Kent Rhoads, University of Shizuoka, Japan

Jonathan deHaan, University of Shizuoka, Japan

Rhoads, K., & deHaan, J. (2013). Enhancing student self-study attitude and activity with motivational techniques. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(3), 175-195.

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

Research has shown that students will exhibit a positive attitude towards self-study, but that they will often fail to complete self-study activities. The purpose of this paper is to investigate positive instructor interactions and motivation of students to complete self-study activities and students’ attitudes towards self-study. Six English instructors at the University of Shizuoka created a one-semester self-access study log for use in the university self-access language laboratory in order to find out how many students would complete the log. One of the six instructors applied motivational techniques in the classroom in an effort to engender greater student self-study. Later a questionnaire was administered to 465 student participants to determine their self-study attitudes and activities. The data collected from the questionnaire and the high participation in the self-study activities suggest the positive impact the motivational actions employed by the instructor had on his students’ attitudes towards self-study activities. .

Keywords: Japanese university, self-access learning, motivation, attitude, self-study

It is known that students are attracted to self-study learning activities, but to what degree? Lai and Gardner (2007) describe a “gap between theoretical support and motivation to complete activities” (p. 199). Further, Kimura (2007) states there are “significant differences in motivation among students towards autonomous learning” (p. 77). Can positive teacher interaction provide enough influence to bridge the gap between theoretical and actual support and resolve the differences among students towards self learning? Gillies (2007) reports that “motivation precedes autonomy” (p. 130), while Ikeda and Takeuchi (2007) state “creating amicable instructor-facilitated sessions can be key for enhancing learners motivation for independent learning” (p. 112). Further, Lee and Yamaguchi Johnson (2007) argue “teachers have an important role in supporting students in their learning process” (p. 223). If teachers can motivate students for greater acceptance and use of self-study, then by how much, and what techniques are effective? Lai (2007) points out that “a majority of research in the English language learning field has been focusing largely on teaching or course effectiveness, but little has been done to look at what makes learners become self-determined enough to take control of their own learning, and the factors that differentiate successful and less successful self-access users” (p. 7). The purpose of this study was to further the findings in this field by attempting to examine the effect that teacher motivational techniques have on students’ attitudes towards their self-access study.

Scope of the Project

A formal research study was not initially planned, but instead the idea for a project developed as the primary researcher (one of the authors) tested different motivational techniques in his classroom in order to encourage self-study and questions from the students. Questions were later developed to help guide the analysis presented in this paper. As a result the project became an examination of which motivational techniques were found to be effective in the researcher’s classroom. The researcher was operating broadly within an action research paradigm and could draw upon the findings to further improve his practice.

The University of Shizuoka Self Access Language Laboratory

The University of Shizuoka opened its Self Access Language Laboratory (SALL) in April 2007. The one-room facility features thirty-six personal computers for individual student use, over 500 movie titles in DVD format and an area consisting of three sofas and one table for reading and conversation activities. Other printed media consist of The Japan Times, TOEIC preparation textbooks published by ETS, grammar textbooks, novels, manga (Japanese comic books) and National Geographic readers. From the beginning student usage of the SALL was low and disappointing to the university administration. Thus, it was decided that the teaching staff should determine ways to increase the number of student users.

In September 2009 the six Language Communication Resource Center (LCRC) instructors plus the Assistant Director of the LCRC (co-author of the paper) held a meeting that included a brainstorming session with the purpose of engendering more student use of the SALL. It was decided that a Self Access Study Log or SASL (Appendix A) should be created and distributed to the students in all oral communication classes during the second semester (beginning October 2009). The group decided that completion of the log would consist of doing ten online self-study exercises, as well as watching one movie and writing an information sheet about it. For this they would receive 10% extra credit toward their English grade. Each online self-study exercise should have a duration of not less than twenty minutes in order to receive credit. The students’ activity would be monitored by the SALL staff, such that when an exercise was completed the staff would place one stamp on the sheet. It would be decided by each individual instructor how to apply the extra credit to the students’ final grade. To make it easy for the students to find appropriate online self-study exercises, a comprehensive list of links to e-learning websites was compiled by the six instructors and posted on the university web site. This list was set to automatically display on all SALL computers whenever an Internet browser was opened. (Please view the page at http://langcom.u-shizuoka-ken.ac.jp/links.) The students would be allowed to choose their own study exercises from the list provided. The deadline for completion was up to the individual instructor, but the final date would be before final exams in February 2010. Following the deadline, the study logs were collected and counted by the instructors. Students were then asked to complete a follow up questionnaire to find out why they did or did not complete the SASL. Included were questions about their self-study activities and attitudes.

