student-use-of-independent-learning-centres.pdf

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kehe, D., & Kehe, P. D. (2007). Discussion strategies. Brattleboro, VT: Pro Lingua Associates.

Kehe, D., & Kehe, P. D. (2008). Conversation strategies. Brattleboro, VT: Pro Lingua Associates.

Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. Oxford, UK: Pergamon.

Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensive input and comprehensible output in its development. In S. Gass and C. Madden (Eds.), Input in second language acquisition (pp. 235-253). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Thornbury, S. (2005). Teach speaking. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Zelman, N.E. (2009). Conversation inspirations. Brattleboro, VT: Pro Lingua Associates.