Description of the Project and Report on the Results

This paper investigates the following questions:

- What uptake rates of SASL by students were observed?

- What effect (if any) did the introduction of motivational techniques have on students’ attitudes to self-study?

- What effect (if any) did the introduction of motivational techniques have on the types of activities that students engaged in?

The description will be presented in two parts:

Part One is a discussion of the motivational techniques applied in the researcher’s classes to encourage his students to complete their SASL. Also included is an inventory of the number of completed SASL sheets returned by the students to each instructor.

Part Two is a discussion of a questionnaire created to determine student attitudes about using the SALL and a report of the results. The students completed the questionnaire at the end of the school term in February 2010. It included two parts. The first part was meant to find out why the students who completed the SASL did so. The second part asked the students about their self-study activities. The main focus of the paper is the students’ attitudes and whether they were influenced by teacher motivational techniques.

Part One: Self Access Study Log Sheets Results

Motivational techniques adopted by the instructor

The authors are unable to confirm what the other instructors did in terms of motivating and encouraging their students to use the SASL, but this is an account of the actions of Instructor Number Six (principal author of the paper). Instructor Number Six handed out the SASL and independently decided to use six motivational techniques in his classroom. The main reason he took these steps was because he recognized that the university administration had been disappointed in student usage of the SALL and felt it was an integral part of his employment to provide motivational techniques and incentives beyond simply handing the SASL to his students and ordering them to complete it. From his previous ten years of experience teaching similar students at the University of Shizuoka, the instructor determined that motivation in the classroom would be necessary for a greater number of students to complete their self-study. Thus, he gave considerable thought to which motivational techniques would be most effective. Previous piloting of motivational techniques led the instructor to choose six motivational tools. They are as follows:

1) Prior to receiving the SASL, all oral communication students would be taken to the SALL in order to introduce them to the facility and encourage them to make use of it.

Barrs (2010) states this about orientating students to the SALL (his terminology is SASC), “in order for students to make appropriate use of SAC facilities, it is crucial that they know and understand what is available and how to use it. In my opinion, there should be a comprehensive orientation programme in place whereby students are introduced to what is on offer and guided in the use of the resources and equipment” (p. 13). McMurray, Tanner and Anderson (2009, Conclusions, Implications and Suggestions Section) found much the same in reporting that, “students who were well oriented were more frequent visitors to the SASC as well. We now know that the orientation has a strong effect on how the students use the SASC.”

2) Upon receiving the SASL at the beginning of the second semester, students would once again be taken to the SALL and shown how to complete an exercise, do a log entry, and have their sheet stamped by the SALL staff.

3) A “Self Study Instruction Sheet” would be distributed as a reference for students on how to complete their SASL. This document (Appendix B) also includes motivational messages.

4) Throughout the semester, both in the classroom and in the SALL, students would be encouraged to complete the log. Those who finished early would be praised in front of other students.

Lai reports the following about student self-study activities over a period of time and how instructor encouragement over time can be positive. “They reported that their passion for SALL diminished as the semester progressed. The lack of perseverance was an inhibiting factor for learners who were initially motivated ” (p. 69). This suggests that the initial excitement and motivation that students feel about using the SALL wears off as they become more involved in other university studies and activities and that instructor encouragement over a period of one semester or longer can produce positive effects.

5) Students would be regularly reminded of the deadline to complete the log.

6) Students would be incentivized to complete the log with 10% extra credit. It would also be made clear that completion of the SASL was voluntary and that final grades would not be lowered should students decide not to do so.

Further Lai informs that students expect to be actively and positively directed by their teacher to remain motivated to continue to study in the SALL, “instead of working in partnership with teachers, the learners expected teachers to play more directive roles in language learning and the absence of such roles would result in a lack of motivation” (p. 74).

Number of completed Self Access Study Logs returned to the instructors

Instructor Number Six distributed 226 logs of which 215 (95%) were completed. This was substantially higher than the completion rate of students in other classes. For example, Instructors Number One and Two collected no completed log sheets; Instructor Number Three collected 18 completed logs. (A completion percentage cannot be reported because it is not known how many log sheets Instructor Number Three originally distributed.) Instructor Number Four handed out 142 logs of which 97 (68%) were completed. Data for Instructor Number Five was incomplete. The high completion rate of logs by students taught by Instructor Number Six is likely to be due to the motivational techniques employed.

Part Two: Follow-Up Questionnaire Results-Attitude and Activity

This section is a discussion of the three-part questionnaire administered to students and a report of its results. The principal researcher and the Assistant Director of the LCRC created a follow-up questionnaire to determine student activity and attitude about using the SALL at the end of the second academic semester in February 2010. The first page of the online questionnaire (using SurveyMonkey.com) prompted the students to select whether they did or did not complete the SASL. Making this choice directed the students to one of two different questionnaires. The third part of the questionnaire asked the students about their self-study activities. All students, regardless of whether they completed the SASL or not, completed the third part. Instructors Two, Three, Four and Five administered the electronic survey to their students. Instructor Number Six made paper copies of the online questionnaire and had his students complete it anonymously outside of class during the second and third weeks of February 2010.

Respondents taught by Instructors Two, Three, Four and Five will be referred to as “Low Interaction Group” (LIG) as these students are assumed to have interacted least with the SASL. Respondents taught by Instructor Number Six will be referred to as the “High Interaction Group” (HIG) as these students had high interaction with the SASL. It is useful to separate the respondents into two groups (LIG and HIG) in order to make observations about the effect, if any, of the motivational interventions employed by Instructor Number Six on SASL completion rates and self-study attitudes.

Questionnaire Completion Rate Results

As previously stated, the following results focus on those portions of the questionnaire regarding student attitude and activity about completing the SASL and how they were impacted by instructor motivational techniques.

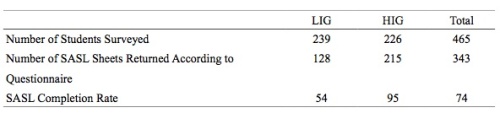

A total of 239 LIG students filled out the online questionnaire. 128 of the 239 LIG students completed the SASL, a SASL completion rate of 54%. The total number of students who stated they completed the SASL (128) compared to the total number of SASL sheets actually returned to instructors (115) is a difference of 13. The reason for this discrepancy is unknown. A total of 226 HIG students filled out the questionnaire. 215 of the HIG students completed the SASL, a SASL completion rate of 95 percent (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of SASL Completion Rates

Questionnaire Results and Discussion

The first part of the questionnaire results will deal with the attitude of the students who completed the SASL. The questionnaire was composed of eight questions. Each question was to be marked by choosing one of the following:

1 = Very unimportant/untrue

2 = Somewhat unimportant/ untrue

3 = Somewhat important/true

4 = Very important/true

These were the directions for the respondents to follow in order to complete the questionnaire: Choose 1, 2, 3, or 4 for each question below. Why did you complete the Self Access Study Log? Which reasons or factors were important or true for you?

The following results are represented as percentages.

Question Number One

Table 2. Question Number One: “The 10% extra credit I received for completion was worth my time and effort.”

A greater number of HIG respondents answered this question more favorably, especially the “Somewhat important/true” response. This shows that the students responded favorably to extra credit being given by their instructor in their oral communication course for completion of self-access study when motivated by the instructor interaction. Lai (2007) reported similar findings, “Positive reinforcement can take the form of bonus marks in the case of SALL being a component of a course” (p. 88).

Question Number Two

Table 3. Question Number Two: “It was a positive experience to study on my own.”

A large percentage of respondents from both groups answered this question positively, but the HIG slightly more so. Once again positive reinforcement from the instructor appeared to affect the students’ attitudes towards self-study. The findings from this question replicate those of Lai (2007) which report, “The pleasurable feelings associated with performing tasks that the learners found interesting was one of the major sources of motivation for them to carry on with their SALL plan” (p. 57). These findings suggest that once students are properly orientated to the SALL and given encouragement and incentive to use it, a large portion of them will view using it in a positive and pleasurable way.

Question Number Three

Table 4. Question Number Three: “I discovered a new way to learn.”

A larger percentage of those students (the HIG) who completed the SASL responded “Very important/true” to this question. Their introduction to the SALL and specific instructions on how to complete the SASL by Instructor Number Six could have been a strong influence for the more positive response by the HIG. Being introduced to the SALL in a positive manner reinforced their attitude about discovering a new way to study in a pleasurable way. Lai (2007) reports that “Being stimulated by the pleasurable feelings derived from the discovery of new knowledge in English, those learners would be more motivated to sharpen their English skills in order to explore the subject matter further ” (p. 59). An attitude of discovering a new way to learn and greater motivation to do so are linked.

Question Number Four

Table 5. Question Number Four: “I felt pressure to keep up with the other students in the class by completing the log.”

Feeling pressure was less of a factor for the students to complete the SASL than the other motivational tools employed by the researcher. However, the HIG responded more positively to the feeling, and importantly did not respond negatively to the feeling. The students felt little negative pressure, but were exposed to the positive motivational links of using the SALL and their classroom learning. As pointed out by Cotterall and Reinders (2001), “forcing students to use self-learning facilities may de-motivate them to learn independently, but it is important to establish links between what happens in the class and what is available outside (and how to use it) in order for the students to begin taking independence in their learning” (p. 6). Similarly, Lai (2007) found that the SALL users did not view the activity of other students in the classroom as a form of pressure, “despite the seemingly important role that peers play in course-based SALL as suggested by the data from the focus groups and written evaluations, most learners in this study did not see peers as the most important ‘significant others’ ” (p. 72).

Question Number Five

Table 6. Question Number Five: “I feel self-study in the SALL is an important part of learning.”

Cotterall and Reinders’ (2001) data suggests a relationship between learners’ positive attitudes about self-study usage and actual visits to centers. All the respondents in this study exhibited a very highly favorable attitude about using the SALL, but more so for the HIG. As a result the HIG students, who had more highly favorable attitude, used the SALL far more often than the LIG students, which confirms the previous findings by Cotterall and Reinders.

The second part of the questionnaire asked the students about their self-study activities. The questionnaire offered the students a list of 18 different self-study activities and asked the question:

How did you study English on your own this semester? Circle all the activities you did.

Listening: Watched movies

Listening: Watched You-Tube

Listening: Watched television

Listening: Listened to music

Listening: Listened to podcasts

Reading: Read print news

Reading: Read online news

Reading; Read books

Reading: Read comics

Reading: Read magazines

Speaking: Talked with Japanese friends in English

Speaking: Talked with native English speakers

Speaking: Talked with the university native English speaking instructors

Writing: Kept a dairy

Writing: Wrote on the Internet sites (e.g., Facebook, Mixi) in English

Studied for a test (e.g., TOEIC, Eiken)

Studied grammar

Studied vocabulary

Did you do any other activities not listed above? Please write them below.

The researchers found that the type of outside-class self-study activities that students engaged in did not vary between the LIG and the HIG.

Discussion

It appeared that the motivational techniques applied by Instructor Number Six had a positive impact on the students desire to complete and return the SASL by the fact that 95 percent of his students did so. A positive atmosphere created by the instructor towards motivating students to complete and return self-access study sheets can help achieve a successful completion rate. As Benson (2001) explains, “any practice that encourages and enables learners to take greater control of any aspect of their learning can be considered a means of promoting autonomy” (p. 109). Kimura (2007) states “teachers play a crucial role in the development of autonomous language learning behaviour” (p. 7).

In addition, the questionnaire responses indicated that the students – particularly those in the HIG group – had a positive experience with the self-study activities, suggesting that the motivational actions were effective.

One final point is that student self-study activities did not seem to vary greatly no matter how well they were motivated to study outside the classroom.

Conclusion

In 2007 Lai produced the first in depth study of how teacher interaction with and motivation of students can affect their self-study habits. To a large degree the findings of this project are in agreement with those of Lai, with the following results in common:

1) Students will react positively when given extra credit for self-study outside the classroom.

2) Students feel positive about self-study outside the classroom when their teacher provides motivational tools.

3) Students have a positive feeling about discovering a new way of learning when their teacher interacts with them regarding self-study outside the classroom.

4) Students do not feel pressure from other students in a negative way to participate in self-study activities outside the classroom.

Although based on limited data, the results of this project suggest that the six motivational practices employed by the instructor contributed to an enhancement of attitudes toward self-study and resulted in greater rates of SASL completion. The results also indicate that while teacher interaction and motivation play positive roles in students’ attitudes toward self-access learning, they make little difference in the type of self-study activities students pursue. The results also suggest that students typically begin with a positive attitude towards self-study in the SALL, but this positive attitude becomes even stronger when their instructor motivates them to study outside the classroom on their own.

Recommendations

The authors recommend that, in contexts where self-access resources exist, instructors involved in second language acquisition should actively use the following six positive motivational techniques on their students to encourage greater engagement with self-study:

1) On the first day of class introduce new students to self-access study facilities and encourage them make use of them.

2) Demonstrate to the students how to complete an online self-study activity and what steps to take to receive proper teacher credit for it.

3) Create and hand out to the students an instructional sheet of step number two so they can use it as a reference. Also include motivational messages on the sheet.

4) Encourage the students in class to do more self-access study and praise those who finish activities early or do extra activities.

5) Continuously remind students of the deadline to complete an activity sheet.

6) Make it clear in a positive way to the students the benefits of self-access study, such as learning more English or achieving a better class grade.

Clearly this project has several limitations from the standpoint of a research project. For example, it was not clear what was occurring in the other classrooms and making comparisons between LIG and HIG is problematic. In addition, the principle researcher gathered data from participants in his own classroom. Lai (2007) encountered the same limitation and made this recommendation, “to replicate this study with another group of learners, one limitation of the research design of the current study needs to be overcome. The limitation derives from the fact that the researcher is also the teacher of the classes being studied” (p. 92). The researcher is in agreement with Lai and recommends that for future studies in this field, the researcher should not also be the research participants’ classroom teacher. This would mitigate any bias that may be involved with this interaction.

Epilogue

In March 2010 the researcher wrote a summary of the research project results and distributed it internally. The other five LCRC instructors then became more proactive in utilizing the six motivational tools recommended by the researcher during the academic year beginning April 2010. Completion of the SASL was also adopted by the six instructors as a 10 percent component of the students’ final grade for most oral communication classes. Usage of the SALL showed a dramatic increase beginning in October 2009 (one month after the project began) and remained high through the end of academic year 2010-2011. This is depicted in Appendix C (Table 1 and Figure 1). In Table 1 please note the sharp increase of student usage of the SALL beginning October 2009. The data presented in Appendix C largely validates the research results and the positive impact of using the researcher’s six motivational tools.

Notes on the contributors

Kent Rhoads (MBA Whittier College) has taught at the University of Shizuoka since April 1999. He is currently conducting research about student online vocabulary self-study with Quizlet.com and FreeRice.com. http://langcom.u-shizuoka-ken.ac.jp/rhoads

Jonathan deHaan (Ph.D. New York University) is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of International Relations at the University of Shizuoka, Japan. His main teaching and research interests are in the areas of educational games and simulations. Website: http://langcom.u-shizuoka-ken.ac.jp/dehaan

References

Barrs, K. (2010). What factors encourage high levels of student participation in a self-access centre? Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(1), 10-16. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun10/barrs/

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

Cotterall, S., & Reinders, H. (2001). Fortress or bridge? Learners’ perceptions and practice in self-access language learning. TESOLANZ, 8, 23-38. Retrieved http://www.hayo.nl/tesolanz.html

Gillies, H. E. (2007). SAL for Everyone?: Motivation & Demotivation in Self-Access Learning. Published abstracts from the 3rd Independent Learning Association 2007 Japan Conference: Exploring theory, enhancing practice: Autonomy across the disciplines, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan (p. 130). Chiba, Japan: Kanda University of International Studies.

Ikeda, M., & Takeuchi, Osamu. (2007). What can promote learners’ motivation for continuing CALL independently? Published abstracts from the 3rd Independent Learning Association 2007 Japan Conference: Exploring theory, enhancing practice: Autonomy across the disciplines, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan (p. 112). Chiba, Japan: Kanda University of International Studies.

Kimura, M. (2007). Development of autonomy in the language class in Japan. Published abstracts from the 3rd Independent Learning Association 2007 Japan Conference: Exploring theory, enhancing practice: Autonomy across the disciplines, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan (p. 77). Chiba, Japan: Kanda University of International Studies.

Lai, M. W. C. (2007). The influence of learner motivation on developing autonomous learning in an English-for-Specific-Purposes course. Master’s thesis, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. Asian EFL Journal. Retrieved from: http://www.asian-efl-journal.com/thesis_lai_conttia.pdf

Lai, M. W. C., & Gardner, D. (2007). The influence of learner motivation on developing autonomous learning. Published abstracts from the 3rd Independent Learning Association 2007 Japan Conference: Exploring theory, enhancing practice: Autonomy across the disciplines, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan (p. 199). Chiba, Japan: Kanda University of International Studies.

Lee, A. N., & Yamaguchi Johnson, T. (2007). The teacher’s role in developing students’ capacity for self-directed learning. Published abstracts from the 3rd Independent Learning Association 2007 Japan Conference: Exploring theory, enhancing practice: Autonomy across the disciplines, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan (p. 223). Chiba, Japan: Kanda University of International Studies.

McMurry, B.L, Tanner, M.W., & Anderson, N.J. (2009). Self-access centers: Maximizing learners’ access to center resources. TESL-EJ, 12(4). Retrieved from http://tesl-ej.org/ej48/a2.pdf